Higher for (a bit) longer, but don’t buy into inflationista hype.

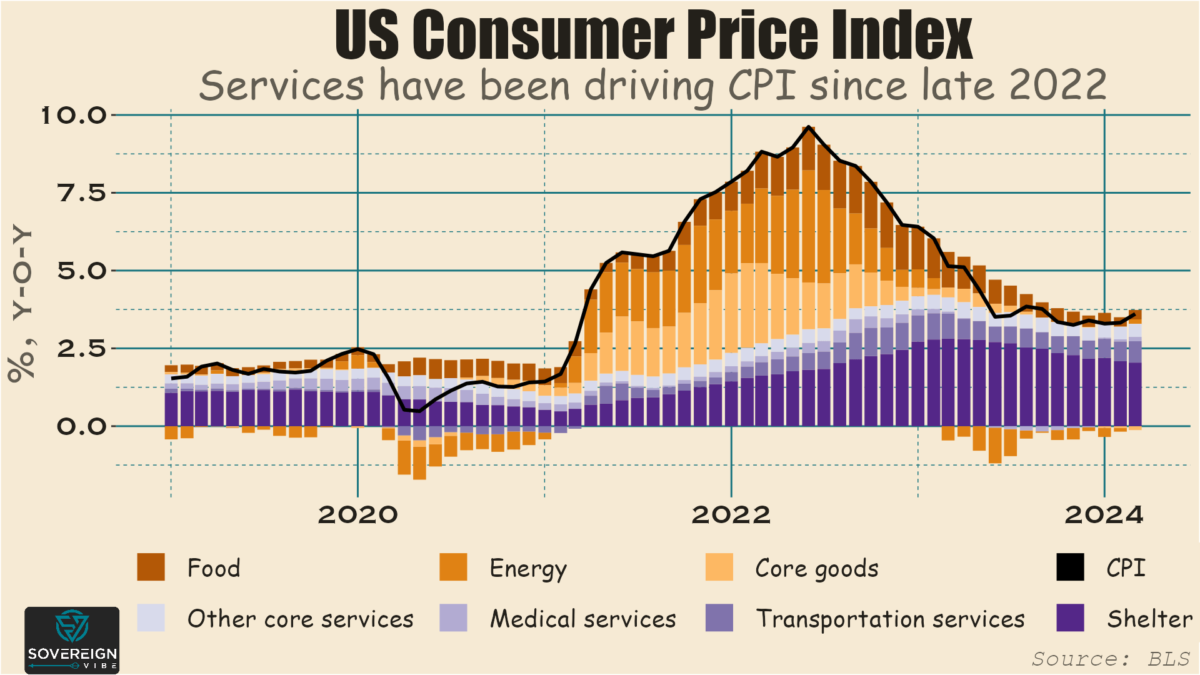

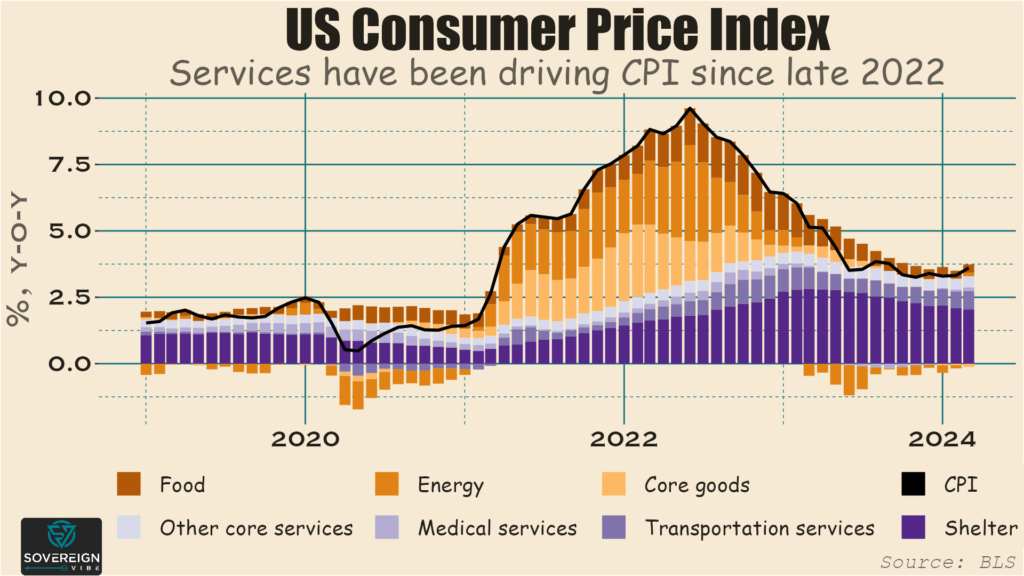

I wrote recently that emerging market sovereigns considering new issuance should be ready for Federal Reserve rate cuts in 2024, despite the hot Q1 inflation prints. The point is that core goods inflation has all but disappeared from the consumer price index and that core services inflation is concentrated in the transportation services segment, particularly motor vehicle insurance. The rise in car insurance costs in the US is a structural change, and the base effect will be locked in before long.

