I spent most of 2012 working in Gabon, a gem of a country well-endowed with some of the lushest rainforest on the planet, abundant natural resources – oil, manganese, wood – and a small population. Like many observers, I was aware of the concerns leading up to the August 2023 presidential elections as President Ali Bongo sought a third consecutive term, especially given the post-electoral violence in 2016.

Yet the military coup of August 30th still comes as a surprise because, in recent years, the military takeovers in Africa had largely been confined to the Sahel region: Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, Chad, and Sudan. There were two other recent putsches, one in Guinea, on the Sahel’s doorstep, and another one in Zimbabwe.

These countries have much lower income/capita and larger populations. Unlike Gabon, most of them are landlocked and have arid climates.1Guinea is neither landlocked, nor does it have an arid climate. Zimbabwe is also not as arid as the Sahel. So what do these countries have in common with Gabon? Plenty, whether their colonial pasts under France2With the exceptions of Sudan and Zimbabwe. or the nitroglycerin-like combination of weak institutions and ethnic divisions.

| Country | Coup d’Etat(s) date | GNI per capita – USD | Population – mn |

|---|---|---|---|

| 🇬🇦 Gabon | August 2023 | 7,540 | 2.6 |

| 🇳🇪 Niger | July 2023 | 610 | 25.3 |

| 🇹🇩 Chad | October 2022 & April 2021 | 690 | 17.2 |

| 🇧🇫 Burkina Faso | September & January 2022 | 840 | 22.1 |

| 🇸🇩 Sudan | October 2021 & April 2019 | 760 | 45.7 |

| 🇬🇳 Guinea | September 2021 | 1,180 | 13.5 |

| 🇲🇱 Mali | August 2020 | 850 | 21.9 |

| 🇿🇼 Zimbabwe | November 2017 | 1,500 | 16.0 |

My analytical fallacy was to think about the coups in the Sahel as some sort of wave with common drivers, which would have a bearing in other parts of Africa and beyond. Not so, or at least not beyond the Sahel where several weak, poor states having trouble coping with terrorist insurgents is a commonality. Rather than a wave of African coups with a shared set of narrowly-defined underlying causes, a version of the Anna Karenina principle applies: “Each unhappy country is unhappy in its own way.”

Moreover, it is good discipline to keep ethnicity front of mind when analyzing African politics, as this helps reveal some of the political forces at play that make each country unique. Even though ethnic factors are often of secondary importance, as in the case of Gabon, considering ethno-linguistic and cultural differences also provides contextual granularity that is often absent from English-language coverage of francophone Africa.

