One of the major announcements at last week’s World Bank/IMF Spring Meetings concerns the unsustainable rise in US government debt. While it’s old news that the budget deficit is large – $1.7tn / 6.3% of GDP in 2023 and a projected $1.6tn in 2024, I want to highlight how US debt relates to the the role of the dollar internationally. Besides, the Springs also mean there is new IMF WEO data to play with:

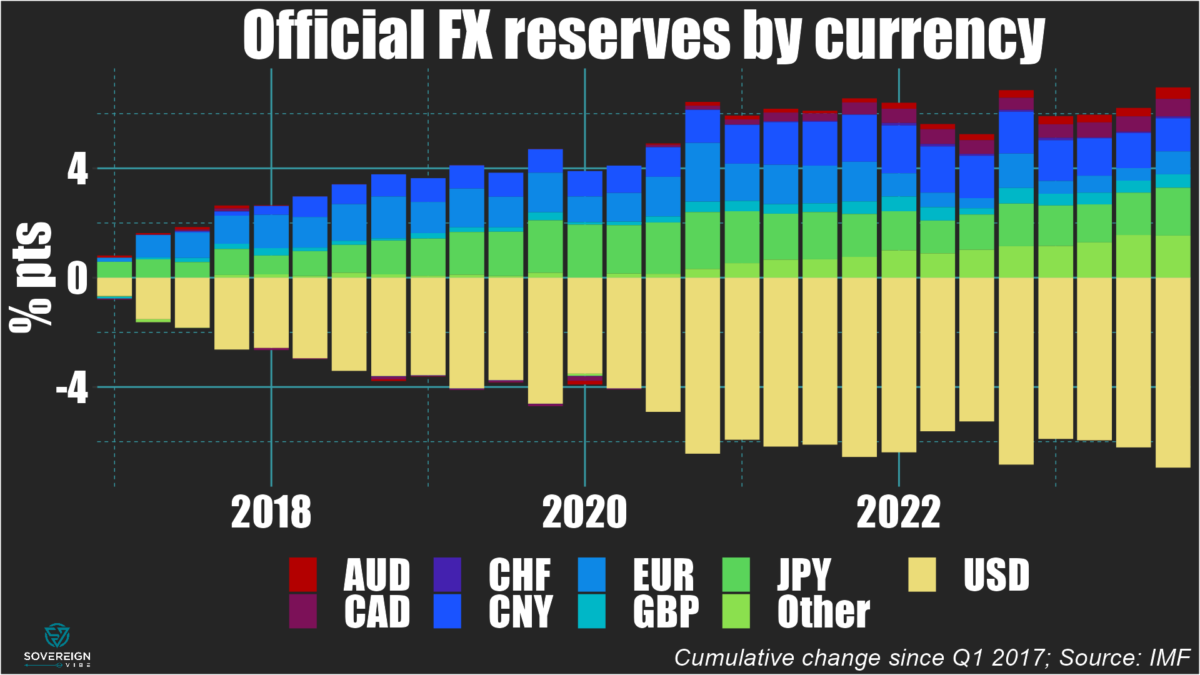