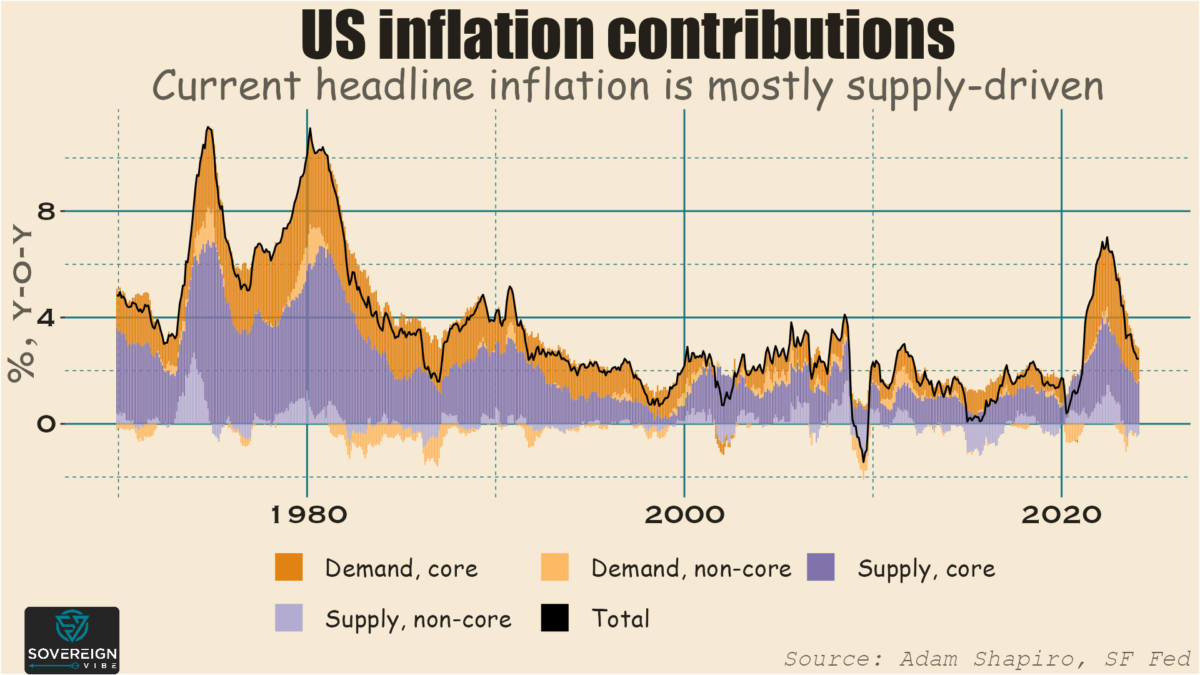

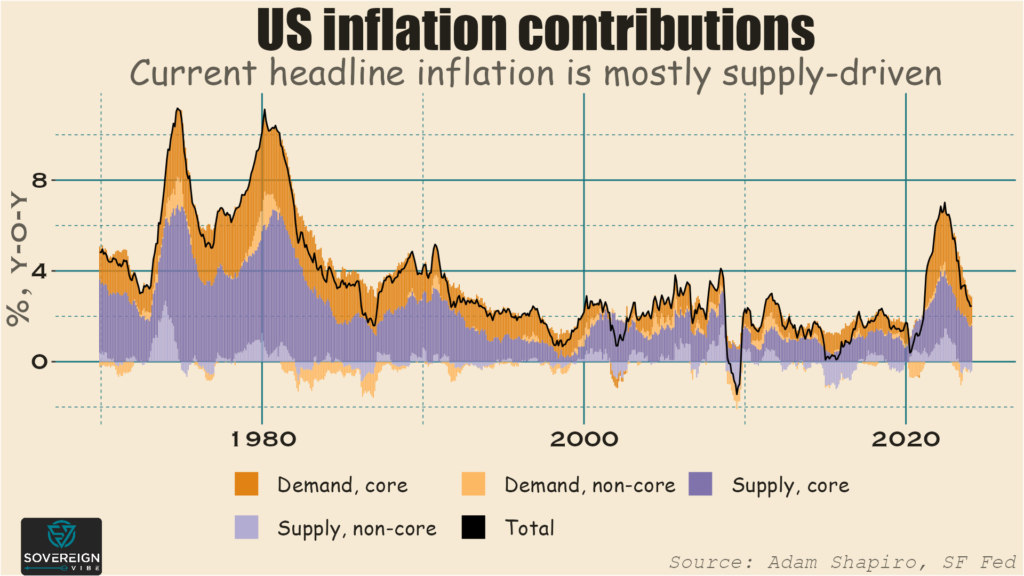

This inflation stickiness in transportation services is a lingering effect of Covid supply chain disruptions. Although these have lasted longer than most expected, they won’t last forever and will be resolved eventually. Juxtapose that point with data out of the San Francisco Fed that measures volume dynamics to gauge whether price rises are supply- or demand-driven. Supply is currently driving inflation, which confirms the CPI narrative around motor vehicle services.

This week of course Jerome Powell signaled that rates would be staying higher for longer. This makes good sense given higher Q1 inflation following his (overly) dovish remarks in December that markets interpreted (too) exuberantly.