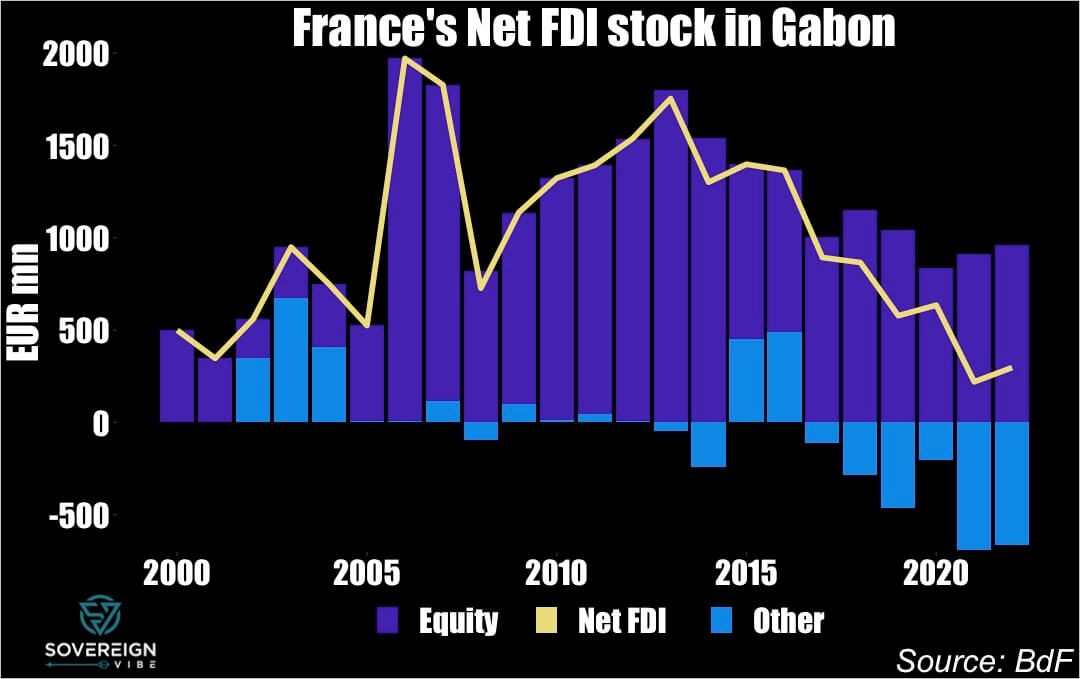

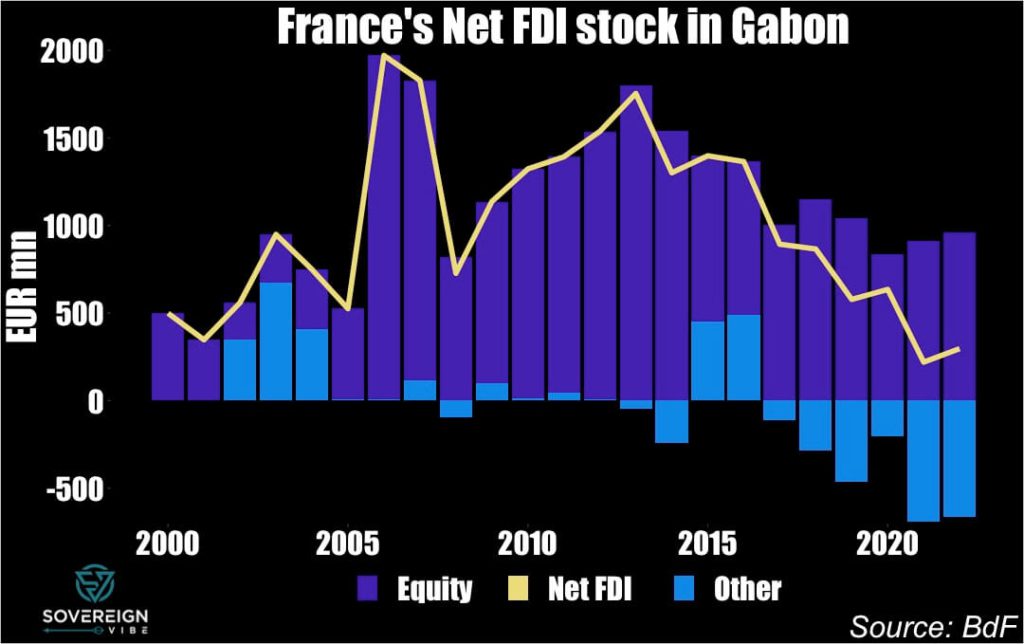

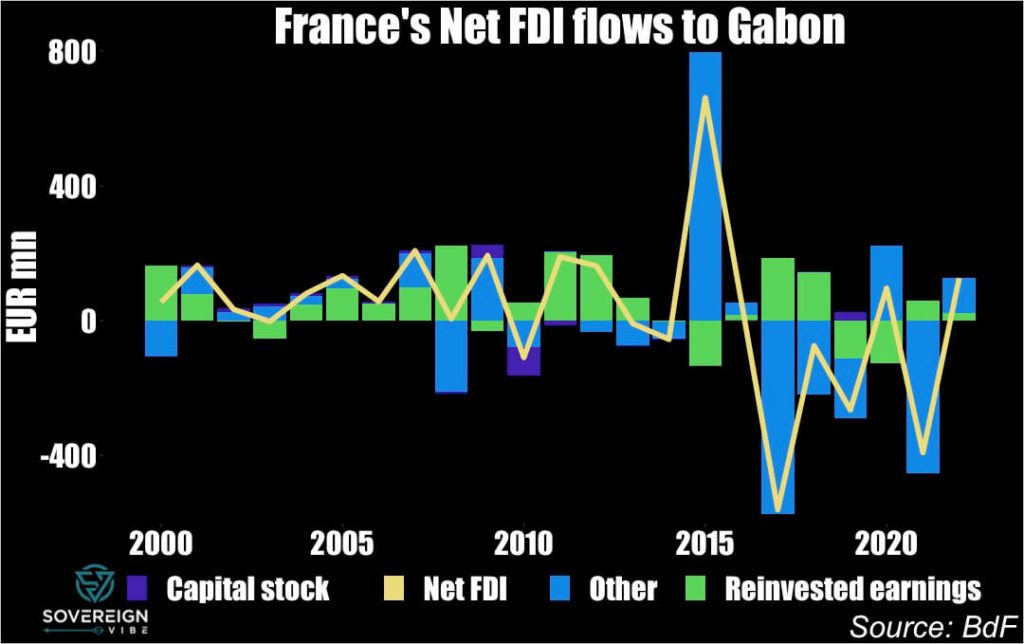

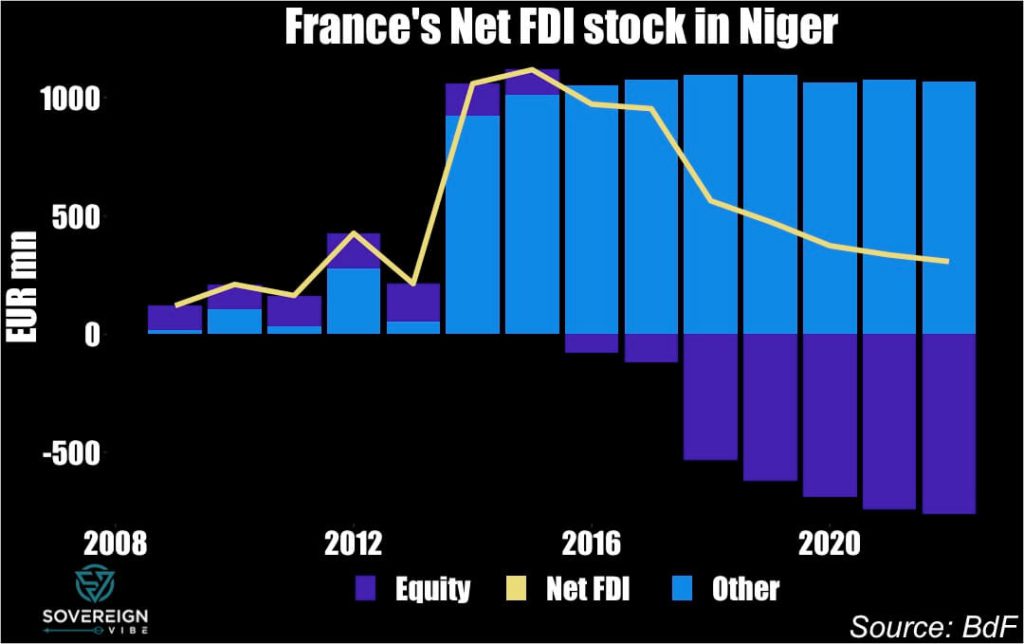

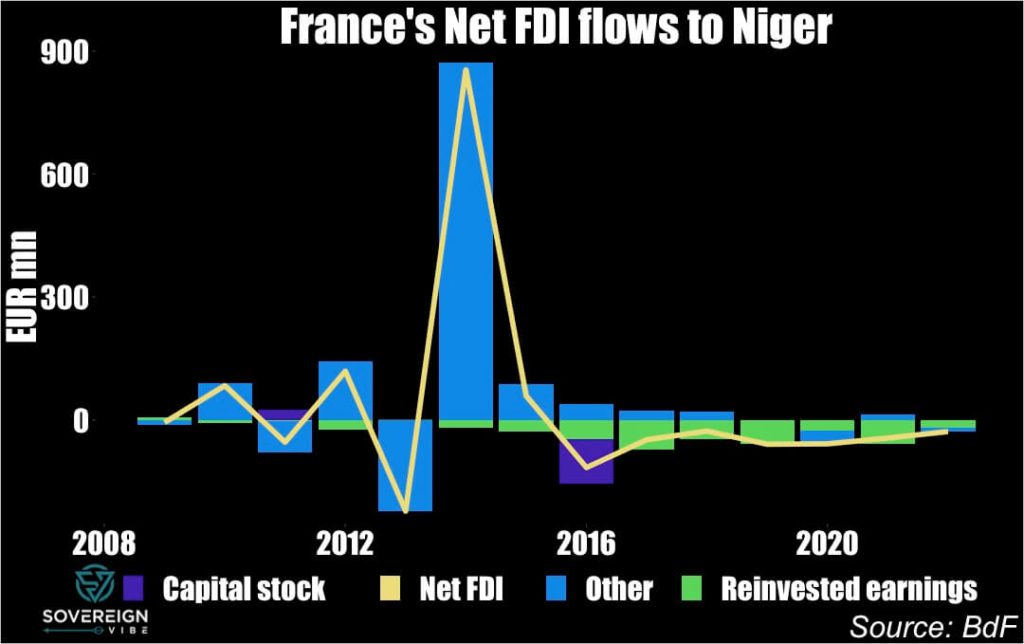

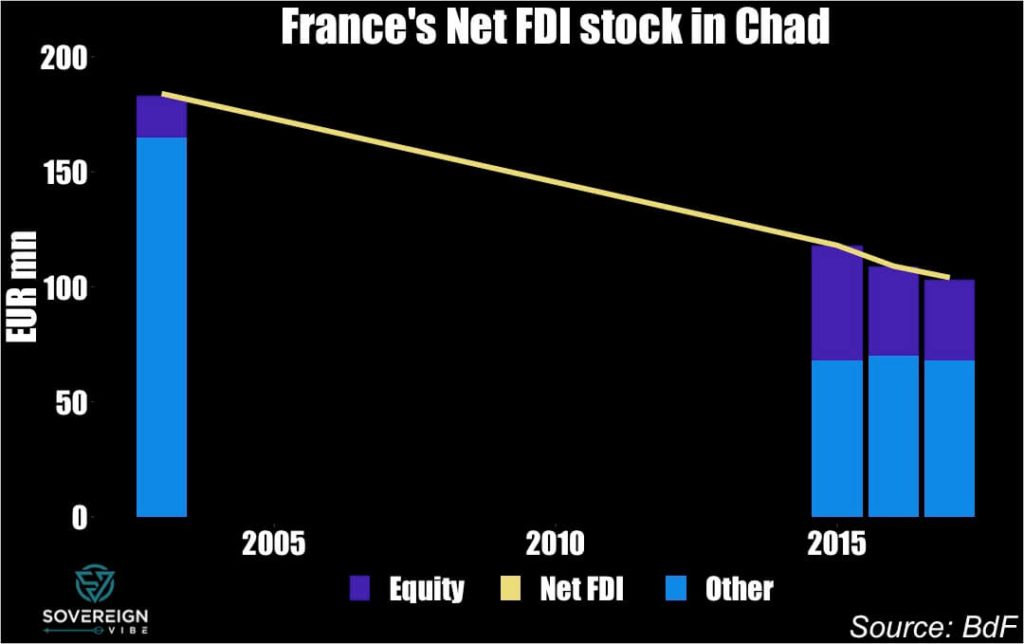

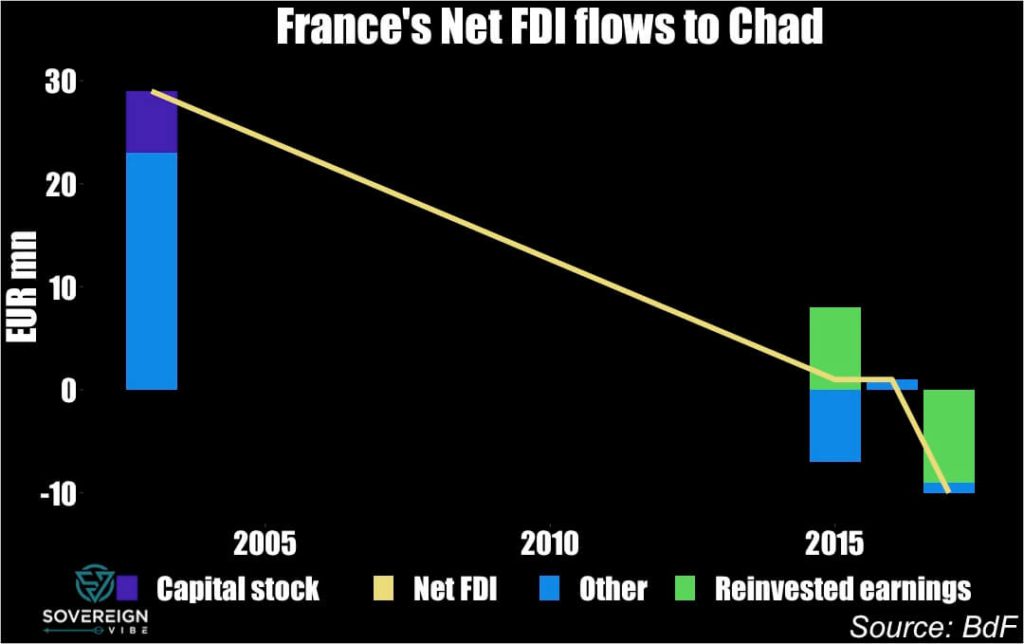

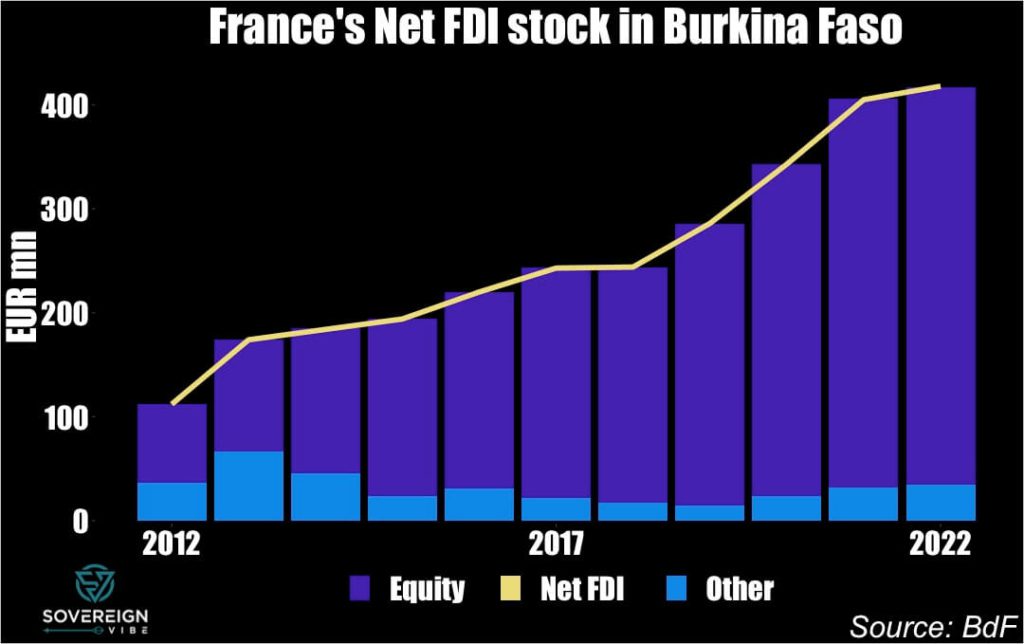

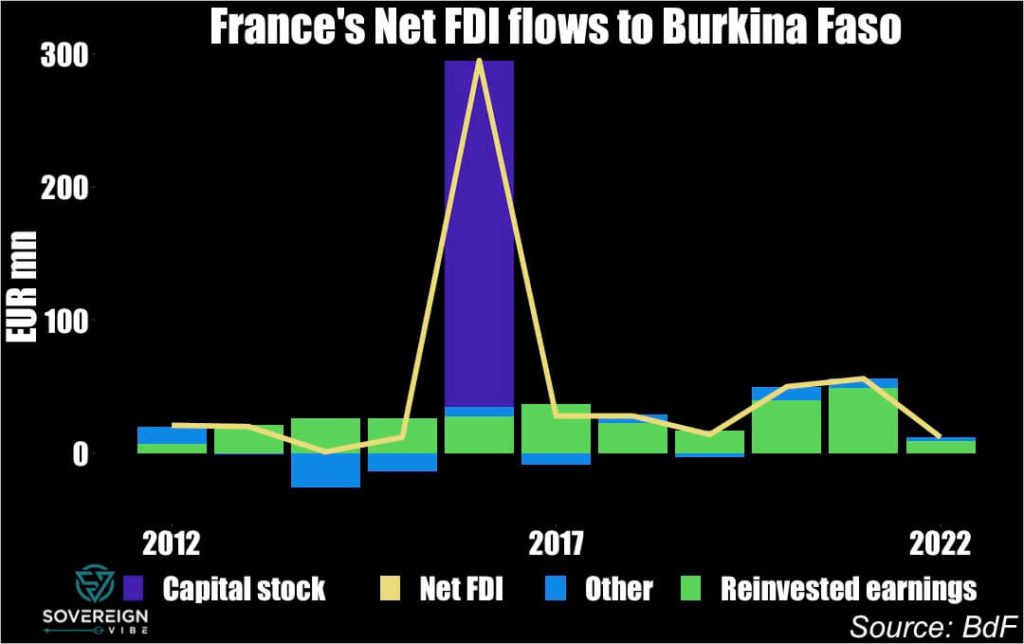

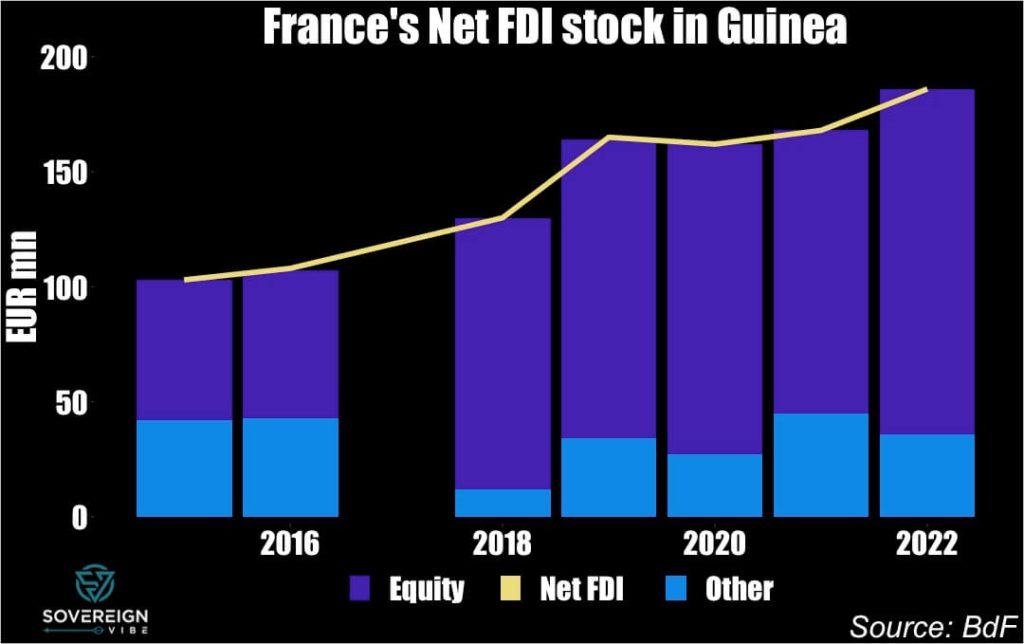

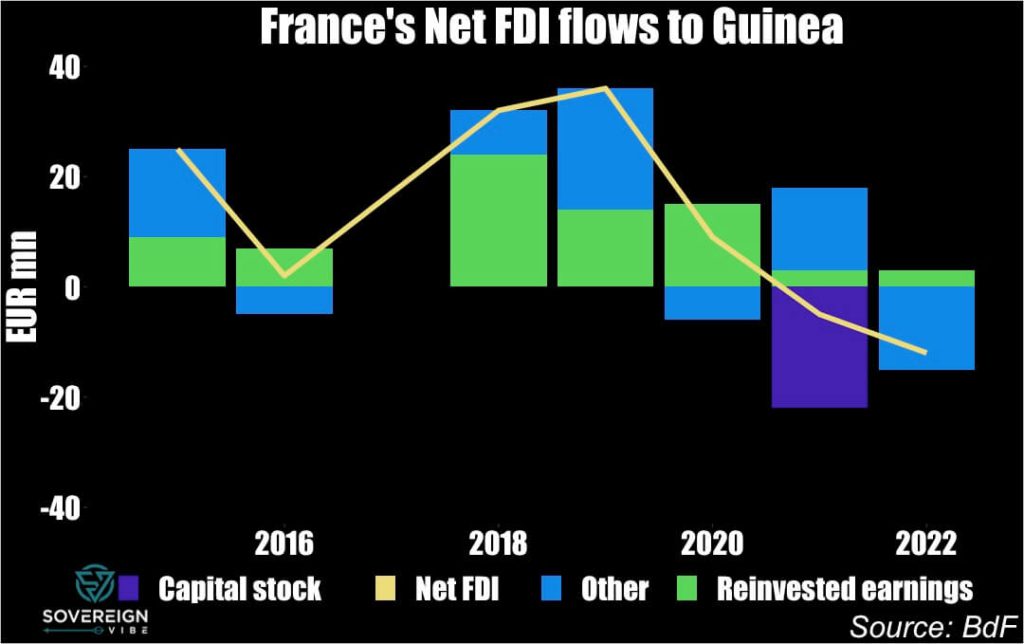

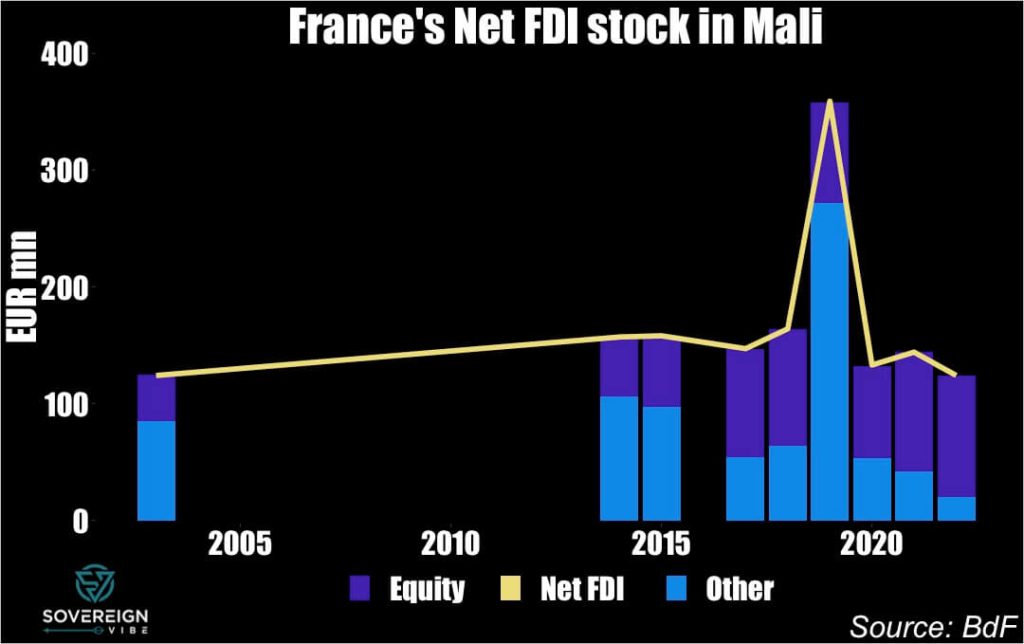

