EM convergence to rich-world wealth levels is concentrated in Europe and Asia.

When I read a recent piece by Ruchir Sharma about a growth revival under way in emerging markets, I had to start investigating.

Apparently, a higher-than usual proportion of EMs (88%!) will have GDP per capita growth higher than the US in 2025-29, if IMF forecasts are anything to go by.

It seems that raw materials exports for green tech, an AI-related boom in chips and electronics, and ongoing re-shoring/friend-shoring of supply chains will be major drivers of EM resurgence. And that could well be.

My own view is that the winners and losers will be differentiated by which countries manage to move up value chains to the export of services and manufactured goods rather than natural resources.

That’s simple economic reasoning and far from contrarian. But it goes against the “Africa Rising” or “African Century” narrative that I so often hear.

Expect EM Asia ex-China, including India and ASEAN, to do continue doing well over going forward, though China will no longer be a main driver of that growth story.

EM Europe has also been overlooked as a bit of a dark horse but has posted some impressive wealth gains in recent years. And it’s poised to develop further.

For Africa, LatAm, and the Middle East & Central Asia, the future is somewhat cloudier. I’d even go so far as to say that I’m pessimistic on wealth creation keeping pace with breakneck demographic growth in Africa.

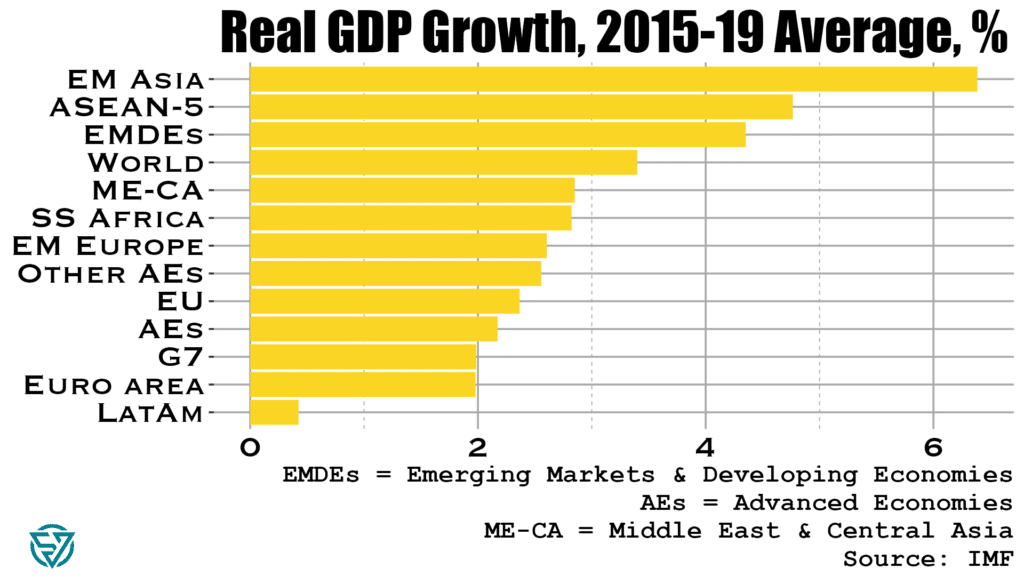

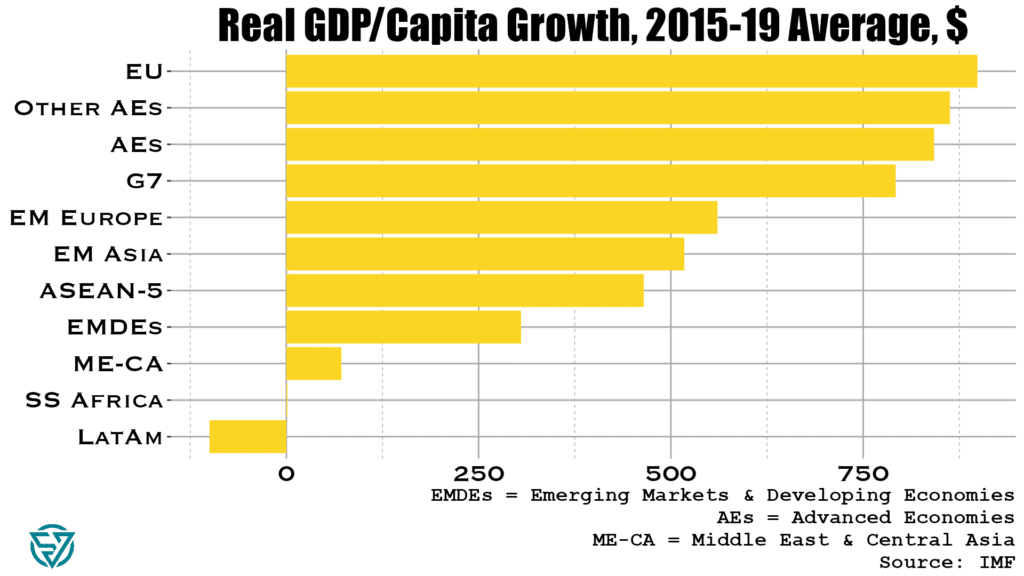