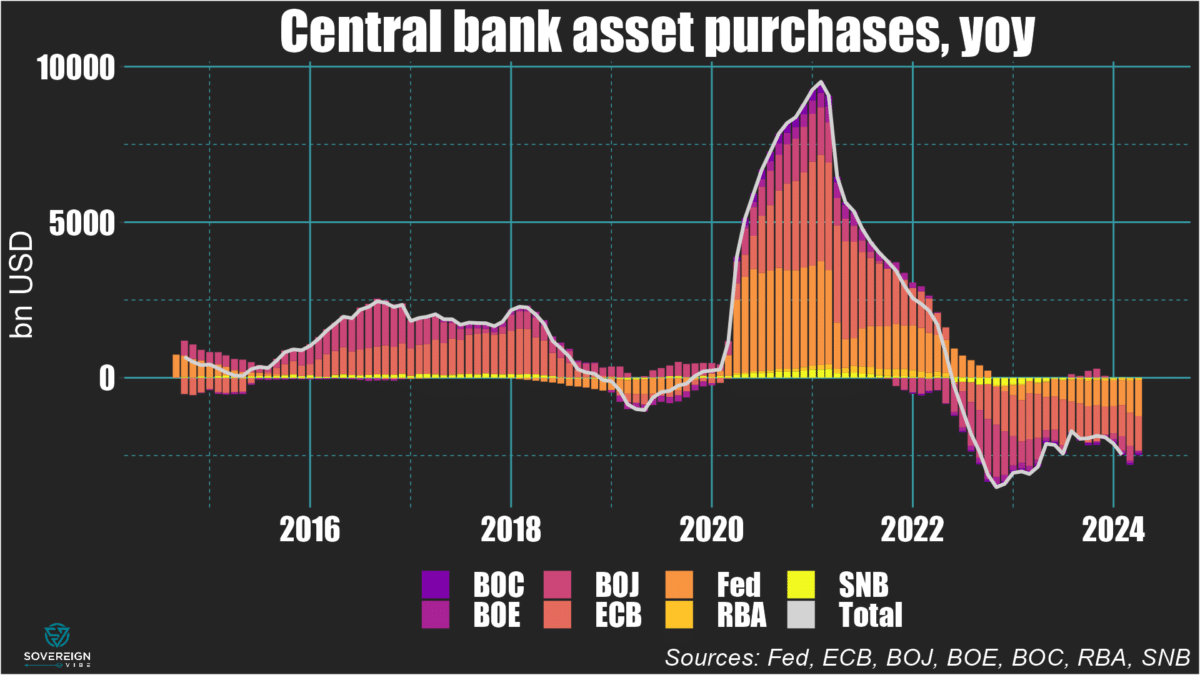

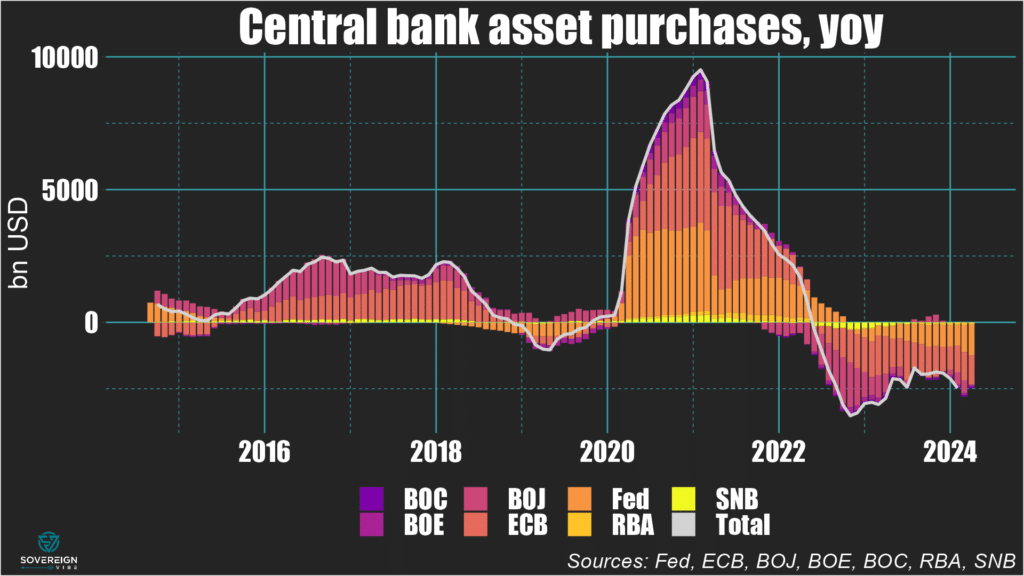

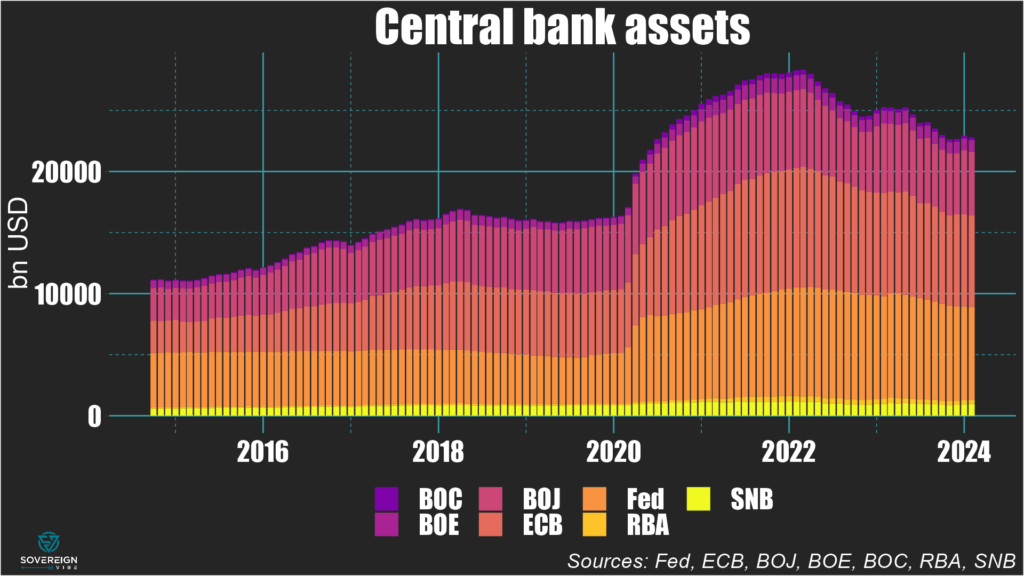

One-to-two rate cuts are still priced in for this year, and any talk of new rate hikes are overblown. Powell himself said this week that a rate increase would be “unlikely.” Moreover, the Fed is slowing down its quantitative tightening program, lowering the monthly cap on US Treasuries it rolls off its balance sheet from $60bn to $25bn. So rates may be higher for longer than expected amid all the December-January euphoria, but the wind is still blowing in an “easing” rather than in a “tightening” direction.