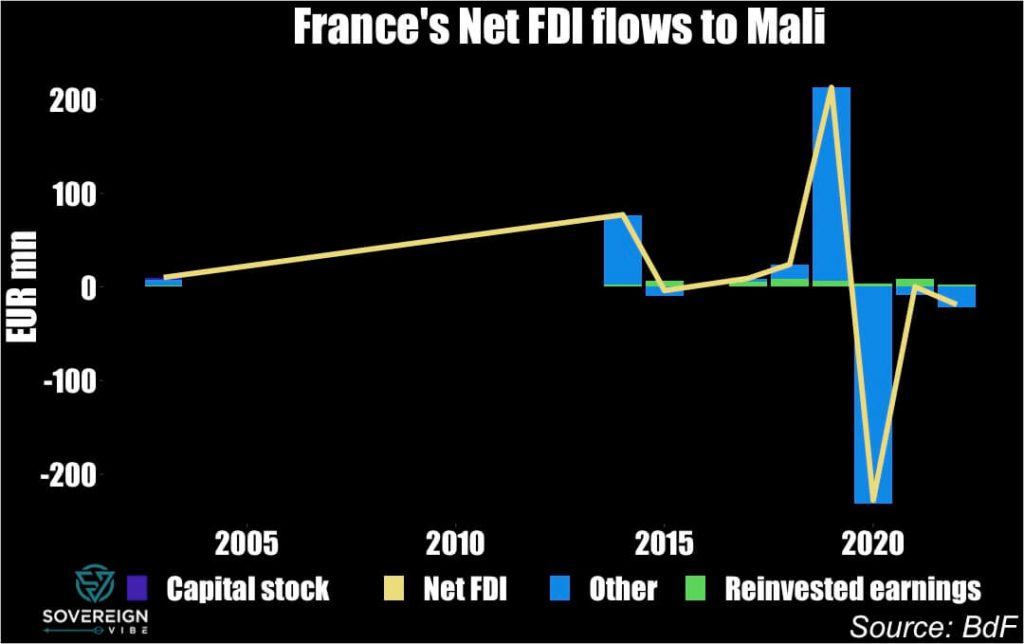

Below, I also provide charts on France’s net FDI to each of the francophone countries as a simple gauge of its ongoing involvement in each economy. This simple measure does not explain the coups in each country, nor does it encompass the complexity of the bilateral economic, political, and security relationships, but it provides relevant context as observers ponder Paris’s links to the continent.

🇬🇦 Gabon

