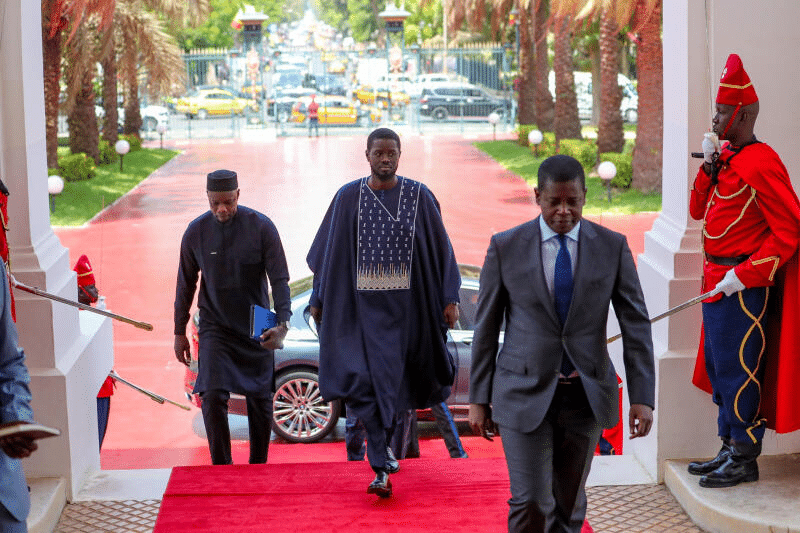

Today’s spotlight is on Senegal’s presidential election in March 2024 and the spectacular rise to power of political novice Bassirou “Diomaye” Faye, a 44-year old former tax inspector who went from prison to the presidency in scarcely 10 days. Digging beneath the surface of the electoral results reveals some oft-neglected ethnic undercurrents at play in Senegal and elsewhere in the Sahel that investors and observers should keep front of mind.

Why democratic stability is so rare in the Sahel

One of the things that struck me when living and working in Africa was the yawning gap between the international press coverage of electoral politics and the realities on the ground, which were both obvious and patiently explained to me by local friends.

I am of course referring to the ethnic dimensions of politics that are ever-present in so many African countries but that mainstream international media so often ignores.

In Africa, ethnicity doesn’t explain everything, but nothing can be explained without ethnicity.

Bernard Lugan

Democracy wins

Last month’s presidential elections in Senegal were first and foremost about the Senegalese people expressing their desire for change. As things currently stand, it is also a positive story of the country’s institutions resisting to pressure.

Indeed, Senegal has come back from the brink, after outgoing president Macky Sall sought to delay the elections indefinitely, and which – thankfully – the Constitutional Council overruled. The vote on 24 March saw opposition candidate Bassirou “Diomaye” Faye win a resounding victory that precluded the need for a second round runoff. A former tax inspector and political novice, Faye had been released from politically-motivated imprisonment only days before.

Yet the triumph was above all for Senegalese democracy, with government candidate Amadou Ba conceding the next day. The country thus remains a beacon of democratic stability with peaceful transitions of power since independence in an otherwise fragile region that has recently suffered a wave of coups d’état: Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Guinea. Beyond West Africa, Sudan, Chad, and Gabon have each had recent, idiosyncratic, coup-like political instability as well.

Mapping the ethnic X factor

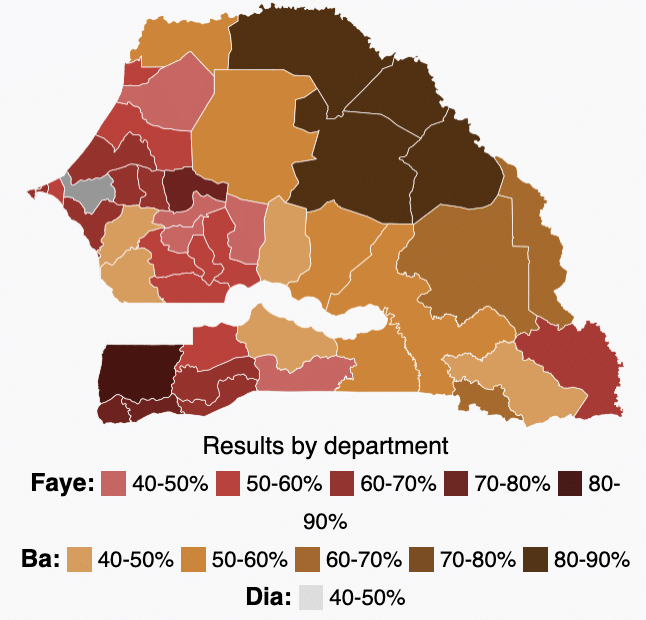

I don’t want to exaggerate the importance of ethnicity in this election. For all intents and purposes, the result is a clear repudiation of Sall’s government and his anointed would-be successor, Ba, and overrides potential ethnic considerations.

