A high-level snapshot of the structure of outstanding external sovereign debt burdens for low-income countries and reflections on the G20’s pandemic-era DSSI policy and its successor, the Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI.

LIC debt burdens

During last month’s IMF-World Bank Spring Meetings, I listened to a discussion on debt crisis resolution between civil society activists and IMF staff. The vastly different frames of reference, language, and motivations on low-income country (LIC) debt playing out were captivating. It is precisely this clash of worlds that the sovereign debt space needs more of as stakeholders search for the best policies to foster inclusive growth and eradicate poverty.

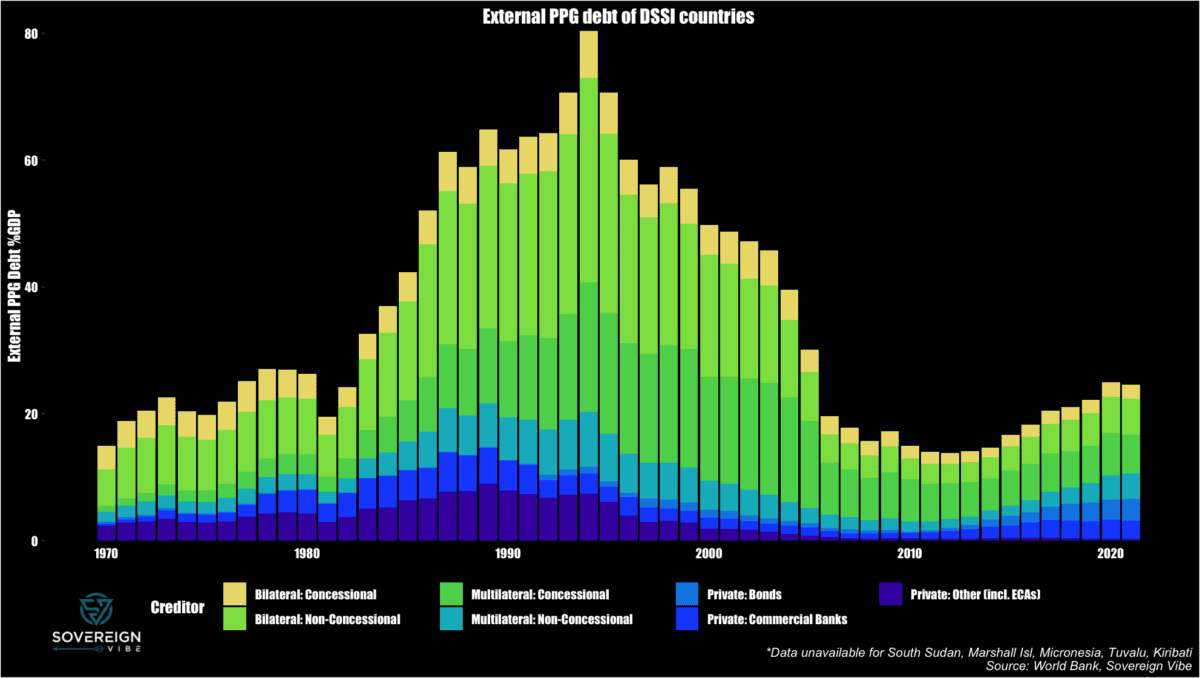

Civil society organizations (CSOs) have a long-standing and well-known position on LIC external sovereign debt: in a nutshell, just cancel it. Indeed, rising external debt burdens in LICs in recent years have fueled more calls for debt forgiveness. Looking at the DSSI-eligible LICs, the rapid increase in external sovereign debt in the 2010s does give pause for concern. While the overall external public and publicly-guaranteed (PPG) debt load hovered around $200 billion throughout the 1990s and 2000s, it surpassed the $600 billion mark in 2021.

Contrast the CSO perspective with IMF staff assertions that external sovereign debt strains in LICs are less severe today than in the past. Needless to say, the CSO representatives were essentially unanimous in taking issue with this position, labeling it as provocative. IMF staff presented a chart resembling the one below, highlighting how external public debt-to-GDP was much heavier previously. In fact, the most acute strains occurred in the mid-1990s. These declined until the late 2000s, partly thanks to the Heavily-Indebted Poor Countries initiative (HIPC) from 1996 and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) from 2005.