August 2023: The military overthrows Ali Bongo, who hails from the small Téké ethnicity (~<10% of the population) in the remote Haut-Ogooué region, minutes after his electoral win is announced. The takeover appears to have elements of both popular dissatisfaction and of a palace coup. The leader of the junta, Brice Clotaire Oligui Nguema, was head of the Republican Guard’s special services unit. Also a Haut-Ogooué native, Nguema had long served under the previous president, Omar Bongo, before being sidelined for several years after Ali came into office.

- Omar Bongo had long relied on French support, while his son Ali had made some concessions to the larger Fang ethnicity (33% of the population) and others at various points during his terms.

- In Africa, only the Seychelles and Mauritius have higher GNI/capita than Gabon, where 1/3 of the population lives below the poverty line.

- Clearly, any wealth redistribution from the rapacious Bongo clan was insufficient for the population to allow him to continue pilfering the country indefinitely amid suspicions of electoral fraud in the current and previous elections.

- Enfeebled by a stroke in October 2018, Ali Bongo – and his reportedly dissolute family members – provided a complacent atmosphere at the presidential palace, thus combining with popular discontent to set the ideal conditions for Nguema and his co-conspirators.

- Of note, France’s net foreign direct investment stock in Gabon has been on a downward trend since the mid-2010s (see charts below), declining from around €1.8bn in 2013 to under €500mn in 2022. This is despite the global net FDI stock in Gabon rising over the same period, pointing to France’s diminished stature in the Gabonese economy. More detailed information on this topic will be available in future posts.

🇳🇪 Niger

July 2023: Junta leaders oust President Mohamed Bazoum, who is of Arab ethnicity ( < 0.5% of the population), purportedly for leniency towards islamist insurgents. This underscores the political importance of the security situation, as in several other countries throughout the Sahel.

