The past few weeks of political headlines have provided yet more confirmation of a long-term trend: the distinction between emerging and developed markets is less clear than it once was. Emerging and frontier markets are less politically stable, or so the old consensus goes.

Yet Emmanuel Macron has flown in the face of all that by dissolving France’s parliament and calling snap legislative elections. The prospects of extremist parties coming to power or of a hung parliament in France has sent European markets reeling.

Sadly, Macron’s folly is just the latest episode in a recent litany of rich-world self-sabotage. Cue January 6th, just about everything that Donald Trump does, Brexit, and the tenures of Boris Johnson and Liz Truss. To complement the Anglosphere’s masochism, add in the rise of the Italian far right, multi-faceted German despondence, and demographic reversals in Japan, Italy, and Germany. The result is something other than a pretty picture. At the recent G7 meeting in Italy, every leader save Prime Ministers Meloni and Kishida was speaking from a position of political weakness.

The upside-down global trading system

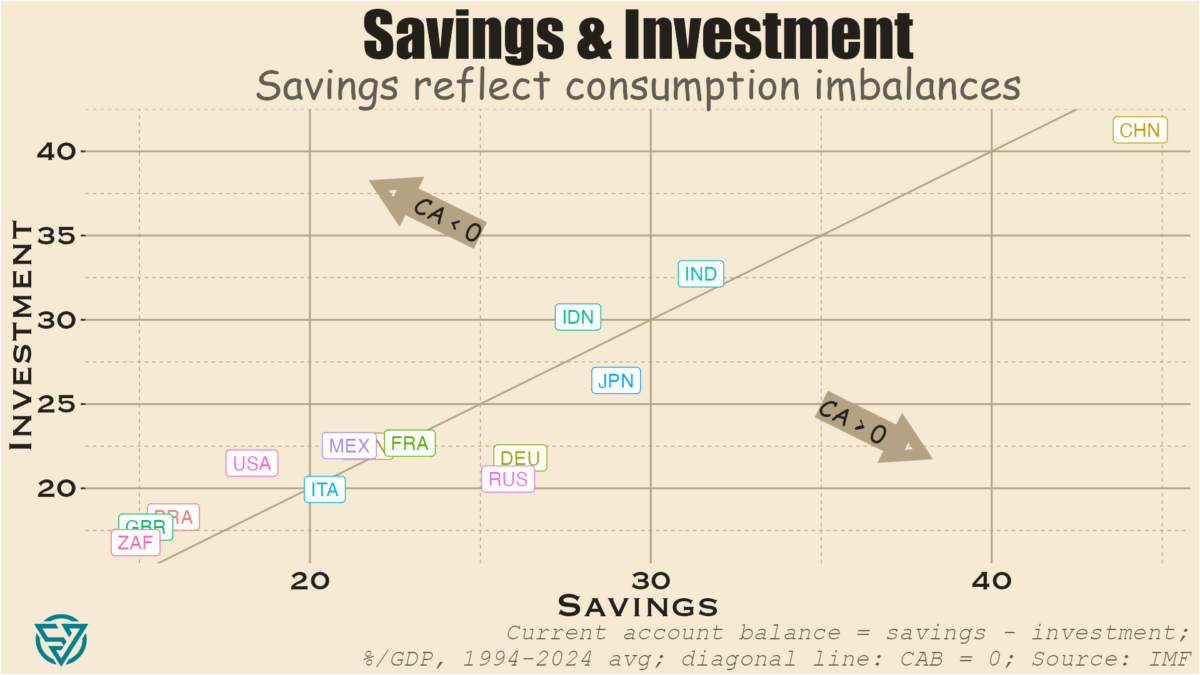

One of the driving forces behind this wealthy-country malaise is the absence of a well-functioning global trading system. Consider that savings is the difference between income and consumption. One would think then that advanced economies would have more savings than emerging economies, as they have greater income. Not so.

As a share of GDP, China, India, Indonesia, and sometimes Russia all have higher savings rates than G7 countries. In fact, only Germany and Japan have roughly equivalent savings rates, followed by Canada, France, and Italy. The US and the UK trail distantly.

The Chinese anomaly

The advantage of a high domestic savings rate is of course that a country can use these fund investments. China is an extreme example of this. By suppressing domestic consumption, Beijing has been able to jack up investment levels to dizzying heights without even running a current account deficit.