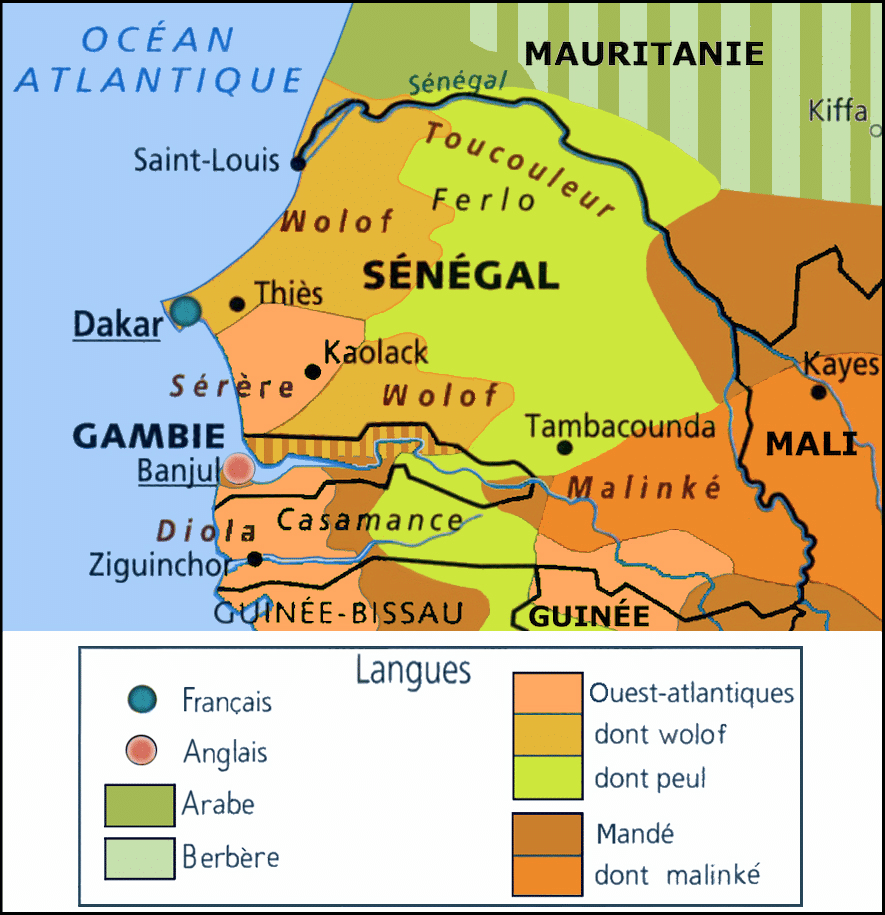

Nevertheless, comparing a map of the electoral results to an ethno-linguistic map of Senegal suggests that ethnicity is still important. Sall is Fula (in French: Peul) and has had his political stronghold in the northern parts of the country, where many Fula live. These voting patterns were borne out in March’s election, with Ba getting much of his support from Fula-populated areas.

In contrast, Faye was much more dominant in areas populated by the Wolof, the Mandé / Malinké in the southeast and south, and in the southwest. Faye was until recently the right-hand man of Ousmane Sonko, who was ultimately prevented from running in the election. Sonko hails from the southwestern city Ziguinchor, where Faye secured a strong turnout, and has been chosen as prime minister.

The Sahelian ethno-democratic-demographic doom loop

On a continent that crams some 3000 ethnic groups speaking around 2100 languages into a mere 54 countries, it is myopic to completely ignore the ethnic undercurrents at play, even in cases where it isn’t the primary driver. Yet analyzing the political salience of ethnicity in Africa is more than just a useful intellectual exercise.

