Following the release of sovereign debt stress heatmaps for 82 market-access countries, the underlying data for nine indicators for near-term risks is now available in the dashboard below. This first iteration facilitates visualization of each variable since 2010, with the possibility of viewing multiple countries simultaneously for comparative purposes. This tool is based directly on the IMF’s model for detecting the probability of sovereign debt strains 1-2 years ahead, as described in its 2021 Debt Sustainability Framework for Market-Access Countries. In addition to the IMF’s own documentation, past posts on this site describe the model and its indicators in more detail:

- Institutional quality

- Stress history

- Current account / GDP

- Real effective exchange rate: 3-year change

- Credit gap to the non-financial private sector / GDP (t – 1)

- General government debt / GDP: 1-year change

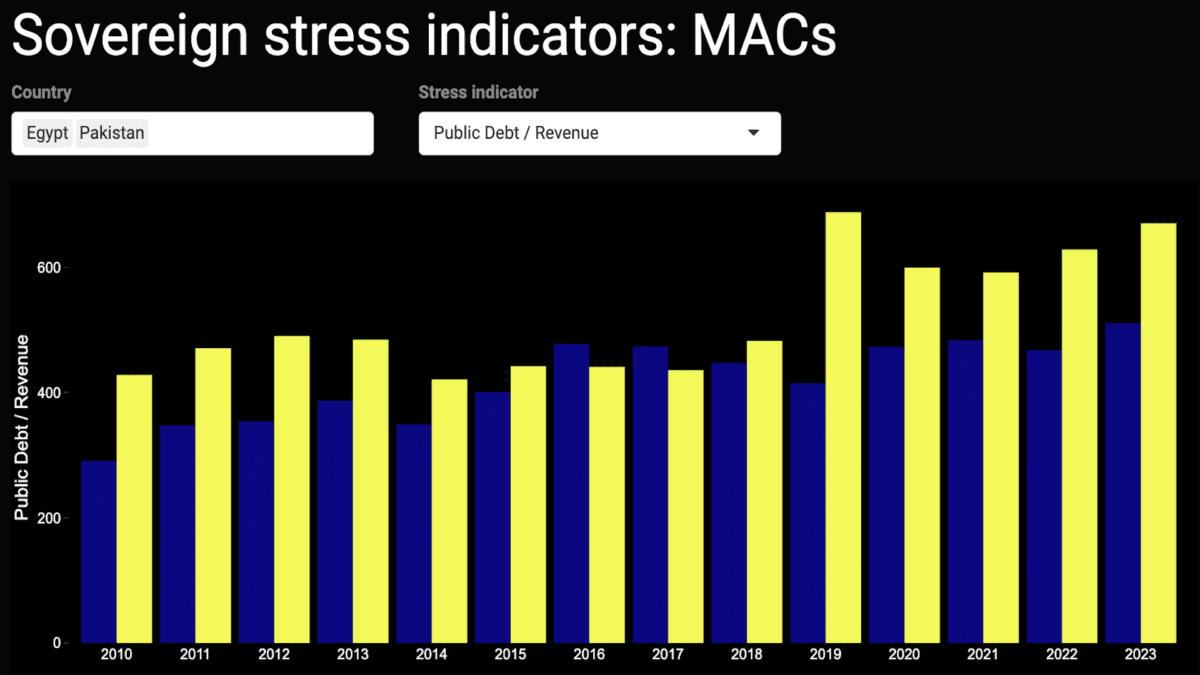

- Public debt / Revenue

- External public and publicly-guaranteed debt / GDP

- International reserves / GDP

Future iterations

For the time being, this dashboard allows for users to view only one indicator at a time, and excludes one of the IMF’s ten independent variables – the one-year change in the VIX index.

A further improvement for future versions concerns the change-based variables, as it would be helpful for readers to also – or only – view the level of REERs and general government debt (and of the VIX, if included).

Moreover, an augmented dashboard for broad monitoring of sovereign debt strains would have to include interest payments, amortization schedules, gross financing needs, central bank interest rates, and more information on exchange rate dynamics, inter alia.

Missing data

Lastly, working with this data from a range of official, reputable sources highlights severe deficiencies in coverage. In some cases, the data is missing outright:

- For instance, World Bank data would have us believe that Israel has no external PPG debt or that Jordan has no international reserves, which is untrue in both cases.

- Similarly, BIS data on credit gaps is only available for around 40 countries, though these are easily estimated for a much larger set of countries using World Bank data.

Despite these oversights from multilateral data sources, it is still useful to have broad overviews of the sovereign debt landscape for those needing to view which parts of the system are coming under strain. Of course, paid data sources can help plug these data holes.

But, given efforts at the IMF, World Bank, and elsewhere to advocate for sovereign debt transparency, surely some of the lowest-hanging fruit must be for the multilateral institutions themselves to improve their own data collection and dissemination practices to make relevant data more widely-available.