When it comes to appropriating Russia’s central bank reserves for supporting Ukraine, some influential Western constituencies seem to think that the G7 leadership can and should dish out punishment without considering trifling matters such as due process. Such has been the Western enthusiasm for championing the Ukrainian cause, that they might have been right about this – or at least they were until recently. Also, where in the world are the Bank of Russia’s frozen assets?

Back in 2022, some of the many sanctions that several Western countries imposed on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine ended up freezing a lot of Russian assets held in various jurisdictions. The Bank of Russia’s immobilized reserves stand somewhere in the $300-350bn range, though it’s not quite clear where exactly it is all held. The quantum rises further, to around $400bn, if one includes the $58bn of Russian billionaire money also currently under sanctions.

That’s a lot of cash, obviously: Ukraine’s nominal GDP is only about $160bn, after having dropped by a third in 2022. With much of Ukraine’s economy and infrastructure in ruins and amid some setbacks on the battlefield, calls for repurposing Russia’s reserves to support and rebuild Ukraine have gained traction in recent months.

Location, location, location

As with so many other examples of opacity plaguing the international financial architecture, it’s unclear where exactly all of the Bank of Russia’s frozen assets actually are. Location matters because it will have at least some bearing as to how any appropriation gets carried out.

The little we know

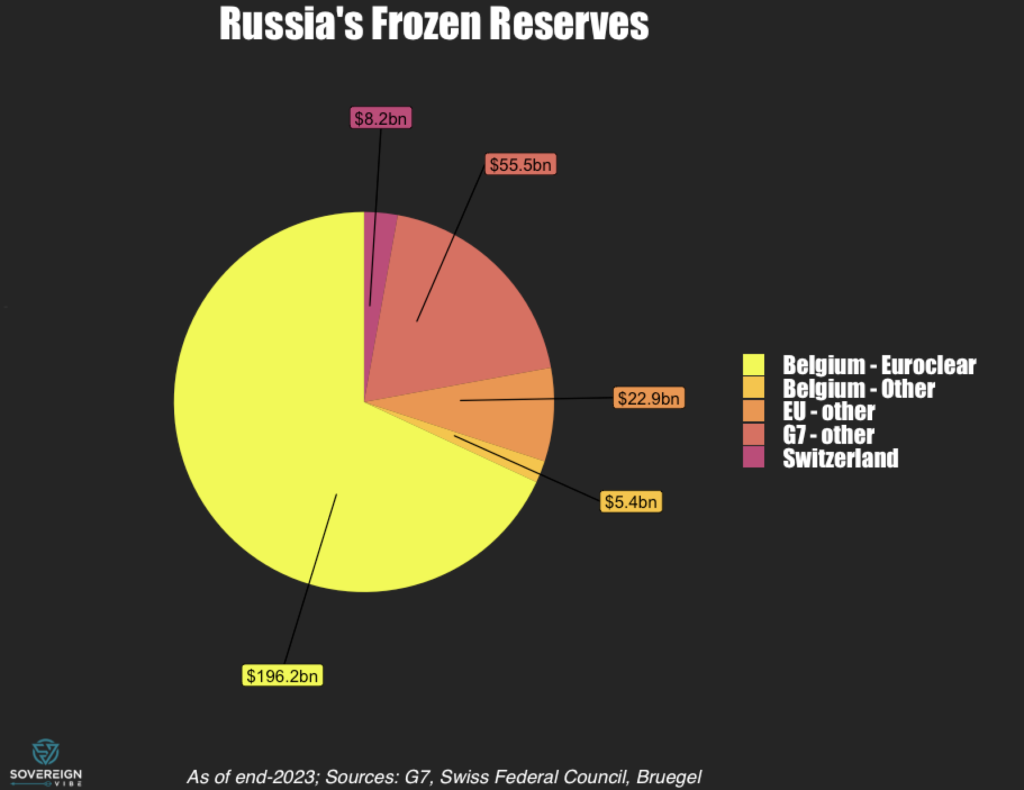

The chart below is based on a G7 finance ministers’ statement in October 2023 and information posted on Switzerland’s government website in May 2023. The total in the chart comes out to just under $290bn, using current exchange rates, with the Belgian central securities depository Euroclear holding the lion’s share.

Amid reports of $300-$350bn in immobilized Russian central bank reserves, it’s hard to tell where those other $10-60bn in assets might be – or if those numbers are just entirely made up.

Even the “identified” locations in the chart are ambiguous, with the “EU – Other” and “G7 – Other” categories accounting for nearly $80bn.

Detective work

It turns out I’m not the first person to be puzzled by the mysterious whereabouts of Russia’s frozen assets. Nor the second, nor the third.

