EMDE sovereign borrowers walk a tightrope in the fragmented creditor landscape.

One of the main themes permeating the 7th edition of the Sovereign Debt Research and Management Conference – aka “DebtCon” – held in Paris on 29-31 May was the increasingly challenging environment that sovereign borrowers face in accessing international capital and managing their balance sheets. These challenges are numerous and complex, with some of the best-known ones being the more diverse creditor landscape, implementation problems of key policies such as the G20’s Common Framework of Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI, and geopolitical fragmentation.

The Chinese impact

DebtCon is a particularly useful forum for finding solutions to the day’s most pressing sovereign debt policy issues. Not only does it bring together stakeholders from across much of the sovereign space, including borrowers, creditors, academics, and practitioners, but the conference is also focused and small enough for participants to exchange ideas more efficiently than at larger, sprawling events.

One of the most impactful discussions was the closing panel, which addressed the geopolitics of sovereign debt and best encapsulated the myriad challenges in the space. Take, for instance, increased creditor diversity: one of the key newer features – alongside the emergence of bondholders – is that China has established itself as the world’s largest bilateral creditor to lower- and middle-income countries over the past decade plus. Resolving debt crises has become harder as a result, with more debt exposure to China making it less likely for a sovereign borrower to complete a Paris Club restructuring. Similarly, debt to China is associated with longer negotiating times for IMF programs.

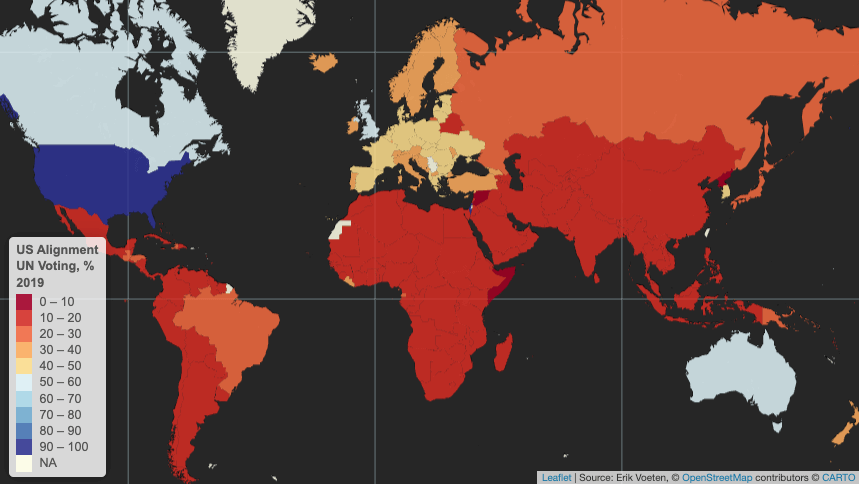

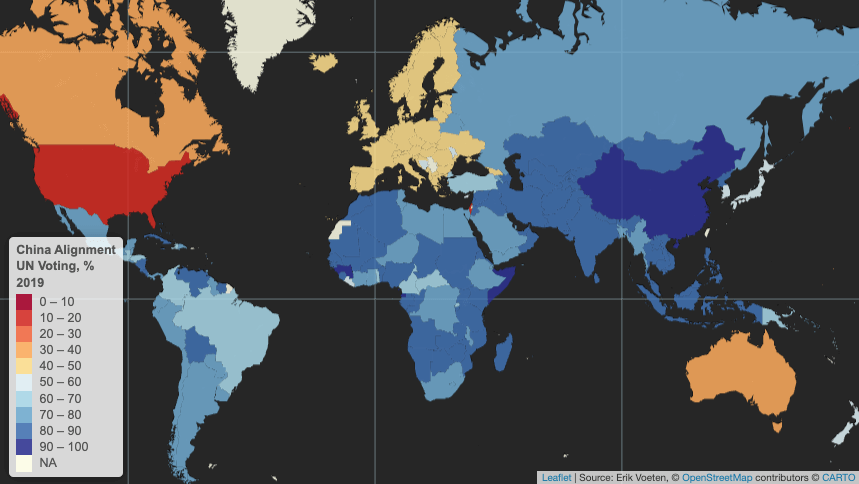

United Nations voting patterns

Yet emerging and developing economies as a whole are much more geopolitically-aligned with China than they are with the US. Using the latest available data on countries’ voting patterns in the United Nations’ General Assembly, in 2019 only a few EMDEs voted in alignment with the US more than 20% of the time. None did so in more than 50% of votes.

In contrast, EMDEs tend to vote in lockstep with China, which, after all is still considered somewhat of an emerging market itself. Virtually no EMDE votes outside of Europe were misaligned with China in the UN more than 50% of the time in 2019. Geopolitics is of course more complex than suggested by UN voting, and the world is not reverting to Cold War-era bipolarity, with multipolarity seemingly emerging on the horizon instead.

Walking a tightrope

Nevertheless, the above data suggests that sovereign borrowers are navigating a complex environment in which they have to walk a tightrope between managing relationships with Chinese creditors and maintaining access to IMF support and lending from the Paris Club and private creditors. As such, some EMDE governments may not see that it is in their best interests to ask their largest creditors, which are often Chinese, to take steep haircuts during debt resolutions as has often been the case with past Paris Club restructurings and the Common Framework.

Instead, countries in debt distress may prefer to ask China for maturity extensions and for maintaining exposure while they implement structural reforms to set debt on a more sustainable path. This approach has the potential drawback of conflicting with or delaying IMF program negotiations, which typically require financing assurances from key creditors. Even so, some sovereign borrowers – especially those that are among Beijing’s strategic partners – may judge that their relationship with China is more important in terms of resources than IMF program sizes.

Still others may prefer to rely more on the G20’s Common Framework and the IMF and World Bank. This is especially true considering that Chinese lending to EMDEs has slowed to a trickle over the past five years as Beijing reconsiders its Belt and Road Initiative ambitions.

A poorly-functioning global trading system

Yet the drawback of relying on G7 countries and the Anglosphere for sovereign lending is that, ultimately, among these only Germany and Japan run meaningful current account surpluses. And while bilateral aid from the G7 is non-negligible, external deficits in the US, UK, Canada, and (historically) Australia mean that global capital flows towards these countries rather than from them to the world, as is the case with China.

One way to increase capital flows from rich to poor countries would be for more rich countries to begin running current account surpluses, which would effectively overhaul the global trading system. This is a highly unlikely outcome over the short- and medium-terms, for many reasons but partly because doing so would affect the US dollar’s reserve currency status, the ability to weaponize the dollar via sanctions, and undermine the power of US banks. In these murky waters, it is a small wonder then that many EMDE sovereign borrowers will continue to prefer to hedge their bets by viewing China as at least as important as the IMF and other creditors combined.