As part of tracking the probability of credit stress among 112 sovereign issuers, one of the variables of interest in the IMF’s model is the credit-to-GDP gap. This indicator matters not only because of its predictive power for sovereign credit events but for many other reasons as well, including monetary policy transmission and government borrowing. When analyzed in conjunction with other data, credit gaps are useful barometers for detecting the presence of credit bubbles, economic over- or under-heating, and policy distortions such as financial repression and fiscal dominance.

Credit gaps are derived from observations of credit extended to the private sector as a percentage of GDP, and then a statistical technique, usually Hodrick-Prescott filtering, is used to smooth out the data points in the time series as a way to measure an underlying trend. While there are some shortcomings to this approach, including the arbitrary nature of the smoothing parameters used to identify the trend, it helps ascertain whether the cyclical component of lending is above or below long-term expected processes.

A credit-to-GDP gap is thus an actual observation at time t minus the trend in the same time period. As such, a positive credit gap is one in which lending is above trend, whereas a negative one is below. The credit gap coefficient in the IMF model is positive, as is the case in other models in the financial crisis academic literature, meaning that higher values are associated with an increased likelihood of sovereign debt strains. Looking at quarterly data through end-202212023 data will be presented in future posts on credit gaps. from the Bank of International Settlements on 43 countries plus the Euro Area, this first set of charts presents the actual credit-to-GDP ratios in blue, the smoothed trend in yellow, and the credit-to-GDP gaps in green.

In the chart above, credit gaps in this mix of developed (DMs) and major emerging market economies (EMs) are currently mostly negative. This makes sense given the tighter monetary policy stances around the world to combat inflation, with EM central banks having begun their rate-raising cycles2Some EM central banks are so far ahead of DM that they have already begun cutting rates in 2023. before their DM peers. A spike in credit gaps can also be observed in 2020 as policymakers worldwide lowered interest rates and facilitated the extension of credit as part of emergency measures to mitigate economic scarring at the height of the pandemic.

The BIS credit gap data is extremely useful for this set of countries, which, after all, comprise the world’s largest economies, and all the more so because it is available on a quarterly basis. The BIS describes its credit-to-GDP ratio as capturing total borrowing from all domestic and foreign sources by the private non-financial sector.3https://www.bis.org/statistics/about_credit_stats.htm However, other sources are needed for measuring credit to the private sector in other countries, and, thankfully, the World Bank has a similar indicator: domestic credit to the private sector by banks.4 https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/jobs/series/FS.AST.PRVT.GD.ZS The World Bank data series has far broader country coverage than the BIS data, thus opening vast additional swathes of the world to analytical coverage.

In contrast to the BIS data with its inclusion of both domestic and foreign credit to the non-financial private sector, the World Bank indicator appears to only include domestic sources of financing. Moreover, the BIS data appears to include sources of non-bank financing, unlike the World Bank data. Taken together, these two differences likely explain much of the discrepancy between these two datasets. Further, the World Bank data appears to only be available at a yearly frequency, thus requiring the BIS quarterly data to be transformed to yearly averages for the purposes of comparison.