- Bazoum succeeded Mahamadou Issoufou (Hausa, 55% of the population), who completed two terms as president without trying to run for a third term, instead nominating Bazoum as his preferred successor.

- Issoufou had himself come to power through elections a few years after a military coup ousted a previous president – Mamadou Tandja – who had attempted to stay on as president for longer than two terms, much like Ali Bongo in Gabon today.

- As in Gabon, France’s net FDI stock in Niger has been on the wane since the mid-2010s, declining from over €1bn to under €500mn as of last year. The entirety of French exposure to the country appears to in the form of debt and other instruments, including in all likelihood intra-company debt.

🇹🇩 Chad

April 2021 – October 2022: Long-serving President Idriss Déby (Zaghawa, ~1%) had taken power via a French-supported coup in 1990 against then-president Hissène Habré (Gorane, aka Daza or Toubou, ~4-5%) and was fatally wounded in April 2021 during hostilities with insurgents, mainly of Gorane extraction.

- Déby’s son Mahamat Idriss Déby (half Zaghawa, half Gorane, married to a Gorane, father of nine children) seized control of the country at the head of a military junta immediately after his father’s death with a commitment to an 18-month transition period to culminate in elections, which he postponed by two years in October 2022.

- Despite limited French net FDI exposure to Chad, even here France’s presence is declining, from nearly €200mn in the early 2000s to around €100mn today.

🇧🇫 Burkina Faso

September 2022: Captain Ibrahim Traoré (b. 1988) overthrew Lieutenant-colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba for not having followed through on the promises of the January 2022 coup and following several deadly terrorist attacks, notably in Gaskindé, where jihadists ambushed a provisioning convoy, resulting in at least 11 deaths.

- Mutineering soldiers ousted President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré (Mossi, ~56%) in January 2022 following a crushing defeat of burkinabè armed forces by jihadists in November 2021, amid widespread disappointment at the government’s management of the conflict and failure to provide rations to troops. Lieutenant-colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba succeeded Kaboré as transitional president.

- In October 2014, a popular uprising ousted then-president Blaise Compaoré’s (Mossi, ~56%) upon his attempt to change the constitution and thereby allow himself to stand for a fifth term after 27 years in power. After a year of transition, Kaboré was elected president in November 2015.

- In constrast to Gabon, Niger, and Chad, France’s net FDI stock in Burkina Faso has been rising steadily for the past decade, driven mainly by reinvested earnings into increasing shareholder equity. Overall exposure has jumped from ~€100mn in 2012 to ~€400mn in 2022.

🇸🇩 Sudan

April 2019 & October 2021: General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan seized power in 2021, placing Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok under house arrest. The Sudanese Armed Forces ousted the long-reigning Omar al-Bashir in 2019 under the leadership of Ahmad Awad Ibn Auf.

🇬🇳 Guinea

September 2021: Amid widespread popular dissatisfaction with the government, military putschists arrested President Alpha Condé (Mandingo aka Malinké, 23%, second-largest group) as special forces commander Mamady Doumbouya dissolved the government and seized power as interim president. Of these recent coups, the Guinean case most closely resembles the current situation in Gabon.

- France’s net FDI exposure to Guinea has been rising steadily since the mid-2010s, albeit from a low base, partly reflecting Conakry’s historically relatively cool relations with Paris. Up from €100mn in 2015, French FDI stock stood at ~€175mn in 2022.

🇲🇱 Mali

August 2020: A colonel in Mali’s special forces, Assimi Goïta (Minianka, ~7%, b. 1983) has been the country’s de facto leader since a successful coup ousting IBK in August 2020.

- Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta (Mandingo, aka Malinké or Maninka, ~8%, d. 2022) is elected president in 2013 after the elections were delayed by a year, following the military putsch of 2012 and the ongoing war against islamist insurgents. He rejected the coup but agreed to negotiate with the junta, which adopted a neutral position towards him. In 2020, after months of political crisis stemming from economic pressures, the Peul/Fula-Dogon ethnic conflict, and the pandemic, a coup removed IBK from power.

- Amadou Toumani Touré (Bambara, ~25%, largest group, d. 2020) was president from 2002-2012 after having been elected democratically and later ousted via military coup two months before the 2012 elections, in which he was not running. The coup was to denounce the management of the conflict in northern Mali between the army and the Touareg rebellion at the time. He had himself participated in a coup d’Etat in 1991 against the then-long-standing president Moussa Traoré (Malinké, ~8%, d. 2020).

- France’s FDI exposure to Mali has essentially moved sideways over the past 20 years, standing at around only €100mn.

- 1Guinea is neither landlocked, nor does it have an arid climate. Zimbabwe is also not as arid as the Sahel.

- 2With the exceptions of Sudan and Zimbabwe.