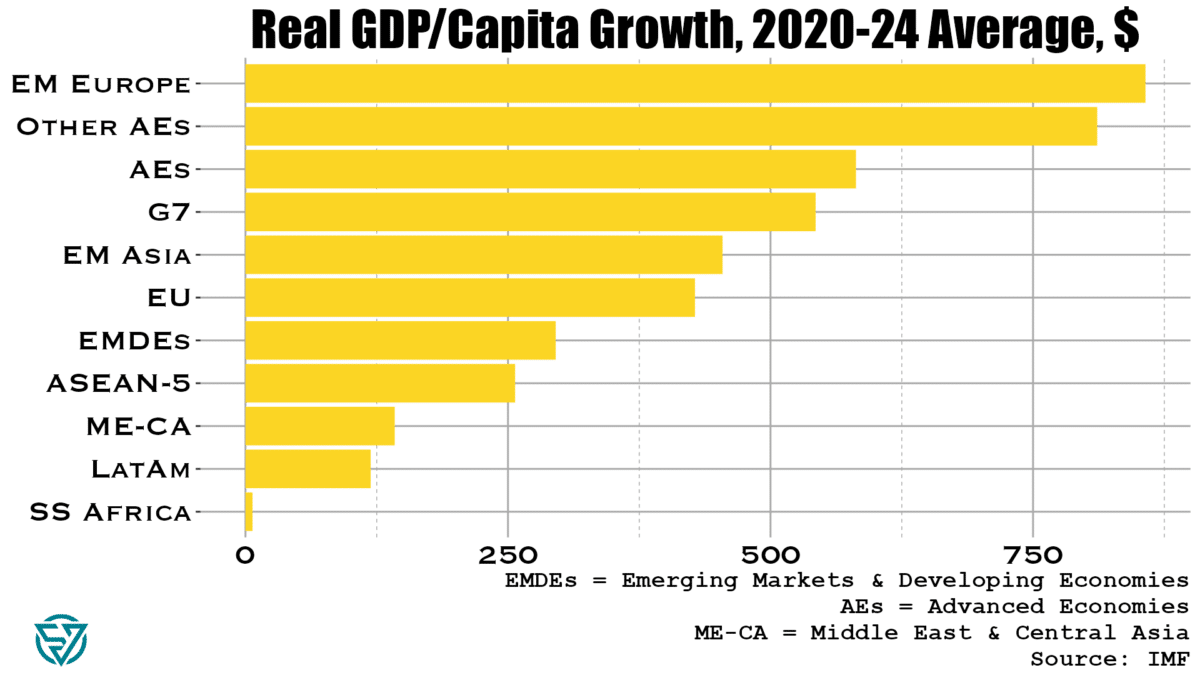

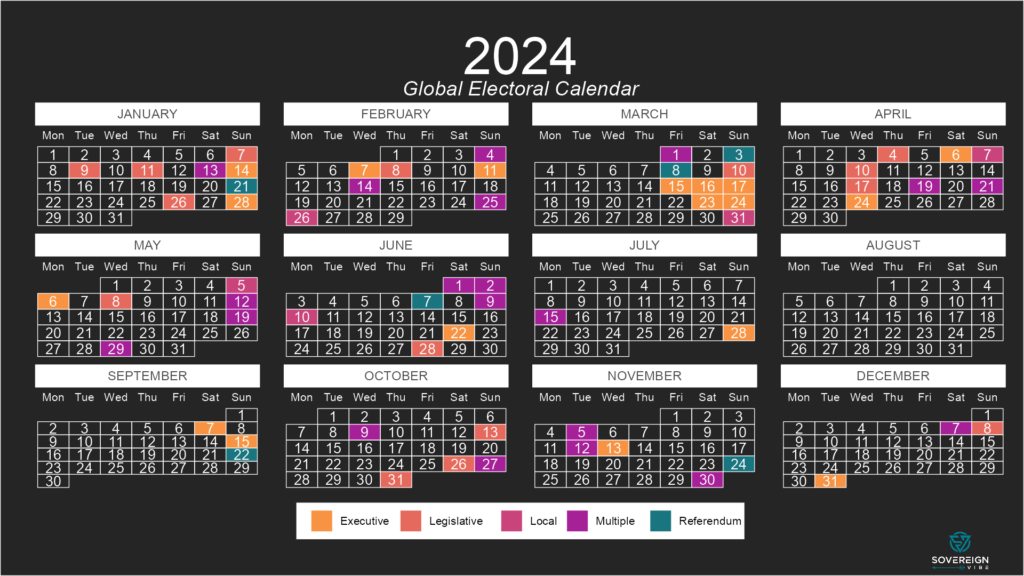

I’ve prepared some charts to help you visualize how the IMF’s data describes the past, present, and future of world regions in terms of:

- average annual GDP growth; and

- average annual GDP/capita growth, in purchasing power parity-adjusted constant 2017 US dollars.

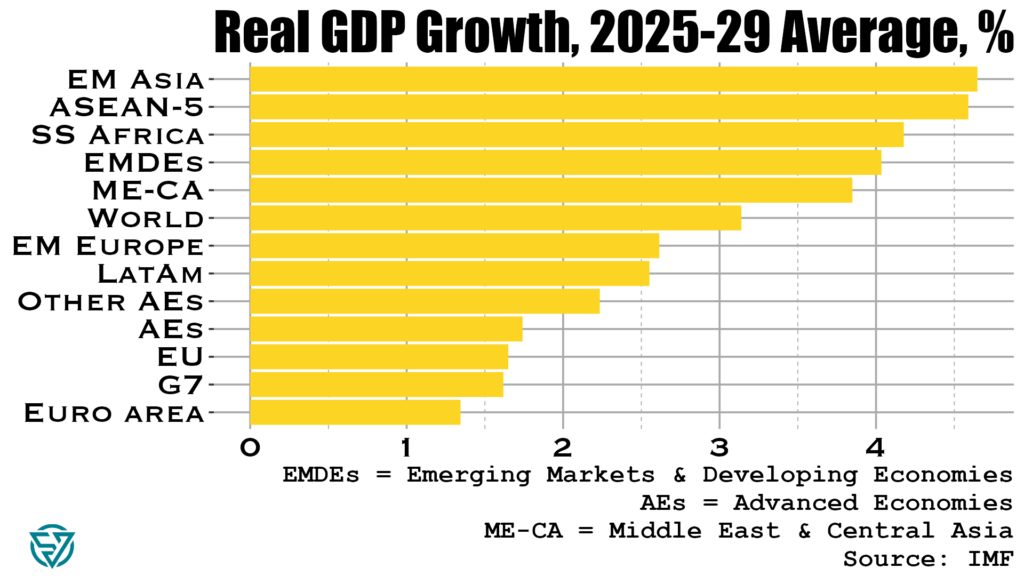

2025-29: Looking Ahead

The charts below show how emerging economies in Asia, including ASEAN, are poised to grow quickly over the next five years. The outlook also seems promising for Africa and for emerging markets as a whole.

Conversely, the IMF forecasts weak GDP growth for advanced economies. Slow growth is nothing new in Western Europe, but a sluggish G7 points to a slowdown in the US economy.