This is of course a significant problem because that abundance of savings ends up penalizing savers. The result is a vicious circle where the authorities discourage consumption in order to keep interest rates low for investment, which hurts people with money saved up in the bank. It’s a classic case of financial repression. Remember that the Chinese government directs a lot of investment from state-owned banks to inefficient state-owned enterprises. This is a recipe for slower growth, which China is currently experiencing.

These chronically high savings end up “exporting” China’s weak consumer demand to the rest of the world, to the dismay of its trading partners. Juicing up savings to such levels results in over-investment domestically, without which the world’s largest current account surplus in dollar terms would be even larger. Remember that investment most typically reflects fixed capital formation, e.g. the construction of infrastructure and real estate assets. Hence the ghost cities that pepper the real estate landscape. Echoing US residential real estate pre-2007, many Chinese families had bought several apartments as investments during the boom years and are now enduring the ongoing property crisis currently afflicting the country.

CAB deficit, low investment, high consumption

The US and the UK are the best counter-examples to the Chinese model. In these countries, consumption is subsidized, partly through easy access to a diverse array of credit products at relatively low rates. Higher consumption naturally results in lower savings rates, which in turn mean some combination of:

- Investment would have to decrease significantly for the current account to be at zero and/or

- If investment doesn’t decrease by a lot, then there must be a current account deficit.

In reality both countries experience both low investment and current account deficits. This combination isn’t only an obstacle for directing resources towards badly-needed infrastructure maintenance and upgrades. Current account deficits make it harder for capital to flow from rich countries to poor ones that need it.

What we have is a world where the US, the UK, and other wealthy countries over-consume. France, Canada, and Australia are mostly in this camp as well. Over-consumption, external deficits, and financialization don’t only come at the cost of infrastructure investment and funding for international development. They also result in the outsourcing of jobs and entire industries because subsidizing consumption comes at the expense of production.