While today’s external PPG debt ratios are less alarming, the growth of domestic capital markets in many LICs suggests that overall (i.e. domestic plus external) sovereign debt-to-GDP could be too high. Moreover, LIC sovereigns have borrowed more on non-concessional terms over the past decade, pointing to greater interest payment pressures.

The new data above will augment the DSSI dashboard in the Sovereign Vibe DataHub, where users can filter data by borrower and creditor.

The ill-omened DSSI

A New Hope

As COVID-19 swept across the world in the spring of 2020, the G20 introduced a new policy to ease the public debt strains of the world’s poorest countries: the Debt Service Suspension Initiative. The data above uses DSSI-eligible countries as a grouping because it is broadly representative of LICs. Also, the G20 has designated these 73 countries as eligible for the DSSI and its successor policy, the Common Framework.

The DSSI allowed for external public debt service payments to be suspended by eligible countries upon request from May 2020 until its expiry at end-2021. These included 72 of 76 countries then-classified as International Development Association borrowers.1Per World Bank classification, IDA and IDA/IBRD “blend” borrowing countries The G20 excluded Eritrea, Sudan, Syria, and Zimbabwe for arrears to the World Bank and the IMF. The DSSI included all2Except for countries not current on debt service to the World Bank and the IMF United Nations-defined Least Developed Countries, adding Angola to the beneficiaries.

Misfire

While laudable for its objectives, its rapid response to the pandemic, and for breaking new ground in cooperation between “traditional” bilateral lenders to LICs (i.e. Paris Club members) and “newer” bilateral creditors to LICs (i.e. China), the DSSI’s results were underwhelming. Only 48 out of 73 eligible countries participated. Beneficiaries received a mere $12.9 billion in debt service deferrals, with China providing the lion’s share of relief.

One of the chief criticisms of the DSSI is that it failed to galvanize debt service relief from private creditors. More to the point, official sector representatives have repeatedly criticized the private sector for not participating in the initiative. But these creditors were unable to do so without beneficiary countries requesting private sector relief, which virtually none did.3Grenada requested a private creditor payment moratorium before quickly withdrawing it.

The absence of deferral requests to private creditors partly stemmed from legitimate fears over sovereign credit ratings downgrades. This was certainly the case for DSSI beneficiaries with outstanding eurobonds. However, some eurobond issuers4e.g. Cameroon did request and obtain official sector relief, and avoided asking for private support. A further reason for the lack of requests is that many LICs have little or no outstanding external debt held by private creditors.

In any case, the exclusion of private creditors from the DSSI is a design feature that the G20, rather than private creditors, is wholly responsible for. Yet locking out private lenders may have had an unintended positive outcome on the DSSI. Allowing borrowers to request bilateral and private relief separately likely helped mobilize more payment suspensions from official creditors. While far from the ideal of inter-creditor equity, at least these LICs benefited from some official-sector deferrals during the DSSI.

From bad to worse: the CF debacle

More like Uncommon Framework

The G20 announced the Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI (CF) in November 2020 as its new debt restructuring policy. Policymakers meant for the CF to achieve two inter-creditor goals. The first is to facilitate coordination between China and other creditors. The second is to rope in private creditors. The G20 opted for so-called “comparability of treatment” in the CF, meaning that the private sector is compelled to participate on the same terms.

But if borrowing country requests for CF treatment are anything to go by, seemingly the cure is worse than the disease. So far only four countries have come forward. Zambia, Chad, and Ethiopia did so in late 2020/early 2021, with Ghana following in H1 2023. As with the DSSI, the so-called credit rating impasse is likely one of the reasons rated borrowers are reluctant to involve private creditors. Case in point, Ethiopia’s sovereign credit rating was downgraded upon requesting CF treatment.5Zambia and Ghana were already in default upon requesting CF treatment, whereas Chad has no outstanding eurobonds and thus has no rating.