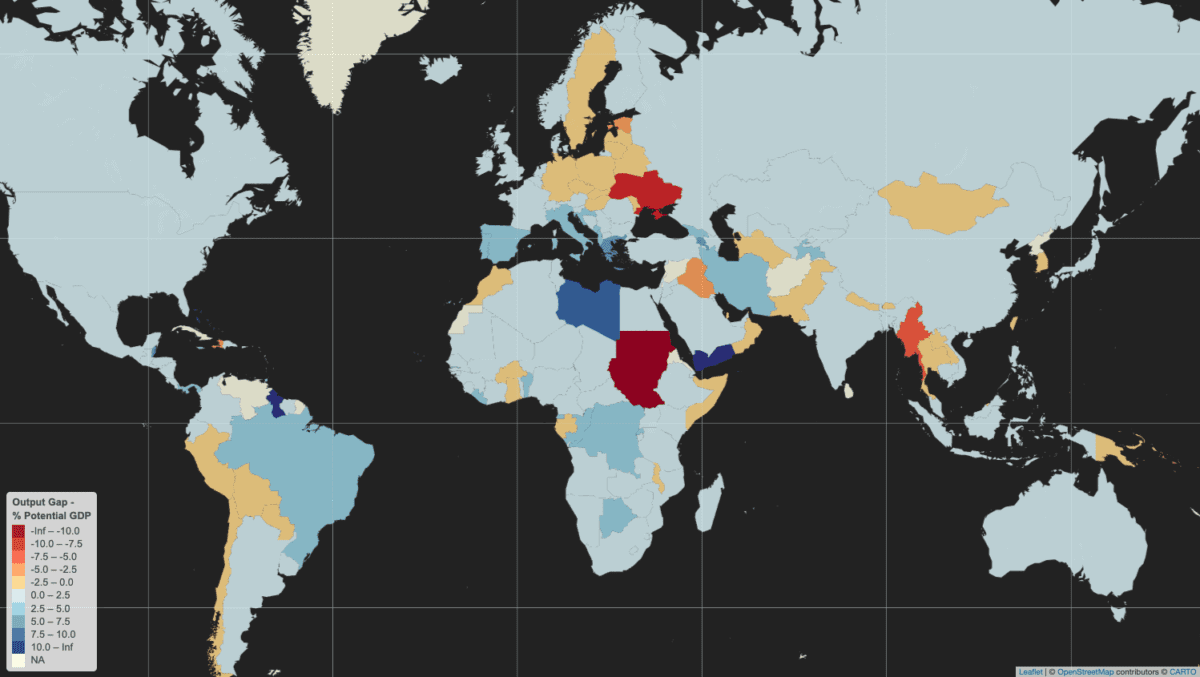

Think how, for example, as the largest nomadic pastoral community in the world, the Fula are present in Senegal and Guinea, and in Chad and Cameroon, and in every country in between. As climate change drives the Sahara’s expansion ever southward through the Sahel, we can expect land use-driven tensions to continue rising between the more martially-oriented nomadic pastoralists of the north and the more numerous sedentary agriculturalists to the south.

To that point on demographics, Western democratic ideals imposed on an African context partly explains many countries’ breakneck population growth. Individualism is at the center of the one-person one-vote approach to electoral democracy and works well in many parts of the world. But traditions of individual liberty were only introduced to African countries recently, where, historically, communitarian-led structures of societal organization tended to dominate.