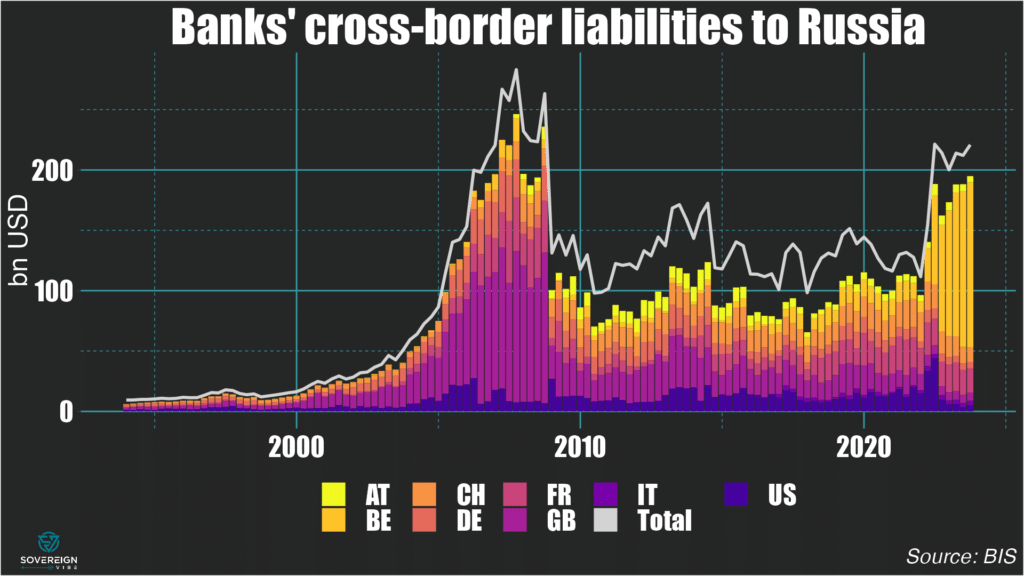

Inspiring myself from those who came before, I’ve taken a look at BIS data on banks’ liabilities to residents of Russia. Generally speaking, these seem to usually be in the form of deposits owned by entities and persons residing in Russia.

And sure enough, some of those massive Euroclear deposits show up in the chart above, around $136bn. This is less than the $196bn identified by the G7 statement, presented in the pie chart on immobilized reserves, meaning that the difference is presumably because $60bn of the assets aren’t bank liabilities (or simply weren’t reported to the BIS).

The amount of bank liabilities to Russia located in Switzerland are of a similar amount to the ~$8bn in Bank of Russia reserves that the Swiss authorities have reported sanctioning. As with Belgium, this suggests at least partial overlap.

As for the “Other EU” category representing $22.9bn in the first chart, France looks like the primary EU location based on its sizable cross-border bank liabilities to Russia. Press reports appear to confirm this – and that Germany also has Bank of Russia assets.

But it’s still unclear where those $55.5 bn in “Other G7” are held, though there aren’t too many suspects.