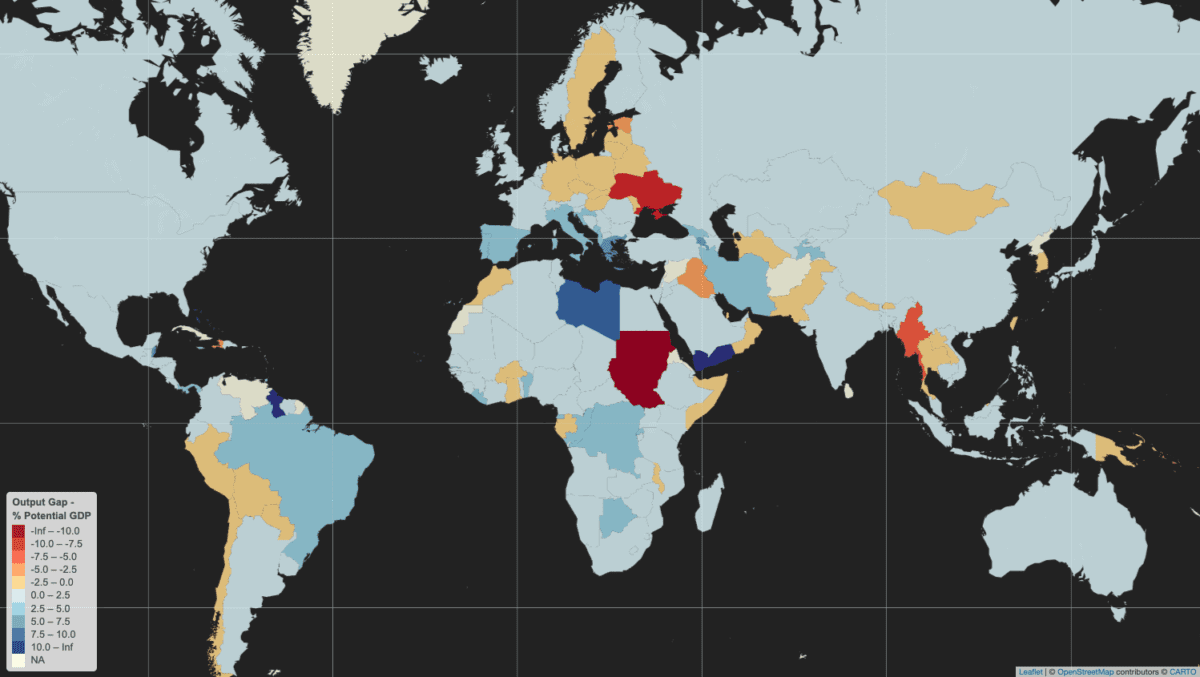

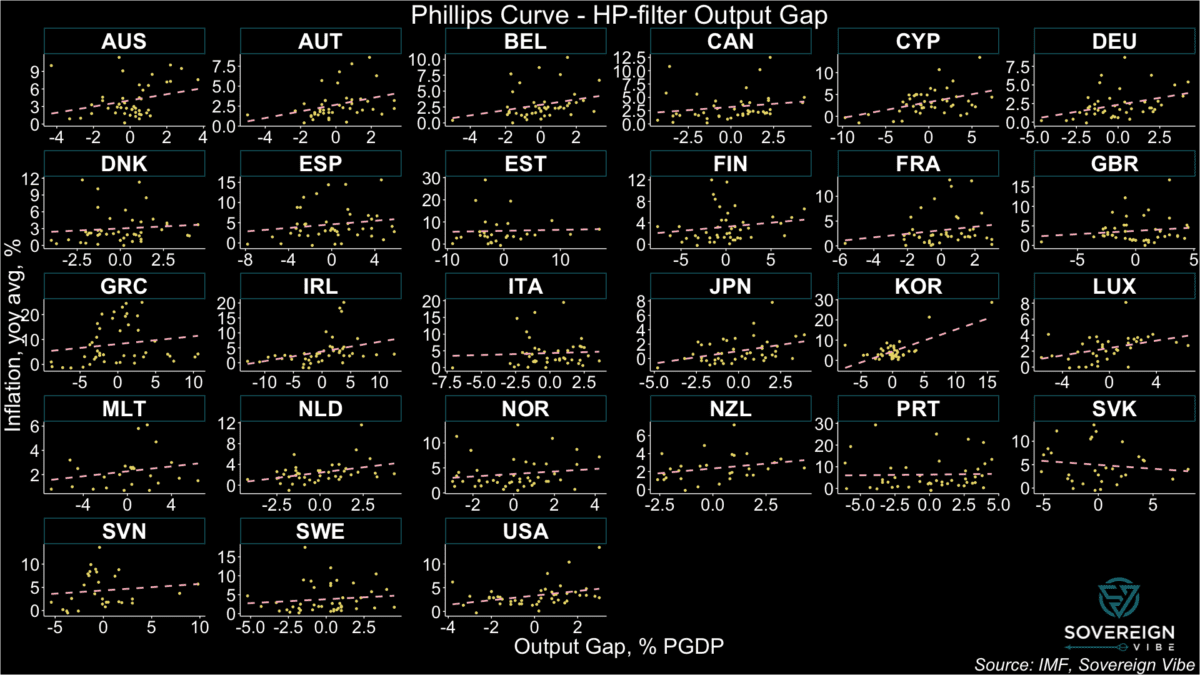

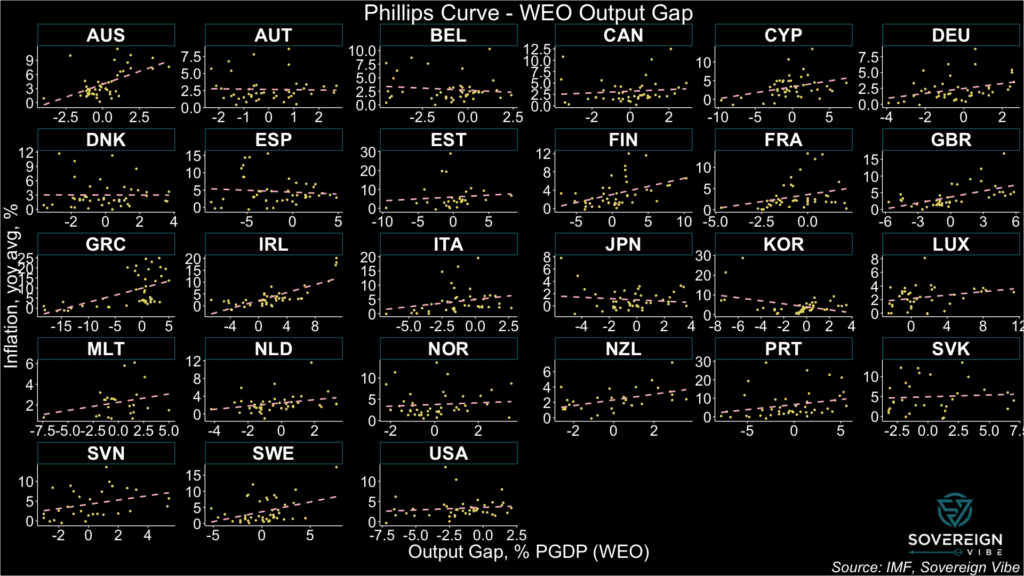

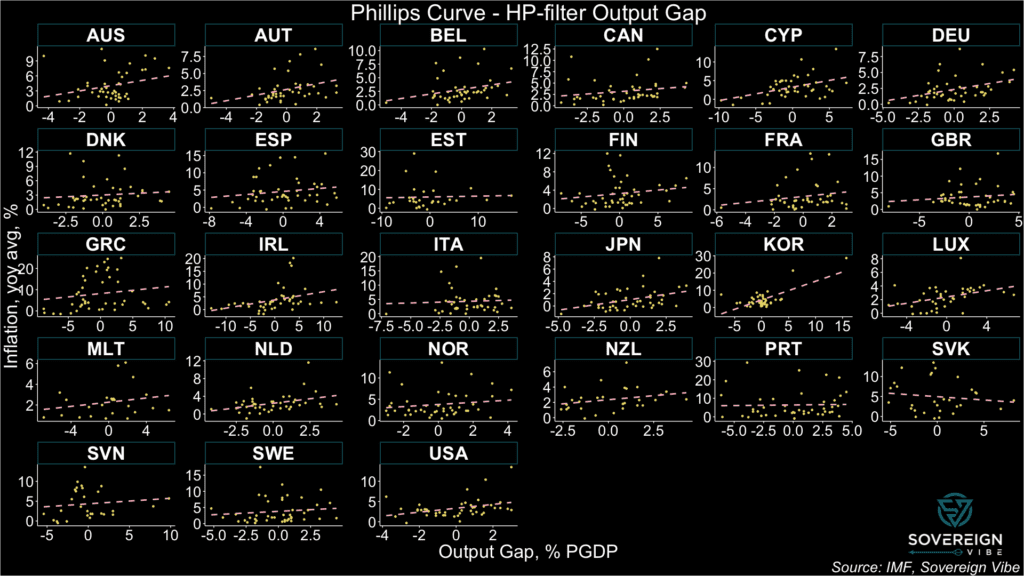

There are other reasons that declining inflation and lower rates are likely in store later this year. Monetary policy has a lag time, so the restrictive stance that has been in place for the past few years will continue to work through the economy. There is also a post-Covid negative potential GDP trajectory gap, a point that my former colleague Robin Brooks makes. In fact, I’m hardly alone on this: see Claudia Sahm on the Covid hangover and Brian Levitt of Invesco on transportation services.

