Pakistan and the IMF recently agreed on a program worth $7 billion, which appears woefully insufficient to resolve the country’s macroeconomic imbalances. The Fund claims that the Extended Fund Facility over the next 37 months intends to “cement macroeconomic stability and create conditions for a stronger, more inclusive, and resilient growth.” But this nothingburger of a deal – painfully, obviously so ($2.3 billion per year?) – will more likely achieve the opposite.

Some quick stats from 2023 pulled from my sovereign stress tracker, where Pakistan flashes red on reserve cover and debt-to-revenue:

- International reserves / GDP: 2.9% ($9.8 billion)

- Public Debt / Revenue ratio: 670

Some other figures worth bearing in mind:

- Gross financing needs = 24% GDP (~80 billion)

- Average annual interest payments over the next five years = ~6.5% / GDP (~$20 billion)

- Average annual principal payments over the next five years = $19 billion

- Imports typically range from $60-85 billion

- Export revenues range from $30-40 billion

- Tax revenues = ~10% / GDP (~$35 billion)

In 2023, the current account deficit narrowed to -0.7% of GDP (-$2.4 billion), but in the past these have been much larger (e.g. ~-$17.5 billion in 2022). But even financing small external deficits could prove difficult. With annual FDI generally under $2 billion and in the absence of other private capital inflows, the government will likely have to borrow more. This is a problem given already-high public debt levels at 77% / GDP, of which Pakistan owes 28% / GDP to external creditors.

So it is crucial that Pakistan runs small current account deficits or, dare I say it, surpluses. If the global trading system worked as it should (i.e. fantasy-land), non-commodity-exporting emerging and frontier economies should be expected to run current account deficits. The idea is that the current account surpluses of wealthy countries would fund the development and climate transition of poorer nations.

But since so few advanced economies run surpluses, I guess this nuclear power and world’s fifth-most populous country will just have to tighten its belt. Fantastic.