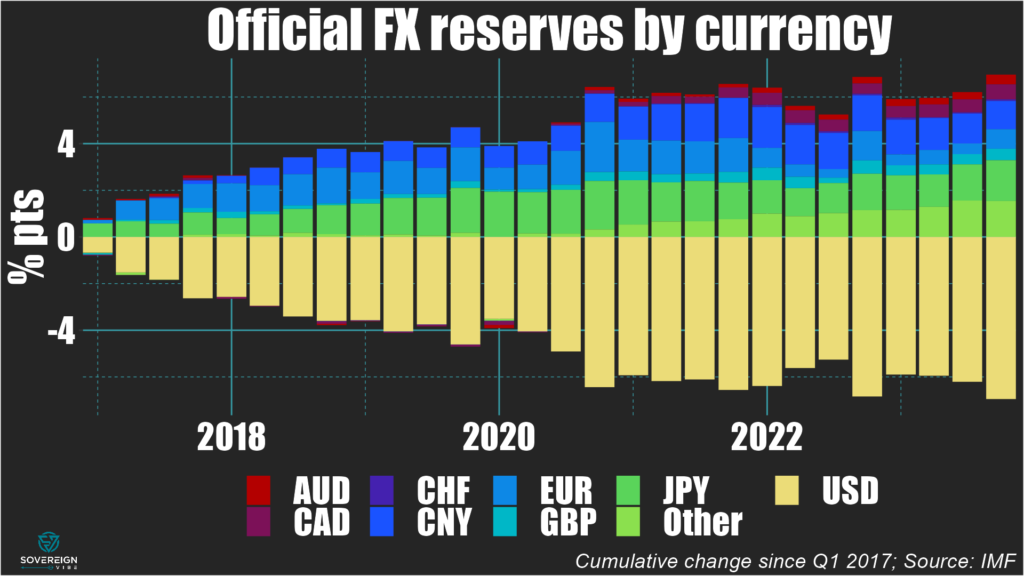

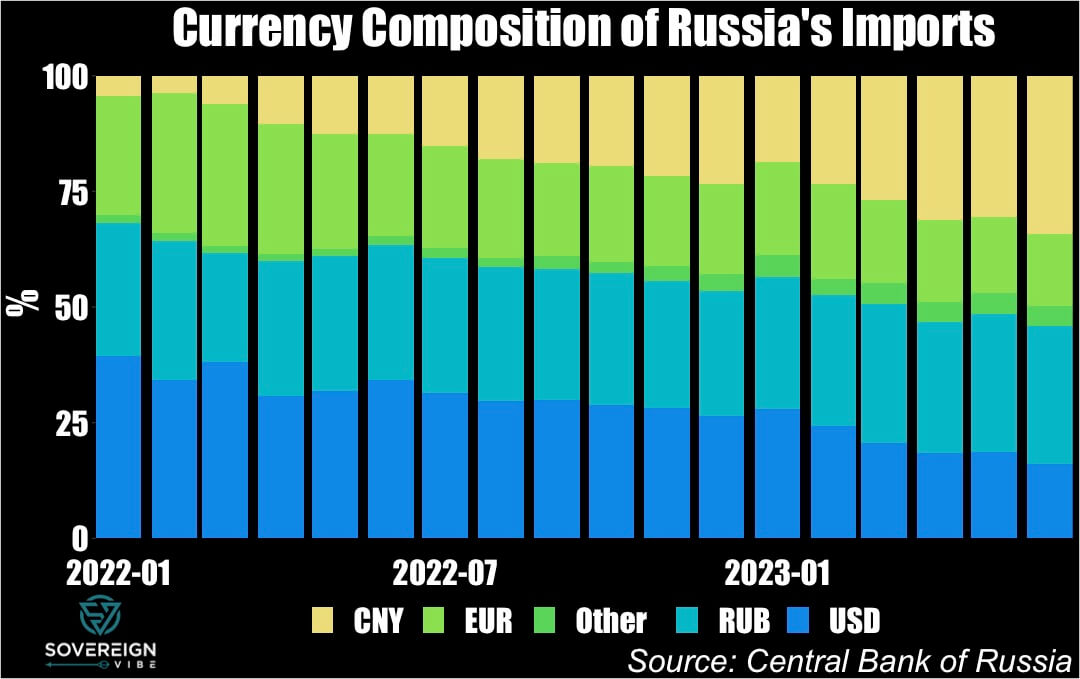

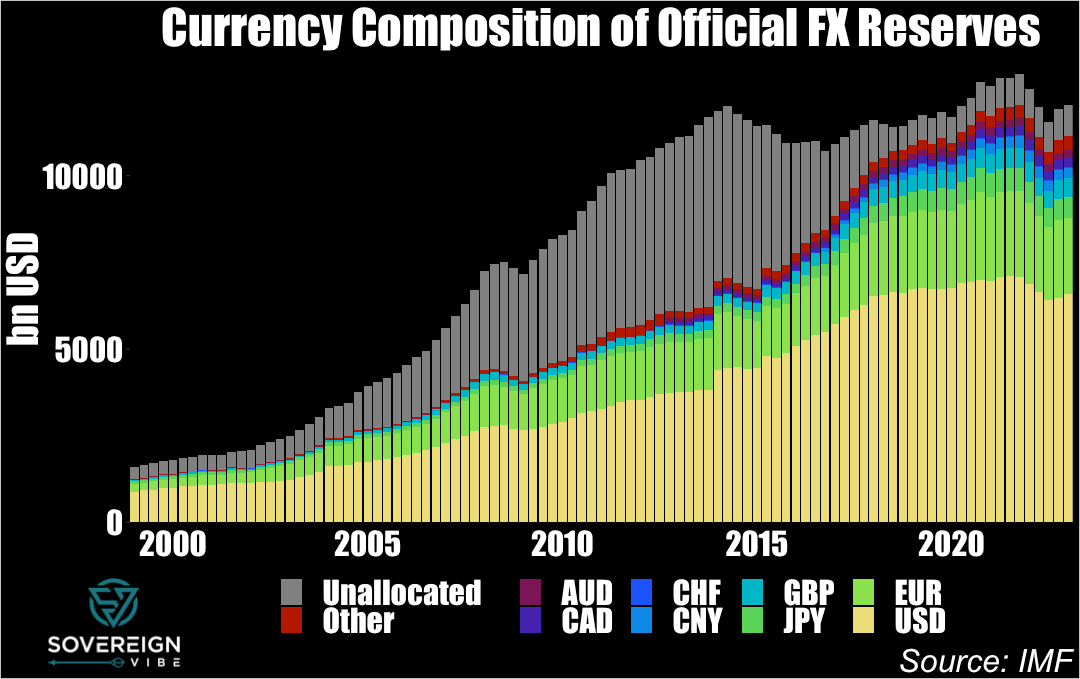

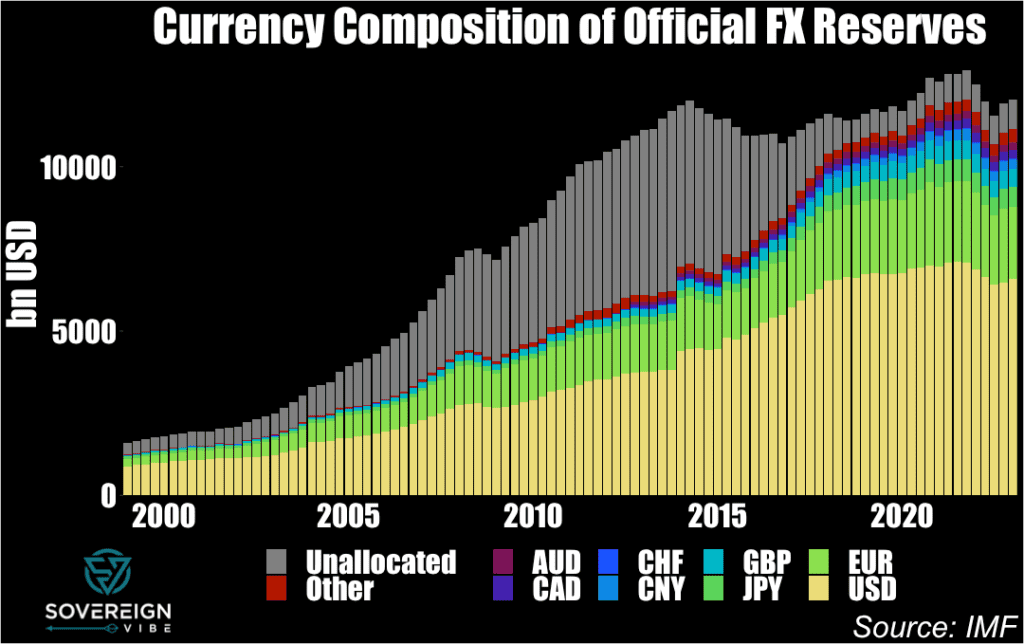

De-dollarization has become a hot topic in recent years, with many observers siding ideologically “against” the USD, e.g. Brazil’s president Lula asking why international transactions should occur in dollars. Many also claim that the yuan and other BRICS currencies are rising in importance. While it’s true that RMB is playing a greater role in trade invoicing and international reserves, this increase is limited to either specific countries (e.g. Russia) or has been less than the rising prominence of other G7 currencies.

Yet such grandstanding belies ignorance of why the greenback is so dominant. China scholar and Carnegie Endowment fellow Michael Pettis explains this with his usual brilliance.