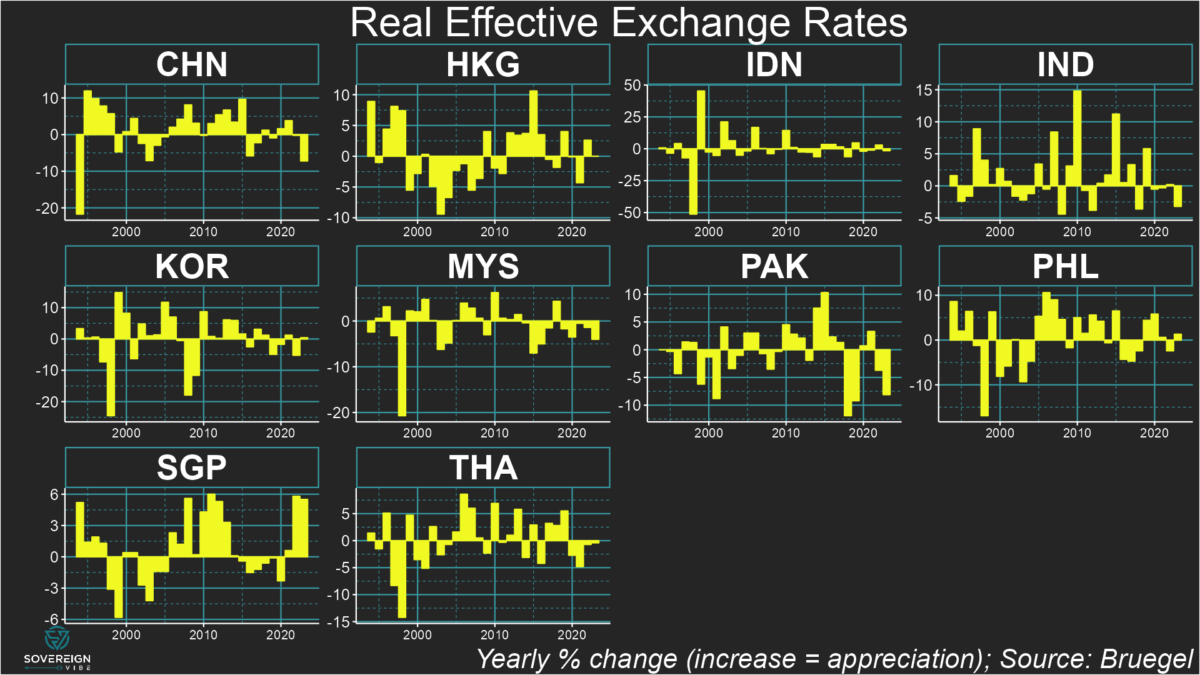

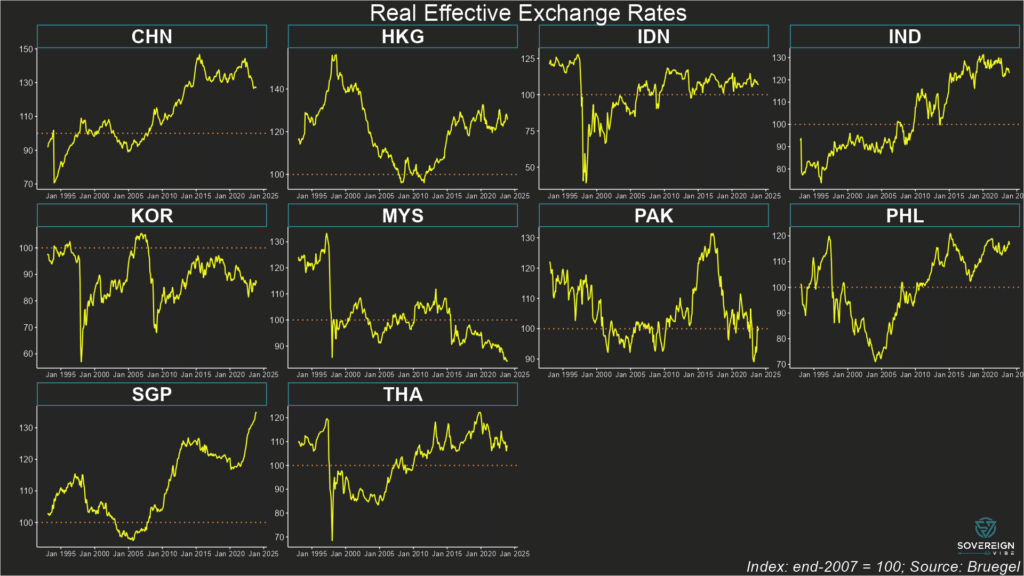

I’ll get back to more of a direct focus on emerging markets next week, but it’s important for EM watchers to keep an eye on the elephant in the room as well. Those developed market policy rates tend to have statistically significant negative relationships with capital flows to and from EM. Besides, Sovereign Vibe is also about global macro!