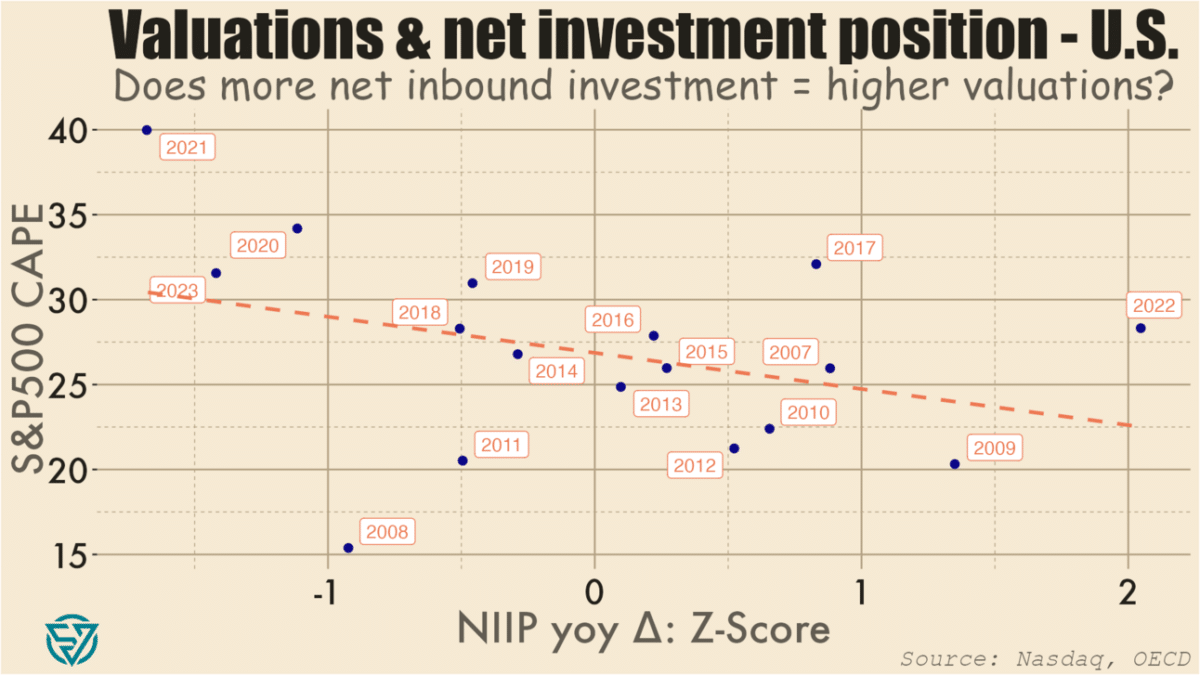

This could well be, given currently-large US deficits are draining future resources for productive investment.

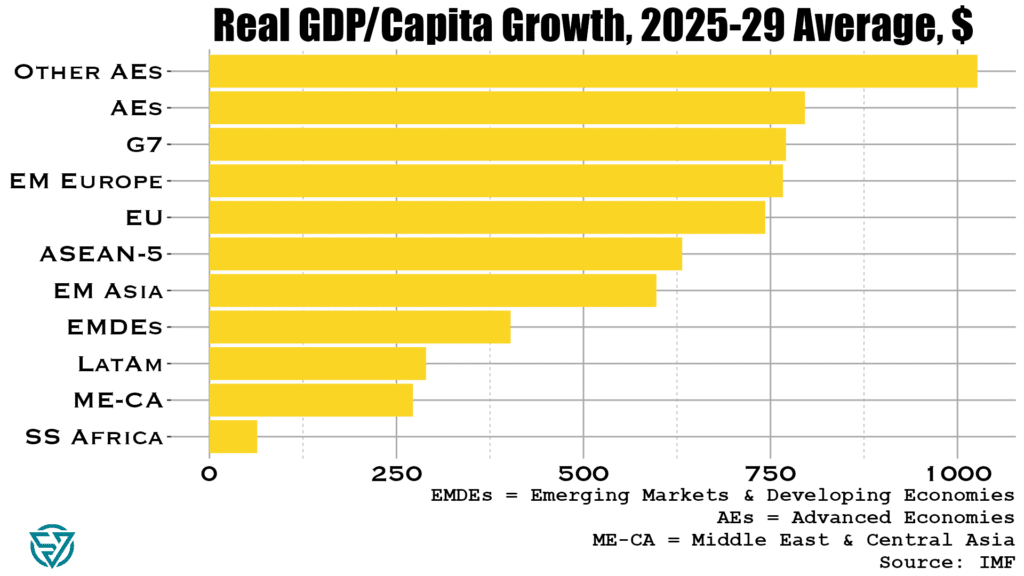

On the GDP per capita metric below, Africa is dead last in the IMF’s forecast.

Sure, since the levelof GDP per capita is lower in poor countries, a small dollar change is actually larger in percentage terms in Africa than the same dollar amount would be in a richer country.

Still, these GDP per capita numbers are adjusted for purchasing power and for inflation.

So a less-than-$100 increase in income annually on average over the next five years is abysmal, especially given the importance of combating poverty and migration crises.

The per capita GDP growth forecast also looks lackluster for the Middle East, Central Asia, and Latin America.

On the other hand, advanced economies and EM Europe look poised to benefit from the most average annual dollar wealth creation.