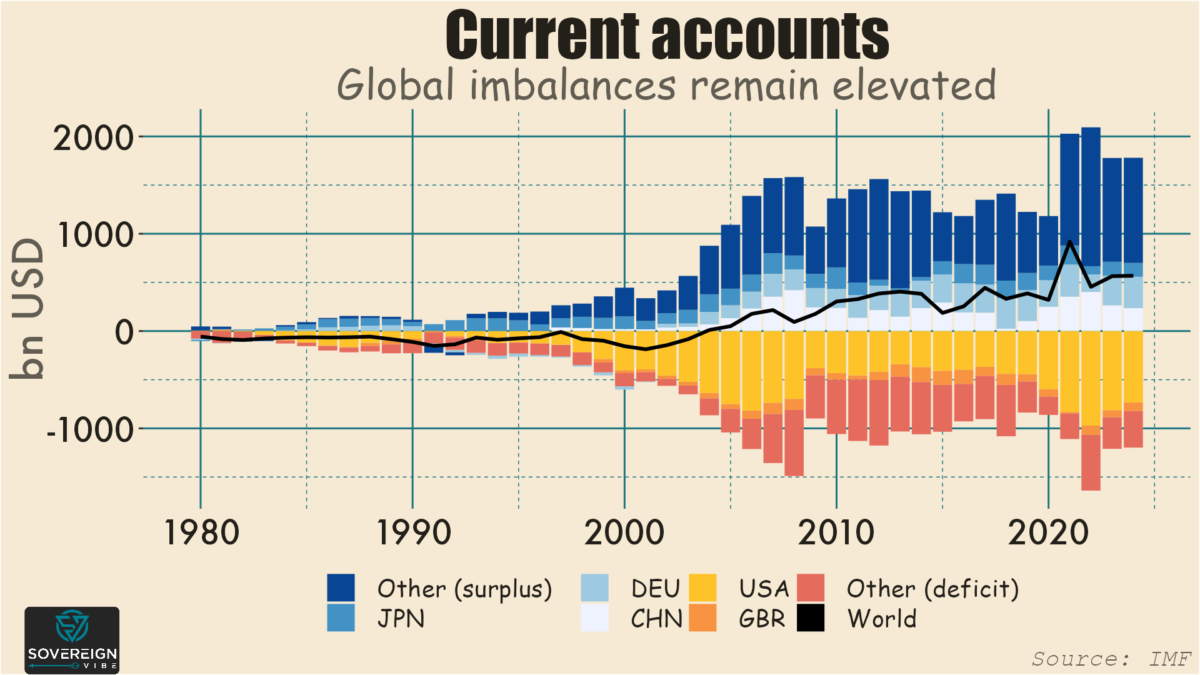

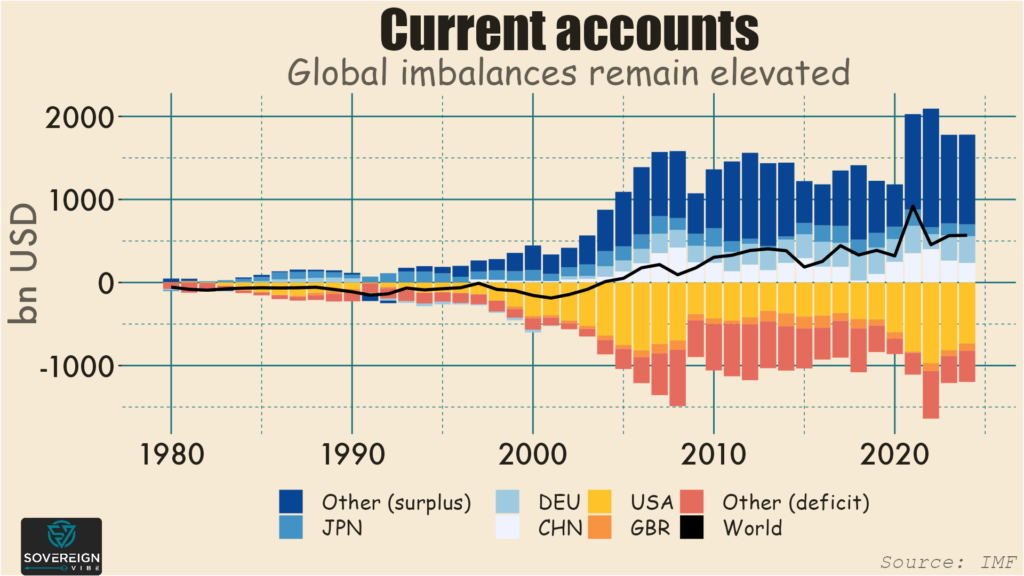

Essentially, countries that run current account surpluses – (remember that the current account is the trade balance plus other sources of foreign income) – are subsidizing manufacturing. China and Germany are prime examples.

In contrast, deficit countries are subsidizing consumption. The US and – to a much lesser extent – the UK have the largest average current account shortfalls in dollar terms.

One way to think about current accounts is that they are equal to savings minus investment, on a national level. Savings is of course the difference between income and consumption. So, when a country has a positive current account balance, it is saving more than it is investing. The reverse is true for CAB deficits:

Current Account Balance = Savings - Investment

It follows that for a current account to rise, savings increases and/or investment decreases. For a current account to decline, savings decreases and/or investment increases.

