With the African National Congress party having endured a crushing defeat in South Africa’s election on May 29th, the political horse-trading around forming a minority government is already well under way. The final tally shows the ANC receiving 40% of the votes and 159 of the parliament’s 400 seats, a sharp drop from the 230 held previously.

Coalition-forming

These are uncharted waters in the post-apartheid era, as the ANC has lost its parliamentary majority for the first time in three decades and now finds itself constrained to seek coalition partners. Although many observers expected a challenging vote for the party, the scale of this electoral setback and its ramifications are still sobering.

The market-oriented, center-right Democratic Alliance continues on as the assembly’s next-largest party with 87 seats and is amenable to coalition talks, as parties seek to strike a deal before a parliamentary session begins in two weeks. Ex-president Jacob Zuma’s uMkhonto weSizwe party is in third position with 58 seats, though the personal antagonism between Zuma and the ANC’s leader, President Cyril Ramaphosa, likely precludes any bargain between the two.

Macro mismanagement, demographic dividends

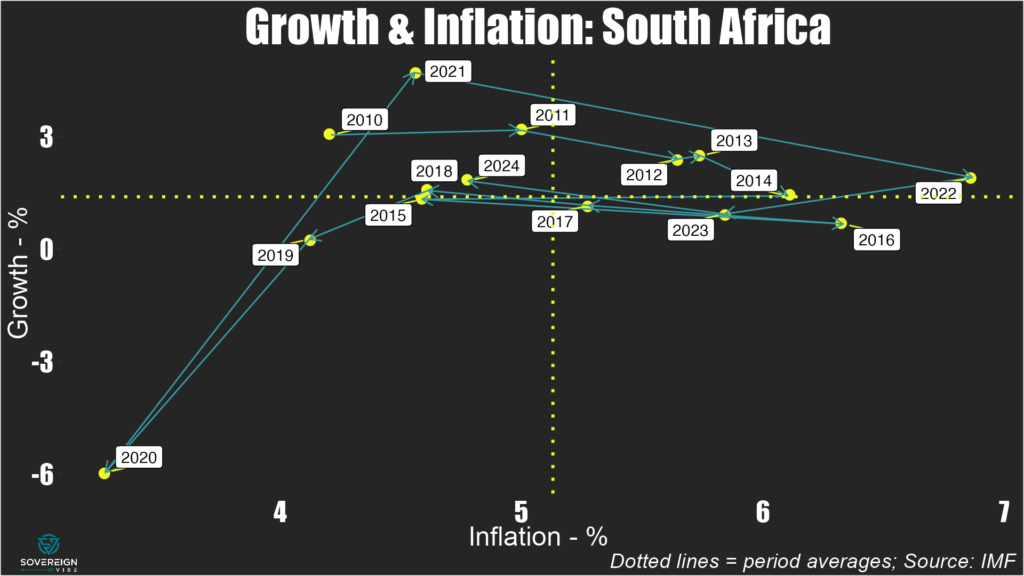

As the dust settles over this result, a quick look at some macro variables helps explain why the ANC got thrashed and where South Africa might be headed. Since 2010, average annual real GDP growth has been lackluster, at less than 1.5%, while inflation has been above 5% on average. Budget deficits have mostly been in the range of -4% to -5% of GDP for the entire period. The current fiscal approach is probably unsustainable over the long term, especially given that these spending overruns don’t seem to result from long-term investments in key areas. The woes of the national power grid operator Eskom serve as a prime example.

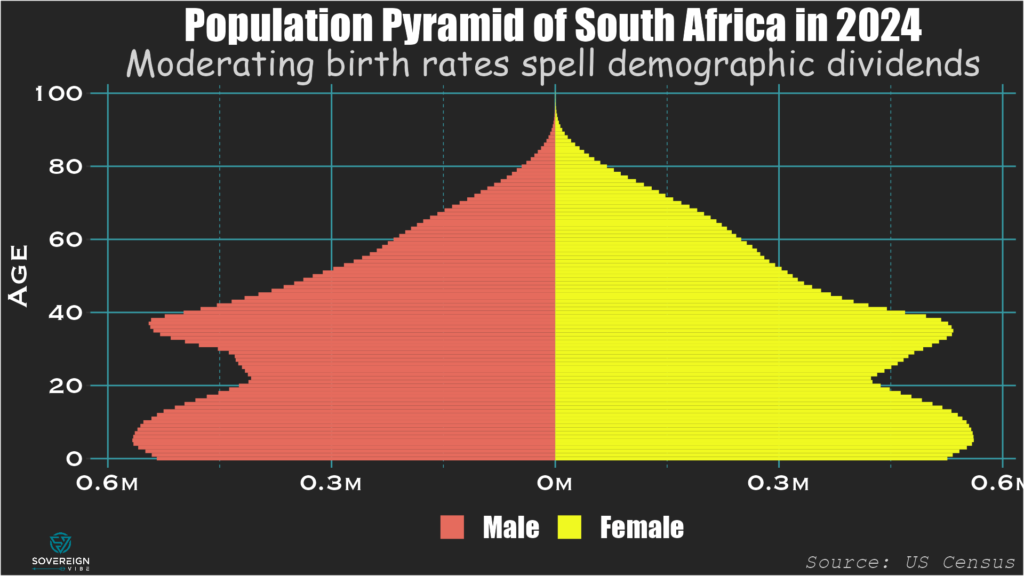

One outcome from the ANC’s economic policies is that GDP per capita has failed to rise significantly over the past two decades: the $6800 recorded in 2022 isn’t far above the $6100 registered in 2006. Indeed, real output growth has barely been able to annual outstrip population growth, which after dropping sharply in the 1990s, rose from the 2000s until peaking above 2% in 2015. Thankfully, annual population growth has moderated in recent years, and the fertility rate stands at a reasonable 2.37 births per woman, slightly above the replacement rate of 2.1.

As such, South Africa has a demographic advantage with a relatively small and declining share of the population that is outside the working ages of 15-64. At 53%, this is on par with the US and much lower than elsewhere in Africa (e.g. 80% in Senegal). The numbers of young South Africans set to enter the workforce over the short- and medium-terms is large compared to the overall numbers of young and elderly residents, meaning that the country has a demographic tailwind to be harnessed – but only if the new government gets its policies right.