Pre-war breakdown

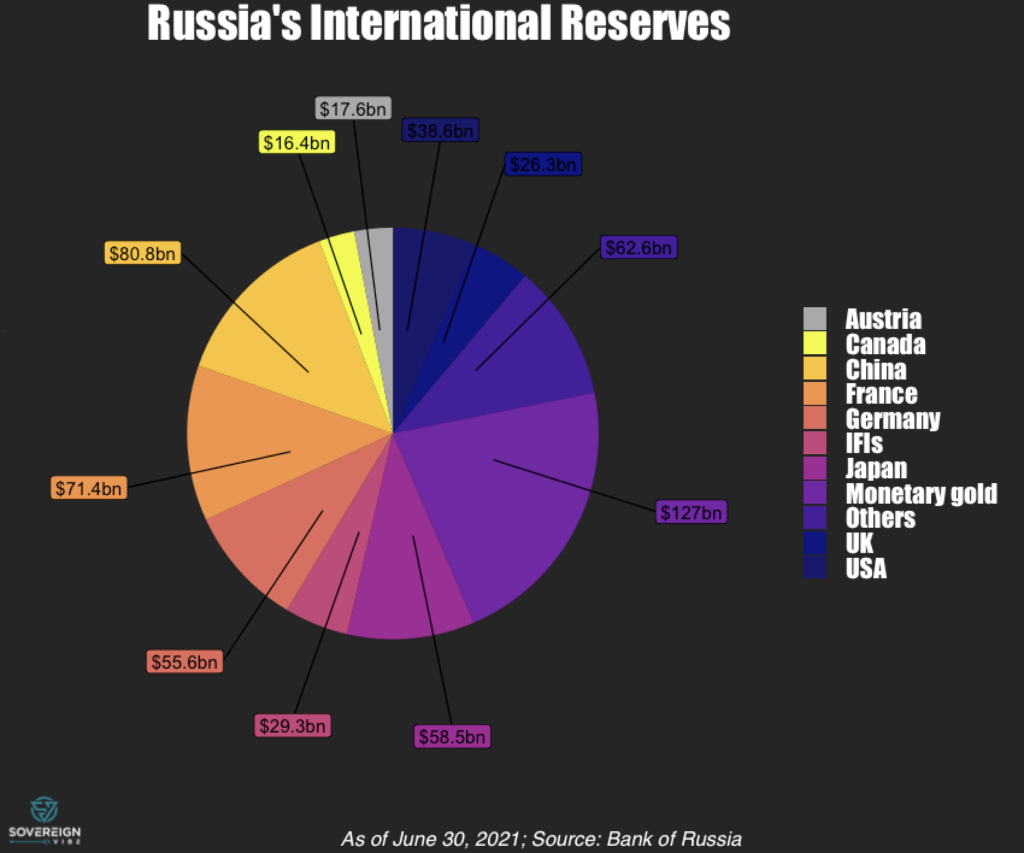

It shouldn’t really come as a surprise that the Bank of Russia has stopped publishing some of its statistics since the war escalated in 2022. But it sure makes it harder – or downright impossible – to know where its international reserves are located.

The last publicly-available data point is from June 30, 2021 and comes from the bank’s last Foreign Exchange and Gold Asset Management Report, released in 2022. Multiplying the $585.3bn total by the published percentages yields the following breakdown in the chart below:

The total held in G7 (i.e. sanctioning) countries – Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, UK, USA – sums to $284.4bn, which is roughly equal to the G7’s October 2023 statement.

Two things:

- First of all, France held the largest slice of any EU country at the time. Although Germany had a sizable chunk as well, this reconfirms France as the leading candidate for “Other EU.”

- Secondly, the $58.5bn of Bank of Russia reserves held in Japan in 2021 corresponds neatly to the $55.5bn in “Other G7” in the first chart, which is about as clear an answer as I can hope to glean.

To seize or not to seize?

On the face of it, the arguments for appropriating the reserves make good sense. Ukraine currently requires around $100bn of support annually, $40bn of which is for balance of payments and budgetary purposes and $60bn for the military. Moreover, estimated damage to Ukraine amounts to ~$650bn.

These are steep bills, to say the least, and Kyiv really needs all the money it can get. So, rather than having Western and Ukrainian taxpayers, and Ukraine’s creditors, foot the entire bill, using Russian money amounts to fair burden-sharing, or so the argument goes.

A poisoned chalice

Although there is a strong case for using Russian assets to help Ukraine, the counterargument is also valid. Seizing the assets could set a negative precedent and lead to further global fragmentation, in a world that is already suffering from the effects of deglobalization.

Ambivalence towards Ukraine in much of the non-Western world suggests that appropriating the Bank of Russia’s reserves would be poorly-received and erode trust in Western institutions and the international rules-based order. Worse still, doing so without a solid legal basis could backfire spectacularly in the court of global public opinion.

The irony is that the West would be perceived to be stealing from a regime that it itself views as a kleptocracy. Given their immense wealth, G7 member countries are not condemned to use the weapons of their Russian opponents against them. Despite budgetary pressures, inflation, and other economic challenges, US support for Ukraine pales in comparison to spending on past wars, indicating room for more support.

Outright appropriation could be a major win for the Kremlin, especially if done without a strong legal foundation, without really inflicting further damage on Russia since the reserves are already immobilized. Putin could use it as evidence of Western moral bankruptcy and institutional hypocrisy in outreach to receptive audiences in the Global South. Moscow’s kleptocrats would likely be gleefully rubbing their hands at a new excuse for expropriating any remaining Western businesses in the country.

Furthermore, in the case of seizure, it is unclear if any Western businesses, e.g. Danone, Carlsberg, will have a claim to compensation for their lost assets in Russia, or if all the money would end up going to support Ukraine.

Deep freeze

There are of course other intermediate solutions. The least controversial one is to send the €4.4bn in interest income earned by Euroclear in 2023 – and which belongs to Euroclear – on its sanctioned Russian assets to Ukraine. Another policy proposal is to use the assets as collateral for bonds, whose proceeds would be directed to Ukraine, though France and Germany – as well as the Euroclear CEO – have come out against it.

The most likely outcome seems to be that the assets remain frozen for the foreseeable future while Western policymakers find whether or not there is a path forward. There may not be, for the simple reason that Europe is reticent.

If Donald Trump returns to the White House next January, the prospects of collateralization or seizure would be even more remote. Even now, the Republican party has already abandoned its erstwhile fervor for the Ukrainian cause, holding up a $60bn aid package for Ukraine in Congress.

It’s all so unfortunate because Ukraine desperately needs support, including a Marshall Plan to rebuild. But the truth is that it needed a Marshall Plan 30 years ago, as did Russia and all the other post-Soviet republics.

By failing to help rebuild the post-Soviet space then, the West missed a unique chance to help foster stability in this part of the world and at a much lower cost – especially in blood but also in treasure. As a result, the price to pay is much higher today, whether or not Ukraine ends up getting Russia’s assets.