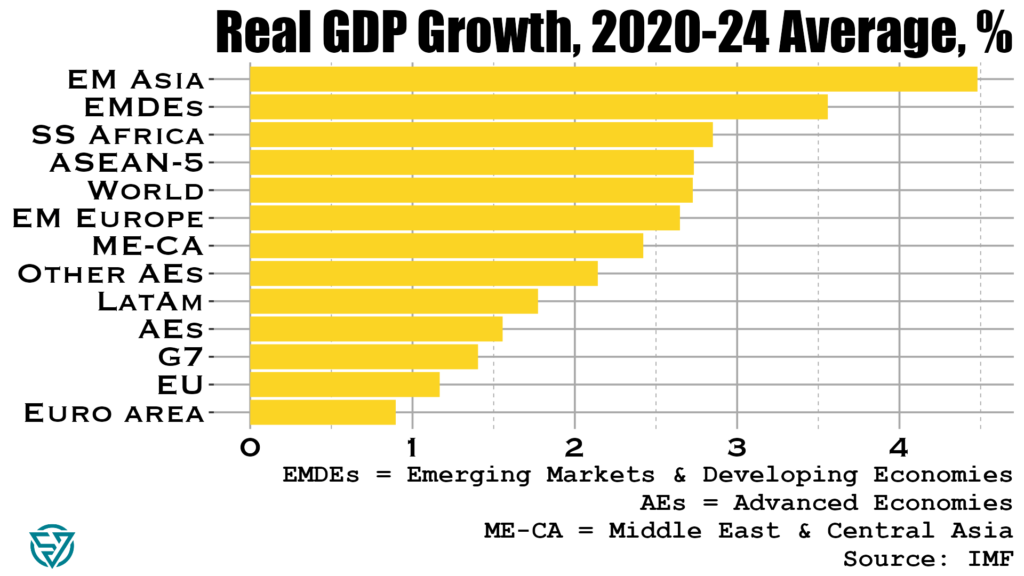

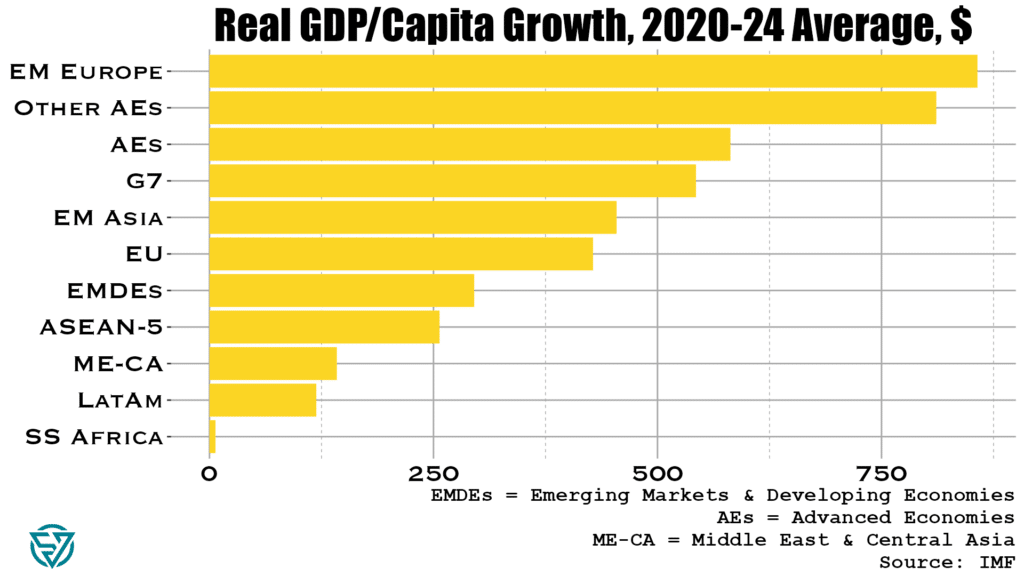

2020-24: The Pandemic & Its Aftermath

The past five years have have been rough, with the global economy suffering from the polycrisis of the Covid-19 pandemic, surging inflation, and conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East.

Advanced economies, and especially Europe, have had the weakest average annual GDP growth, along with LatAm.

While it comes as no surprise that to see EM Asia at the top of the 2020-24 GDP growth list, EM Europe topping per capita GDP growth is surprising, given the war between Russia and Ukraine.

Africa managed nearly 3% average GDP growth during this period, so the continent is actually developing. But it is not doing so quickly enough to outpace its demographic boom, which is why it ranks last once again on GDP per capita growth.

It has been a challenging five years for most EM regions in terms of per capita GDP growth, while advanced economies have fared well.

2015-19: Looking Back

The latter half of the 2010s share some similarities with 2020-24:

- EM Asia and ASEAN posted strong headline GDP growth.

- All advanced economies experienced strong GDP/capita growth.

- Africa and LatAm – and, to a lesser extent, the Middle East & Central Asia -fared worst on GDP/capita growth.