Showdown

Worse still is the lack of meaningful progress in Zambia and Ethiopia. A disagreement between the IMF/World Bank and Chinese creditors is reportedly holding up talks. The latter apparently want the World Bank to participate in debt restructuring. Yet the World Bank typically does not participate in debt re-profilings because this threatens its preferred creditor status (PCS). The Bank’s AAA credit rating and resulting ability to borrow cheaply from capital markets partly relies on PCS. This advantage enables the Bank to provide significant concessional lending to member countries, or so the argument goes.

China’s challenge of PCS strikes at the heart of the Western-led international financial architecture, mirroring its geopolitical challenge to the US-led global order. Beijing has also been asking for a greater voice in the Bretton Woods institutions. But with another American poised to become President of the World Bank, Washington appears unlikely to budge. Small wonder then that Zambian and Ethiopian authorities are losing faith in G20 multilateralism, turning instead towards bilateral engagement. The same can be said for other LICs, which likely view the CF as an undesirable last resort.

Meanwhile, a recent successful negotiation between Chad and its lenders has been heavily criticized for apparently limited concessions made by creditors, seemingly linked to recently-high oil prices. And the outlook for Ghana is also concerning, with the IMF having mandated that domestic debt be included within the restructuring perimeter as part of its program, a significant departure from recent common practice.

Gridlock

G20 Fractures

The gridlock surrounding the international financial architecture has emerged as a major challenge facing low-income sovereign borrowers today. The combined failings of the DSSI and the CF are largely a reflection of fractures within the G20, which are partly geopolitical. With the G7 sharing the table with China, Russia, and the Global South, diverging views define the G20. In fact, it is this representativeness that makes the G20 the world’s foremost policy forum. Yet competing viewpoints on security, Ukraine, trade, climate change, and other issues are hampering the organization’s effectiveness.

But the economic interdependencies are also quite different. China is now a bigger creditor to LICs than Paris Club members combined. Many stakeholders have criticized China in holding up CF negotiations, whether purposefully or due to its fragmented creditor landscape. Yet other official creditors are also at fault, specifically for failing to share information with private creditors on time.

Private creditors

G20 sovereign debt policy has indeed fallen short in appropriately engaging with private creditors. The CF process gives official creditors access to information, such as IMF debt sustainability analyses, before private creditors. Even if LICs had requested DSSI relief, net-present value neutrality for private creditors entails mark-to-market interest rates applied during payment moratoria. This contrasts sharply with public sector practice, where interest rates remain stable in NPV-neutral situations. Risk-aversion in 2020 widened many sovereign LIC spreads. These higher spreads implied that any DSSI beneficiary requesting private participation would have likely faced a steep bill as the suspension expired.

With legally-binding fiduciary duty to asset owners, asset managers are reluctant to voluntarily defer payment or accept losses. Fundamentally, private credit represents property rights that require protection if private capital is to help bridge funding gaps in LICs.

All bets are off

Taken together, these dysfunctions in the international financial architecture could be just as challenging as the other headwinds LICs currently face. These include inflation, rising interest rates, geopolitical tensions, food insecurity, and subdued growth. The grit in the system seems so bad that the subtle message to LICs could well be that they should expect the debt forgiveness of the HIPC and MDRI initiatives again.

An optimist might say that the specter of HIPC 2.0 could be enough to breathe political life into a Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism (SDRM). This is a stillborn idea from 2001 for implementing structures mimicking domestic bankruptcy law. But such prospects seem remote, with the political will for an SDRM likely as absent as it was in the early 2000s, if not more. This is all the more unfortunate given an exciting 2021 IMF proposal for facilitating sovereign debt restructurings via auction. The real shame, of course, is the human suffering that international sovereign debt policy congestion will continue to cause in LICs.

- 1Per World Bank classification, IDA and IDA/IBRD “blend” borrowing countries

- 2Except for countries not current on debt service to the World Bank and the IMF

- 3Grenada requested a private creditor payment moratorium before quickly withdrawing it.

- 4e.g. Cameroon

- 5Zambia and Ghana were already in default upon requesting CF treatment, whereas Chad has no outstanding eurobonds and thus has no rating.