Exorbitant privilege, exorbitant cost

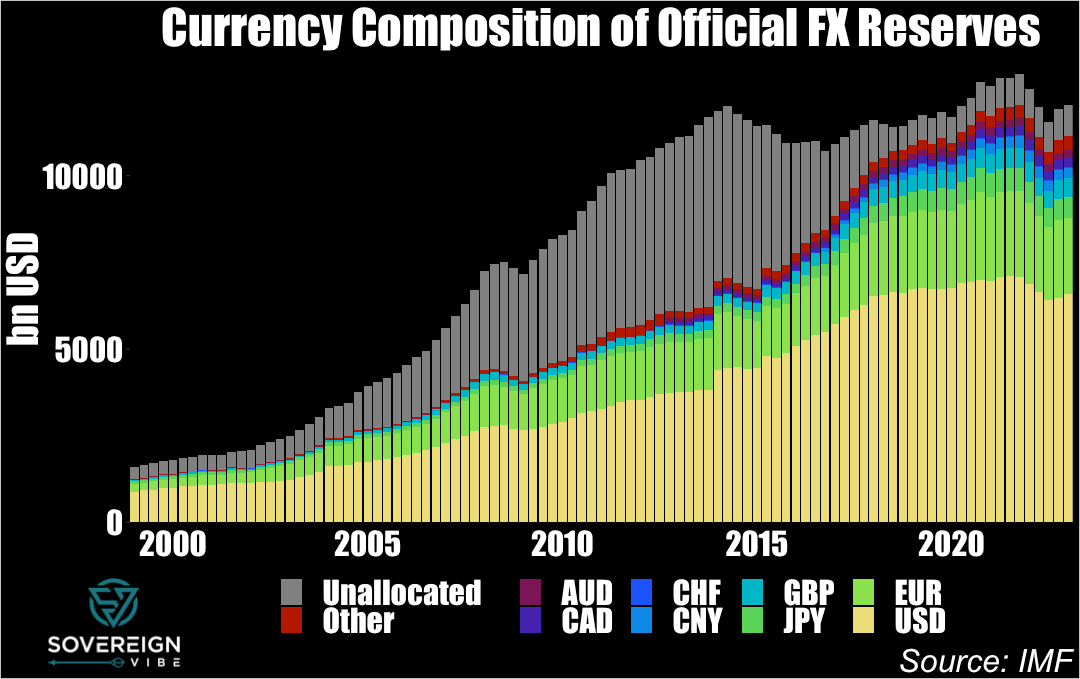

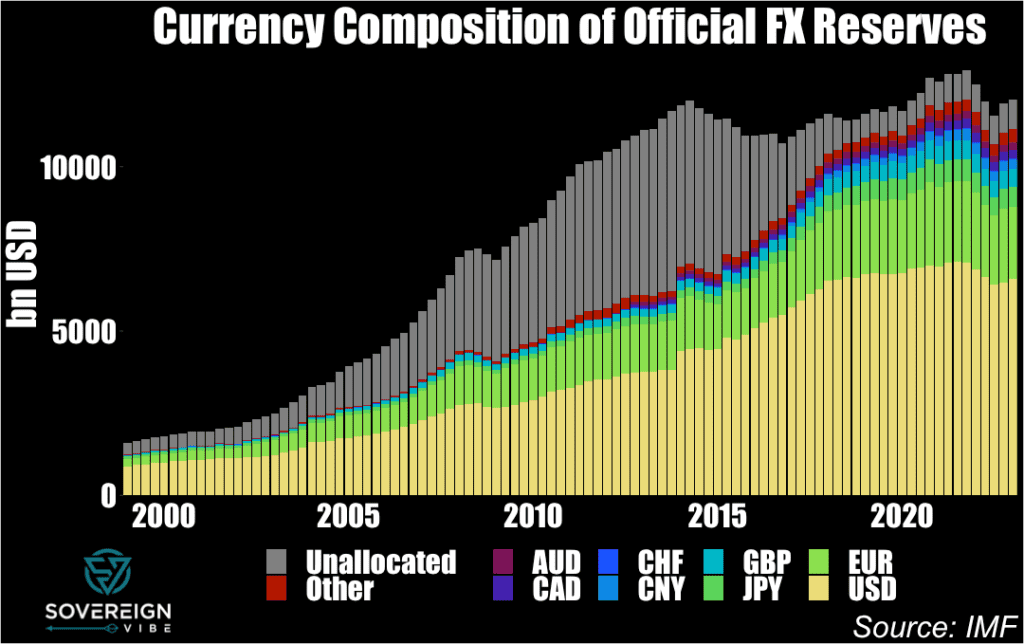

This status quo also reinforces the US dollar’s status as the reserve currency because US current account deficits mean that the US can flood the world with dollars. The US can do this because of well-entrenched, large global demand of US assets, whether financial, real estate, or other. This is what gives the US Treasury its “exorbitant privilege” to borrow significantly, at low cost.

Savers around the world are always keen to invest in highly-diversified economies with strong property rights. Open capital accounts across most of the developed world make it possible for capital to move around nearly seamlessly for buying and selling assets. This is one reason why asset valuations across much of the Anglosphere seem so stretched, whether stock market valuations or residential real estate prices. Local workers, even in wealthy cities like New York, Vancouver, and Sydney, are being priced out by global capital.

