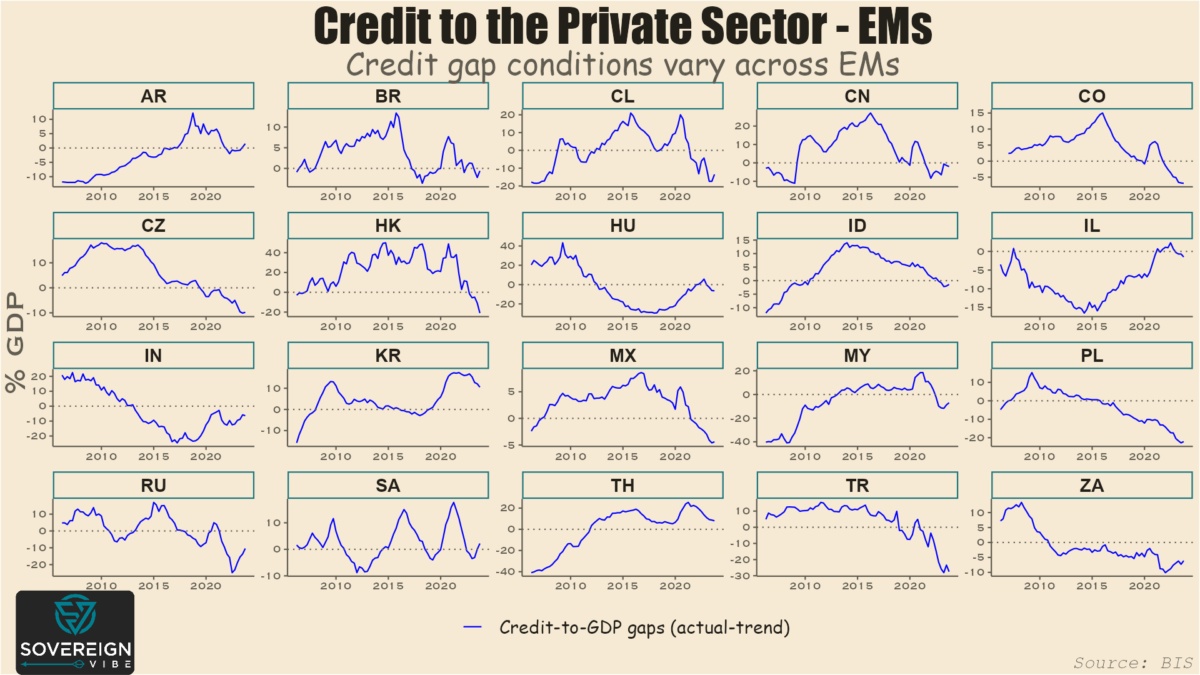

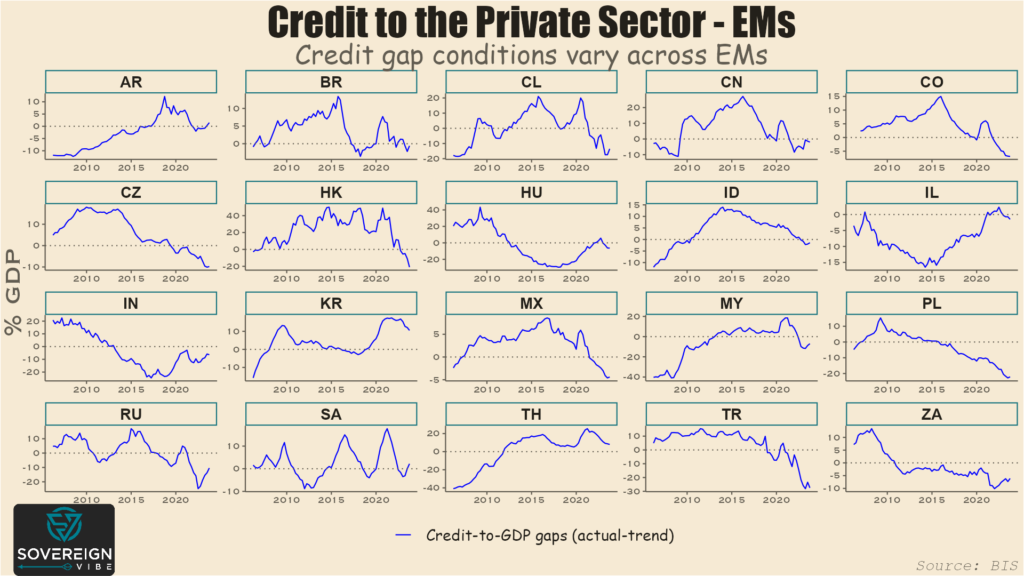

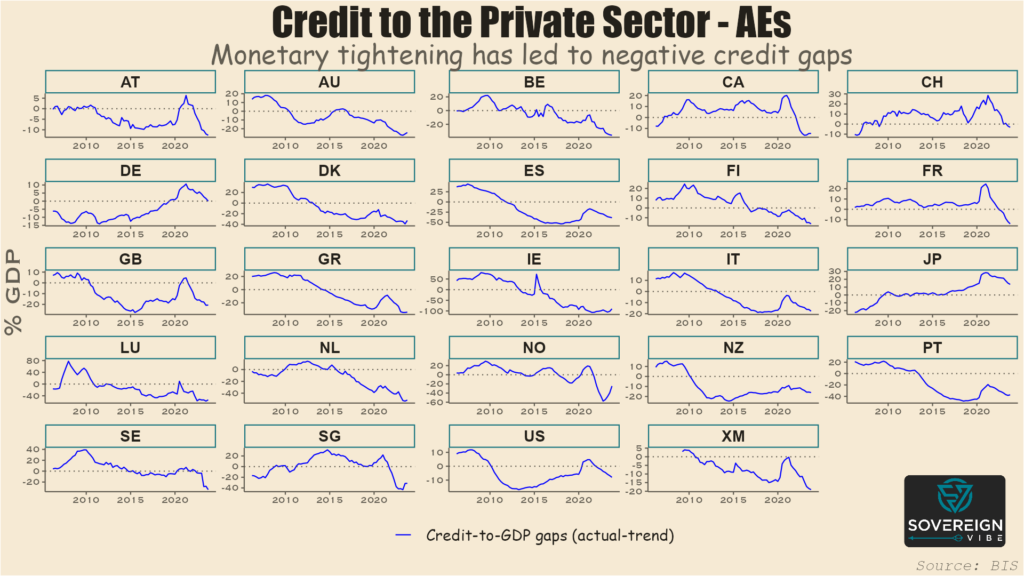

Today’s charts are snapshots of credit-to-GDP gaps in emerging and advanced economies. As a reminder, the credit gap measures the difference between actual credit to the private sector and trend credit to the private sector.

These estimates through Q3 2023 are provided by the Bank for International Settlements, which describes its credit-to-GDP ratio as capturing total borrowing from all domestic and foreign sources by the private non-financial sector.

Several factors have an impact in determining private sector borrowing. These include how developed the country’s financial system is, the ability of domestic firms to borrow internationally, and the extent to which public sector borrowing crowds out the private sector.

As such, the level of credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP varies significantly from country to country. It is therefore more helpful to look at credit-to-GDP gaps when comparing across countries.

Besides, credit gaps are one measure that the IMF uses in measuring sovereign stress for market-access countries. A high, positive credit gap can point to the presence a credit bubble. Such bubbles are sometimes a symptom of macroeconomic imbalances and policies that can lead to sovereign debt strains.

There is little evidence of excessive credit gaps in emerging markets. The absence of credit bubbles is at least partly attributable to EM central banks hiking rates rapidly in response to inflation when it first began appearing in the latter stages of the pandemic. This early tightening has enable EM central banks to start easing before many of their developed market peers, e.g. Brazil and Mexico in Q1-2024.

