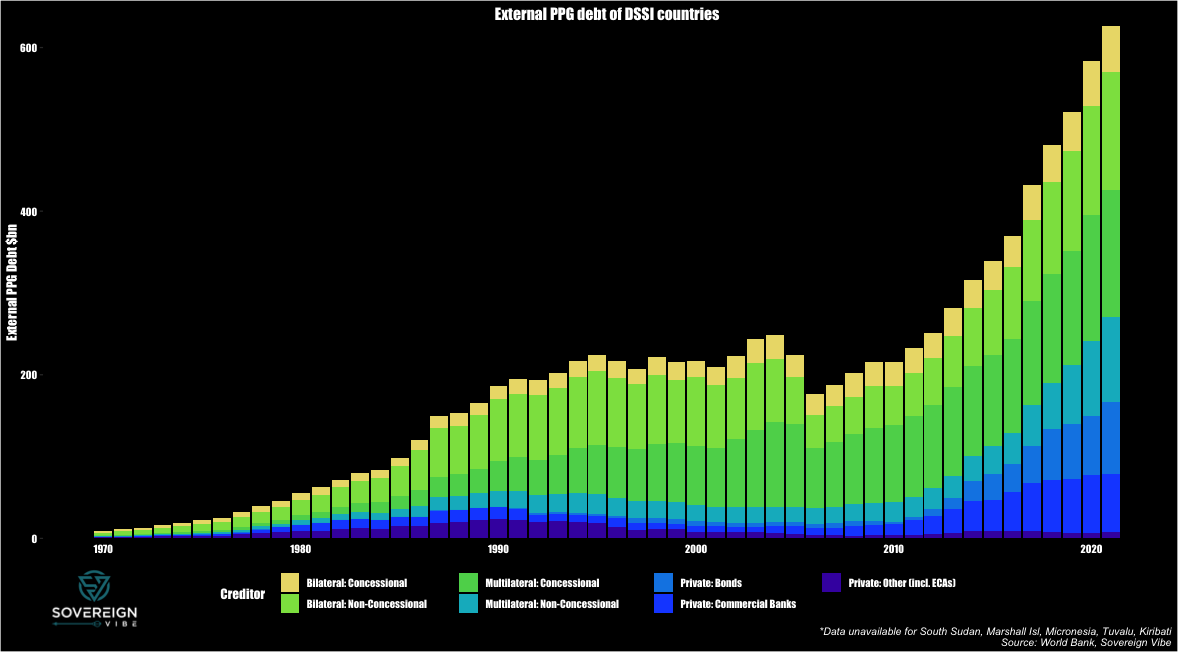

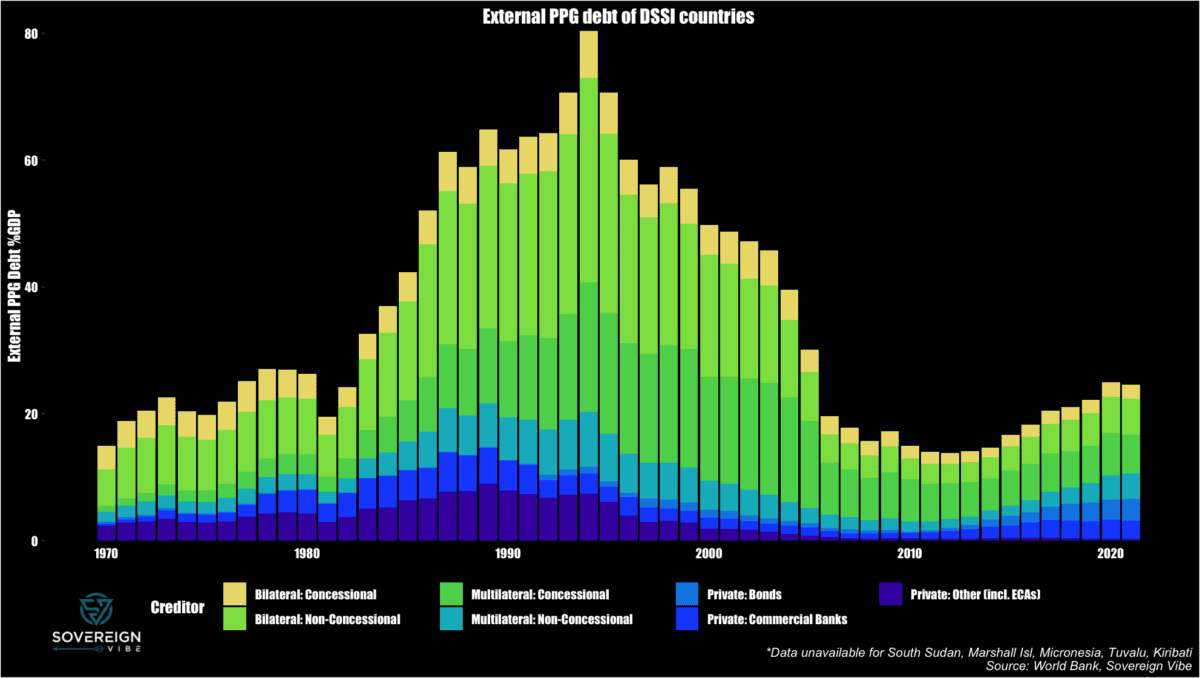

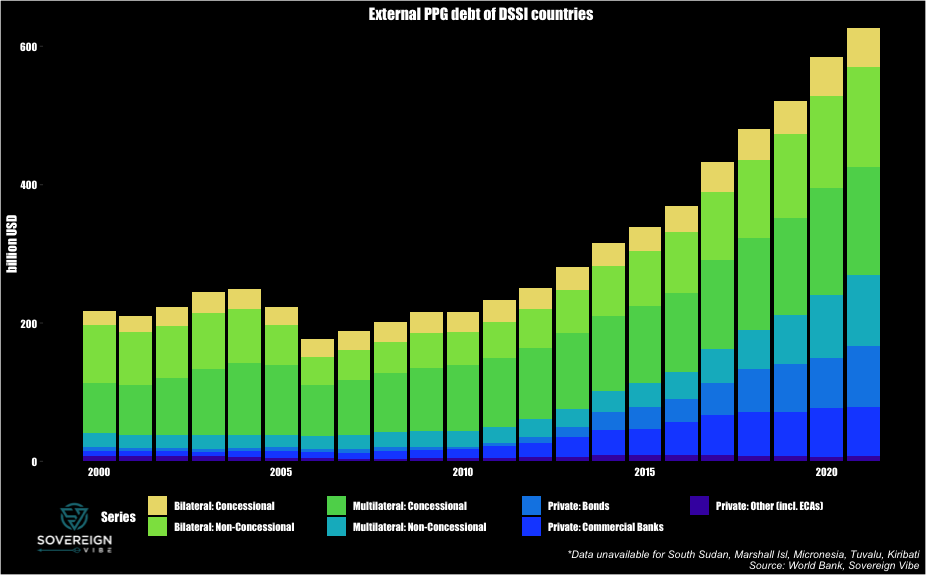

The first web application as part of Sovereign Vibe’s DataHub disaggregates the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics’ outstanding debt stock data for 68 low-income countries by creditors type: multilateral, bilateral, and private. Further decompositions are provided for the concessional and non-concessional components of multilateral and bilateral lending, and also for private credit by bondholders, banks, and other private lenders.

This first update to the “External Sovereign Debt: DSSI Countries” dashboard adds some helpful new features for users seeking to quickly view and analyze external public and publicly-guaranteed debt stock data. To begin with, the updated app now covers data extending back to 1970, the earliest year available in the WB database. The pilot version only extended coverage back to 2000, given the heavier data burden and the uncertainties around this initial attempt.

Secondly, this new version of the dashboard allows users to view the IDS debt stock data in US dollars, as previously, but now also includes an option to view the readings as a percentage of GDP.

Third, a new category has been created to aggregate all borrowing countries. When opening the application, the “Sovereign borrower(s)” category defaults to “All DSSI,” while the “Creditor(s)” menu defaults to “World” so that users can get a high-level view of all lending (i.e. from the entire world) for all these countries (i.e. all DSSI) at once. This view is presented in the previous post, “Cure worse than the disease,” but was previously unavailable through the dashboard.

Finally, the update enables users to select multiple creditors when viewing a country’s external debt stock. Over two hundred creditor locations and types are specified in the creditor menu, so, for example, a user could choose to look at how much China, France, bondholders, and the World Bank-IBRD have lent to Zambia up until the latest data reading.

Further updates to this dashboard could include allowing users to select multiple borrowers at once. While in practice providing this is currently possible for viewing the debt stock data in US dollars, some back-end work is needed to make aggregating borrowers usable in percentage of GDP. Next steps will include:

- Enabling users to select multiple borrowers at once

- Expanding coverage to the broader emerging markets universe

- Moving beyond external debt stocks and towards associated external sovereign debt flows

- Progressing from descriptive data towards analytical outputs

What are your thoughts on this basic dashboard? How do you think it could be improved, and what features would you like to see? Feel free to submit comments in the section below or via the website’s Contact page.

All suggestions for avenues of further research are welcome as Sovereign Vibe progresses from its current pilot phase towards deeper analysis of challenges facing the sovereign debt landscape and the emerging markets complex.