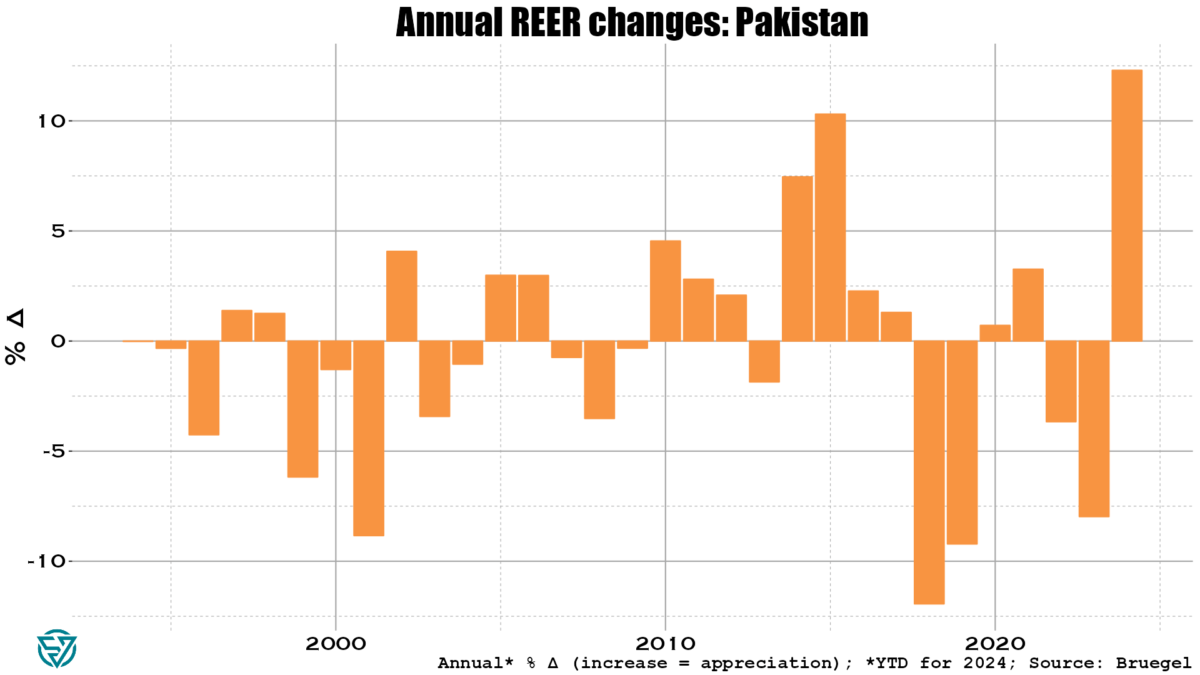

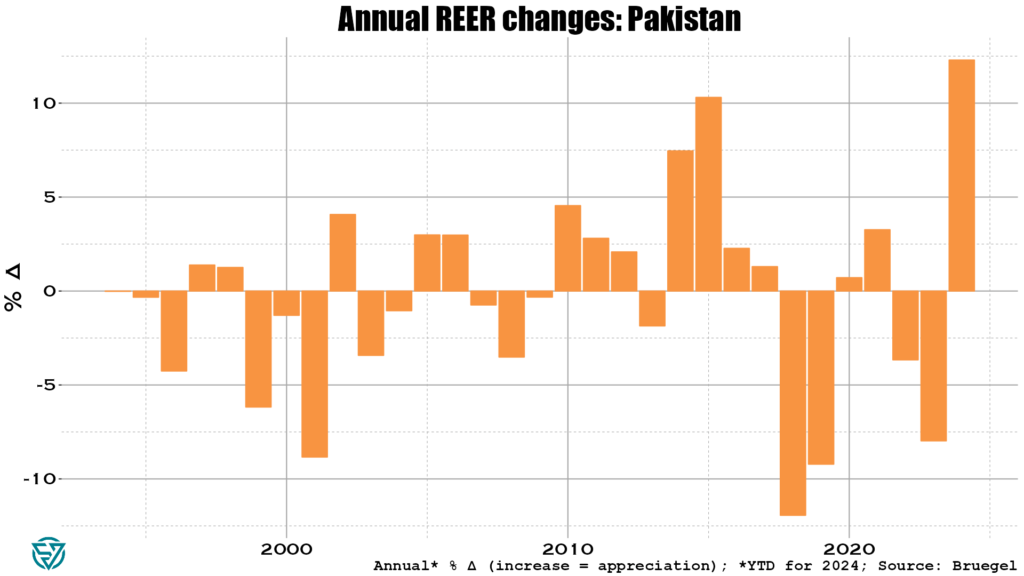

To avoid large external deficits, Pakistan’s real exchange rate needs to depreciate. Yet the exact opposite is happening, so don’t hold out too much hope for a small CAB deficit this year:

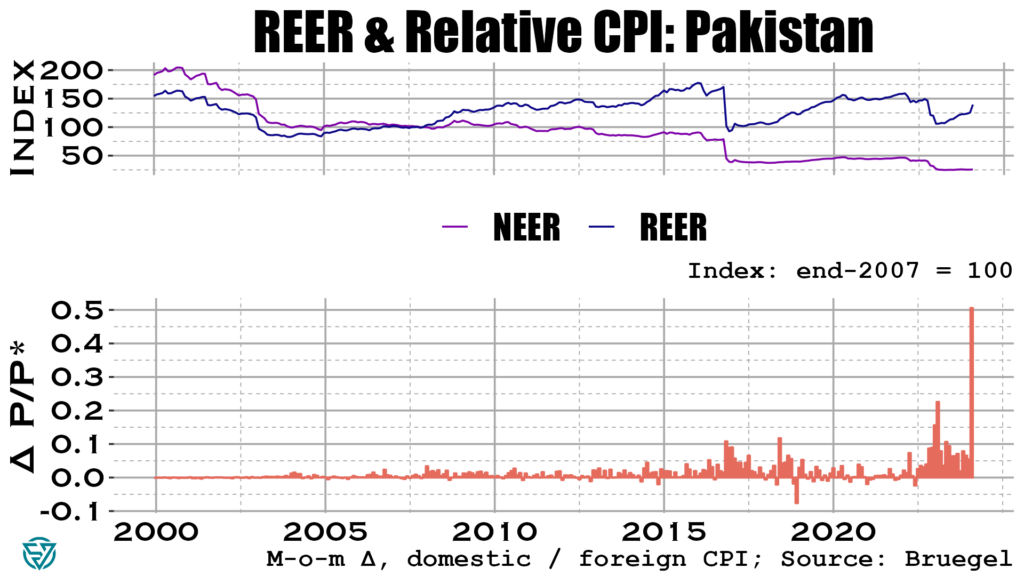

Olivier Blanchard once said that inflation is the canary in the coal mine. In the chart below you can see that Pakistan’s weighted inflation differential with its trading partners skyrocketed in May 2024.

Consider the alarm sounded. Even on the off-chance Pakistan manages to run a small CAB deficit in 2024 (say, like the -$2.4 billion in 2023), annual IMF support ($2.3 billion) will barely help bridge that gap. Islamabad still has to cough up about $39 billion in combined principal and interest payments every year going forward. This sum is roughly equivalent to export receipts and slightly larger than tax revenues.

This looks to be a solvency issue. And with inflation through the roof, it’s hard to see how this doesn’t get worse before it gets better. Watch this space.