Of course the chief objective of monetary policy is price stability. But, by definition, rate changes also affect credit conditions and lending.

South Korea is one of only two EMs in this sample with a sizable, positive credit gap. That excess credit is, however, declining, as the country’s central bank maintains its policy rate at a 15-year high with no signs of imminent loosening.

The other is Thailand, where the central bank is holding its policy rate steady despite political pressure to ease. In the meantime, its credit gap is also narrowing.

This relatively benign outlook across major EM is a sign of improving policy credibility compared to the volatility that led to various EM financial crises in the past. On the other hand, a negative credit gap doesn’t necessarily indicate sound macroeconomic management, e.g. see Turkey, South Africa etc.

The BIS only provides data for 21 EMs, which is already a lot. But achieving broader country coverage is why I also use similar World Bank data in my sovereign stress analysis.

Looking at advanced economies, the gaps are virtually all negative, as in EM. But, unlike EM, almost all of the gaps appear to still be widening, representing the later start to post-pandemic monetary policy tightening by AE central banks.

Note the sizable negative gap in the Euro Area (i.e. “XM”), which is a cyclical indicator suggesting that a turning point for the ECB might not be too far off. Indeed, Switzerland has recently led the way with a first DM rate cut this cycle. Japan is the outlier with its large, positive credit surplus, but tighter monetary policy has been eroding that gap in recent quarters.