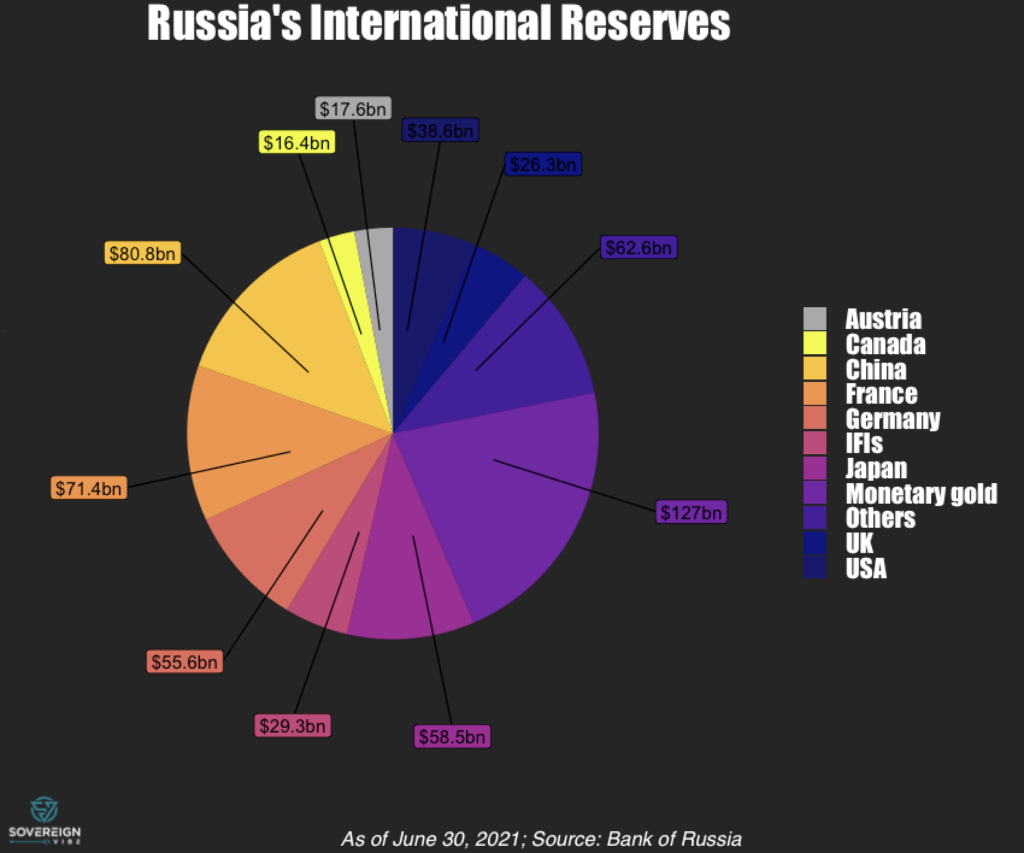

Moreover, a global economy awash in dollars is one where the dollar can be weaponized via sanctions. Dollar dominance also reinforces the power of US banks, which are already strengthened by domestic financialization.

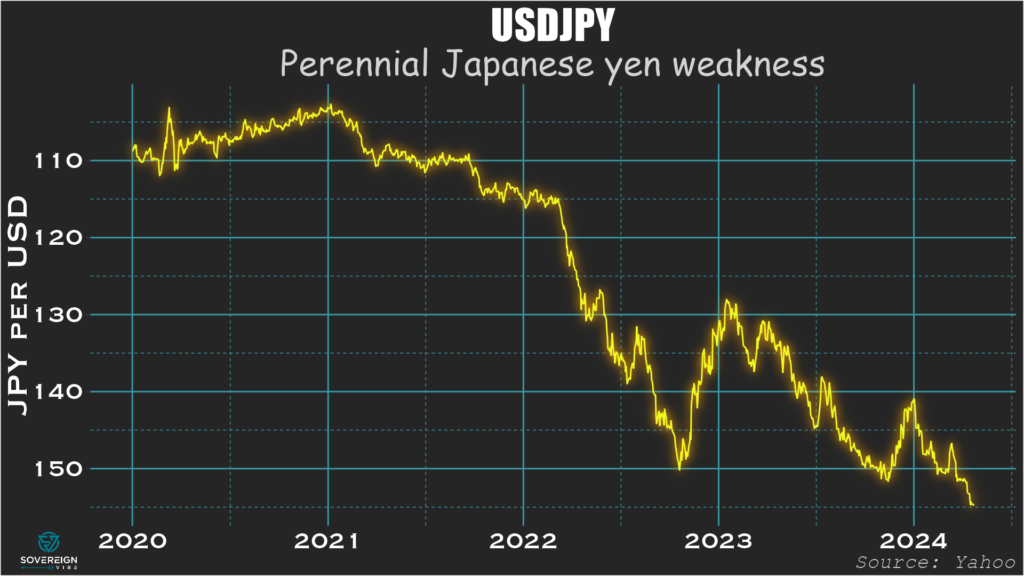

This is also a system that benefits US dollar strength. While a strong dollar hurts US exporters, no one in the US government or Congress really seems to care about export competitiveness beyond lip service. Worse still is the fact that an appreciating dollar is associated with lower trade volumes and more expensive debt servicing costs on dollar-denominated debt for emerging market issuers.

CAB surplus, high investment, low consumption

On the flip side are the economies running current account surpluses. First and foremost China, but also Germany, Japan, Russia, and – sometimes – Italy. One thing that these countries all have in common is rapidly-aging populations. People in prime working years tend to consume more due to higher income levels and spending needs, including children.

China, Germany, and Japan also under-consume because they subsidize production at the expense of consumption. If you’ve ever wondered why Japanese unemployment rates are so low, consider that a relatively small working-age population has a lot of domestic exporting industries to choose from. Or why wages and real estate prices are lower in Frankfurt and Berlin than in London and Paris. Germany has kept wages and consumption low to boost manufactured exports.

Unsustainable consumption imbalances

The global trading status quo doesn’t only damage the developing countries that need access to rich-world capital. These imbalances are also causing rot at the heart of G7 economies. For the US and other deficit countries, consumption is too high. Jobs and industries have been outsourced, while asset prices have skyrocketed out of reach for workers.

In Germany, Japan, and Italy, consumption is too low in these aging societies with external surpluses. Domestic industry has survived, in part thanks to the typically-abundant savings of the elderly.

Balanced consumer demand is needed across advanced economies, in China, and beyond. Only then will more stable electoral politics return to the G7.