Capital account

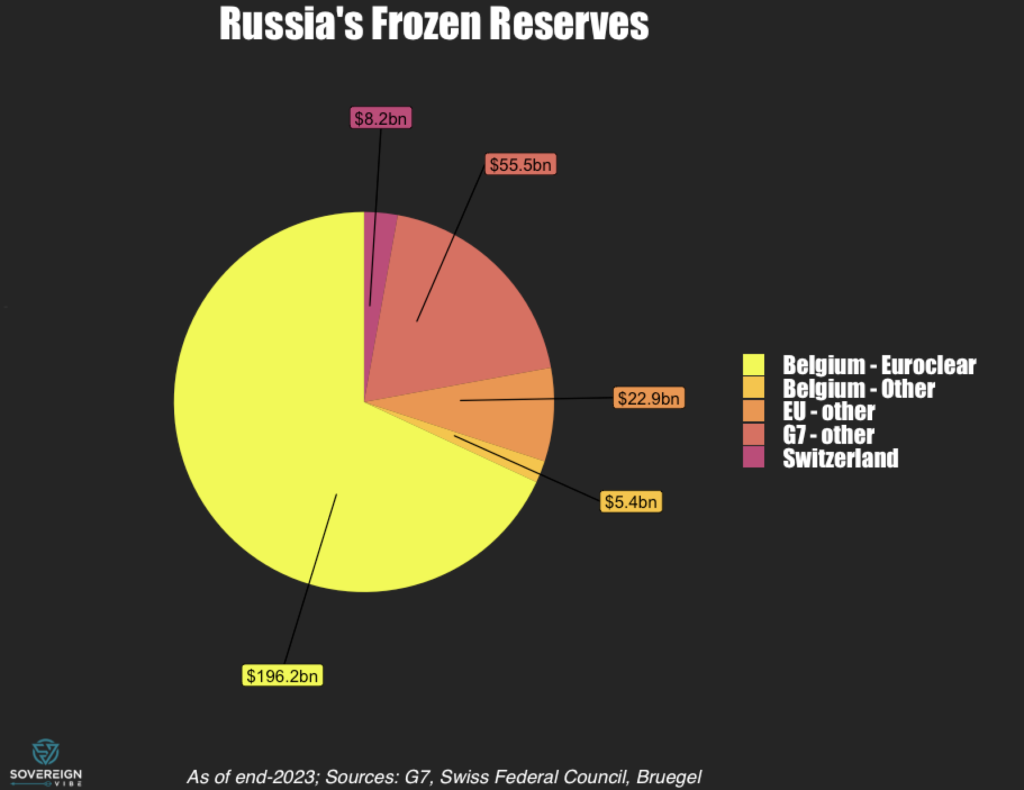

Another important piece of the puzzle is the capital account, which is open in the US and other G7 countries, but not in China. Investors understandably prefer to send their capital to countries with strong property rights, institutions, and rule of law. These robust investor protections is one of the reasons why the US and the UK and, to a lesser extent, Canada and Australia have such large deficits.

In other words, in countries with open capital accounts, when net international capital inflows are positive, the balance of payments means that the current account has to be negative (barring some potential temporary effects via international reserves dynamics).

Transfers, both internal & external

Surplus countries such as China, Germany, and Japan subsidize manufacturing at the expense of domestic consumers. Low interest rates and low wages, in China and Germany’s cases at least, result in net transfers from savers (i.e. households and workers) to manufacturing firms. Along with their manufactured goods, they are also “exporting” weak domestic consumer demand to other countries.

To resolve this external imbalance, deficit countries like the US and UK have to either decrease savings and/or increase investment. But, with companies either holding large cash balances or using them to buy back stock, there seem to be few signs of increasing investment. This means that savings must be negative. This can occur via increased unemployment, but, to avoid this, the government instead subsidizes consumption (at the expense of manufacturing) via increased household and/or government debt.

As such, exploding US government debt is partly a result of these external trade imbalances. This begs the question why the US accepts an undervalued yuan and large negative trade deficit with China, though the White House has certainly pushed back against this arrangement at various points.

Narrow interests