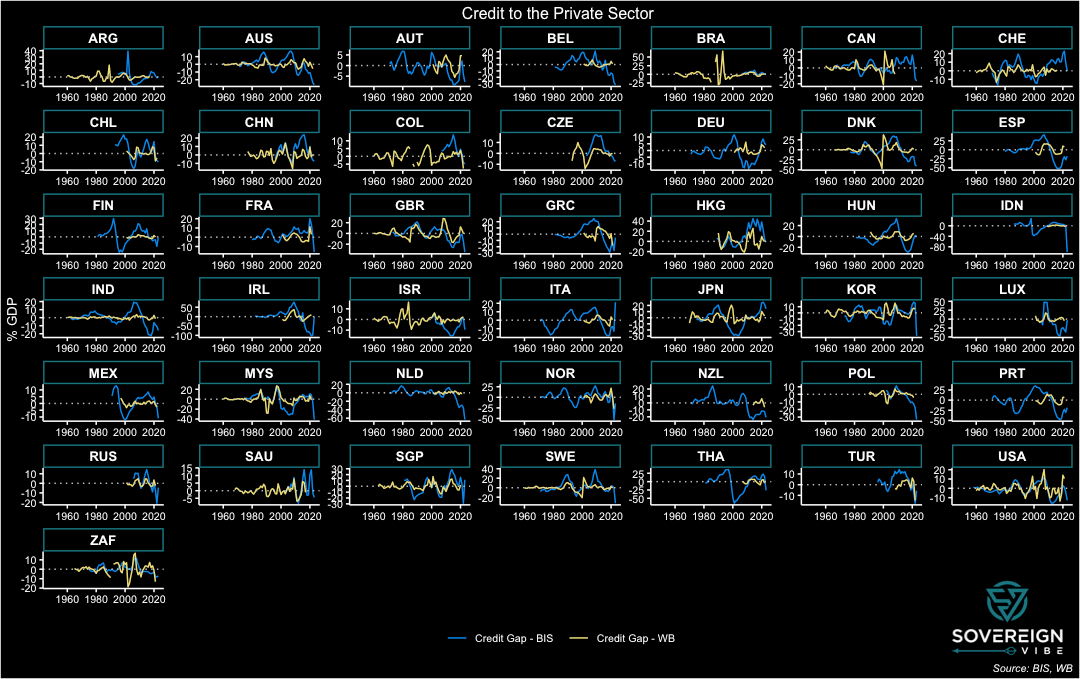

The charts below present BIS data in blue and World Bank data in yellow, in yearly form through end-2022 in both cases. As seen above, the BIS provides credit gap and trend data alongside its credit ratios and uses a one-sided Hodrick-Prescott filter with the smoothing parameter λ set to 400,000 for this quarterly data. The World Bank only provides its credit ratios on a standalone basis, meaning that the trend and credit gap need to be estimated independently. This is simple enough for one country, and thankfully panel statistical techniques enable scalability for quick estimation across a large number of countries and years. As such, trends and credit gaps are derived from the World Bank’s credit ratios using a two-sided HP filter with λ = 100, the recommended setting for annual data.

Consistent with the inclusion of foreign sources of credit, the BIS credit ratios are usually higher than those from the World Bank, especially in many European countries, e.g. Luxembourg and Belgium. Elsewhere, the figures track more closely, as is the case with Japan, Malaysia, and the UK. The US and China also fell into this category, but the datasets have diverged in recent decades for those countries. Surprisingly, there are also a few countries where the World Bank ratio exceeds the BIS reading, despite the former excluding foreign credit sources, with South Africa and the US standing out most prominently from this perspective.

The point of comparing the two datasets is to use the BIS as a benchmark to get a sense if the World Bank data is at least somewhat aligned with the former and it is any good for predictive purposes. Certainly, the similar characteristics of the actual and trend data above are a positive sign. As for the credit gaps themselves, the BIS and World Bank figures are presented below. While there are large differences in most countries, there are also similar processes at work in many countries, e.g. the United Kingdom, Malaysia. The BIS credit gaps appear to be more volatile than those of the World Bank, which could be explained by the former’s inclusion of foreign lending: capital flows of the portfolio variety, which includes debt, are prone to sudden stops and starts.

To simplify further, the difference in the BIS and World Bank credit gaps, where the former is subtracted from the latter (difference = WB – BIS), features in the chart above. Ideally, the data readings would all be horizontal lines at zero or at least resemble a stationary process hovering above and below zero. While some countries do have these features – Sweden, the UK, the US, and Switzerland, among others, a large cohort exhibits some sort of bias. A statistical test of this difference in credit gaps across this panel of countries over these years would likely reject the notion that the difference is equal to zero. Nevertheless, the World Bank domestic credit to private sector by banks indicator seems fit for purpose, particularly given the large role that domestic banks play in credit provision in most economies.

Future posts will expand further on the importance of credit gaps and present broad country coverage of World Bank credit gap data.

- 12023 data will be presented in future posts on credit gaps.

- 2Some EM central banks are so far ahead of DM that they have already begun cutting rates in 2023.

- 3https://www.bis.org/statistics/about_credit_stats.htm

- 4https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/jobs/series/FS.AST.PRVT.GD.ZS

2 replies on “Mind the credit gap”

[…] BIS data on credit gaps is only available for around 40 countries, though these are easily estimated for a much larger set of countries using World Bank […]

[…] post follows on from previous credit gap analysis on this blog and how this indicator helps estimate the probability of sovereign debt strains,1As a […]