As is often the case, the status quo is a result that serves a specific set of narrow interests. With the US running such a large current account deficit, other countries acquire US financial assets denominated in dollars, meaning that the US exports its financial assets to the rest of the world. Doing so ensures the dollar’s status not only as a store of value but also as a medium of exchange internationally, which is what gives the US government power to levy financial sanctions and US banks power to dominate transactions.

Yet this situation is neither sustainable for the US government and households, nor is it desirable for most Americans. Even disregarding the overuse of sanctions, the effects of USD prevalence are negative abroad as well. For instance, greenback dominance has generally resulted in a strong dollar, which is not beneficial for global trade.

Unsustainable status quo: here to stay?

In fact, the global trading system works terribly. Ideally, wealthy countries would run surpluses, and EMDEs would run deficits in order to funnel rich-world savings towards domestic investment. But EMDEs present a variety of risks to investors, who prefer to have higher allocations to safer countries, e.g. the Anglosphere.

It is not the yuan or some other currency that will dislodge the dollar. Rather, it would be some combination of push and pull factors outside and inside the US. China and other surplus countries could stop incentivizing manufacturing and instead increase consumption and, in some cases, investment. US policymakers could reduce fiscal and household debt accumulation while encouraging exports of goods and services.

In both the surplus and deficit cases, restoring that balance between consumption and manufacturing would have broad-based economic benefits. Unfortunately, the prospects for either of these outcomes seem remote because of the political priorities of Beijing’s surplus maximization and of Washington’s dollar weaponization, both of which are cornerstones of this deglobalizing era. Yet since these imbalances are so unsustainable, something’s gotta give, someday.