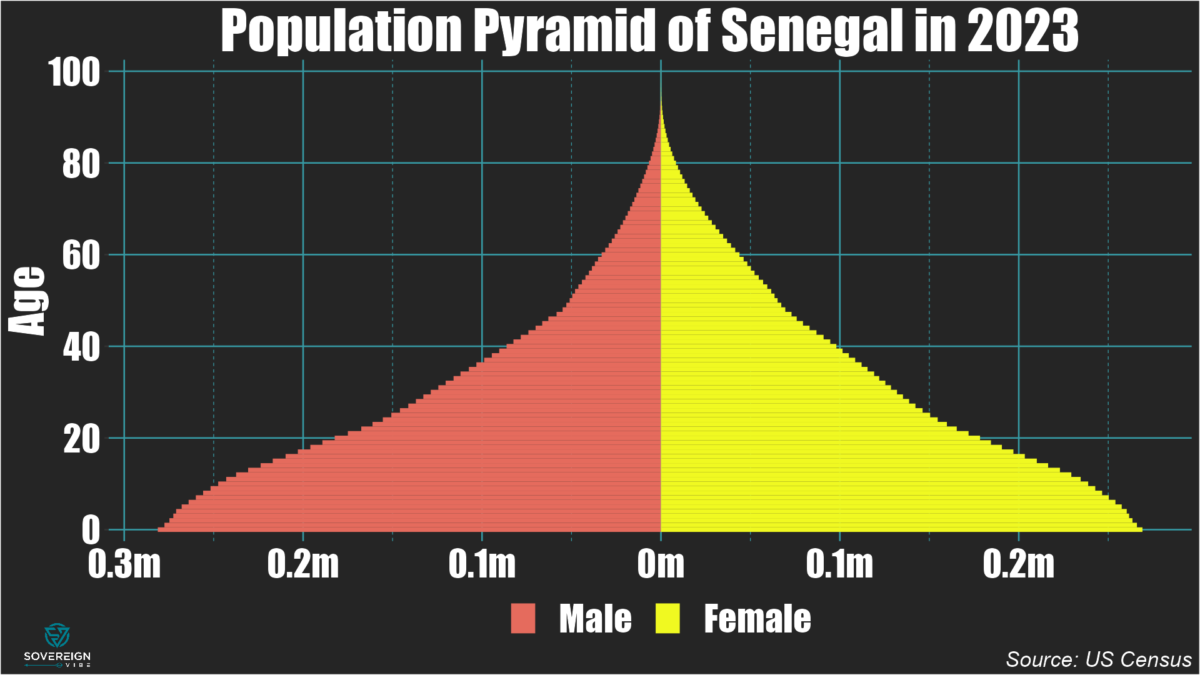

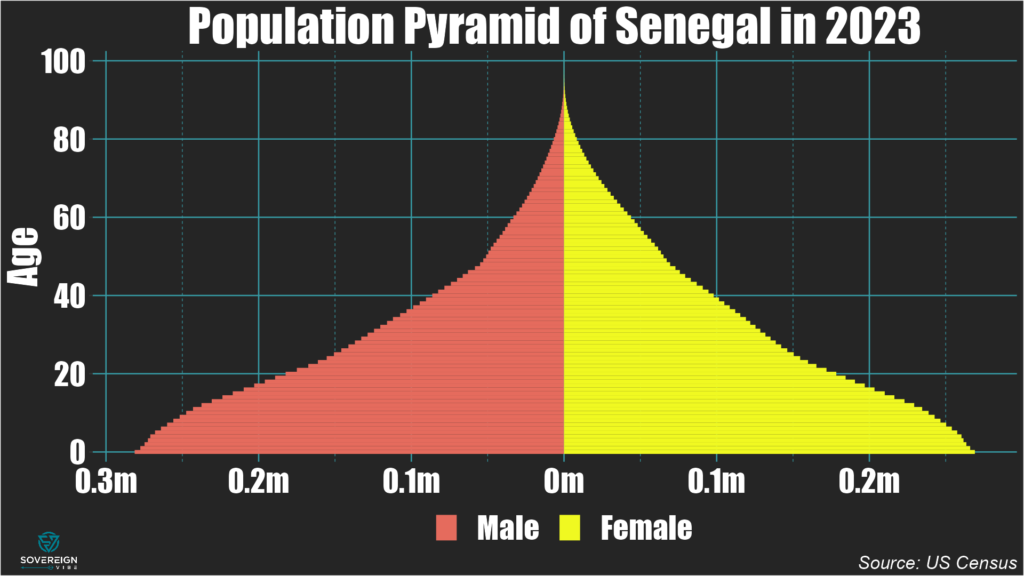

Thus Western-style democracy has incentivized each ethnic group to vie for political power by growing its population. This makes complete sense if one recognizes the communitarian focus that continues to drive politics in so many African countries to this day. Case in point, as of 2023 Senegalese women give birth to four children on average, and 75% of the country’s population is under 35 years old. Of course, the usual caveat applies: no single factor is fully responsible for a demographic outcome.

The bitter irony is that democracy has destabilized several of Senegal’s neighbors precisely because it has inverted the power relationship between the previously-dominant nomads and the sedentary farmers. Historically, these fierce warrior-pastoralists didn’t really require strength in numbers to subjugate their more pacific southern neighbors.

But in a context where democracy excludes the nomads from political power, it should not be at all surprising that these peoples would try to revolt or secede. This is precisely the driving force behind the ongoing conflicts and instability across the near-entirety of the Sahelian arc, rather than some inchoate jihadism. The several Tuareg / Azawad rebellions that have occurred since the 1960s serve as a prime example. Senegal alone has been spared. For now.

With all that in mind, can a victory of democracy in an African context be anything other than a pyrrhic one? I certainly hope so, and Senegal’s institutions give good reason to. Yet even as this result is rightly celebrated, the specter of roiling demographics and instability throughout so much of the region looms large over West Africa’s future.

What next for investors?

Investors have so far reacted to Faye’s victory with caution, as he is in many ways an unknown entity. It is still early days, so investors ought to remain circumspect while waiting to see the shape that his economic policies end up taking.

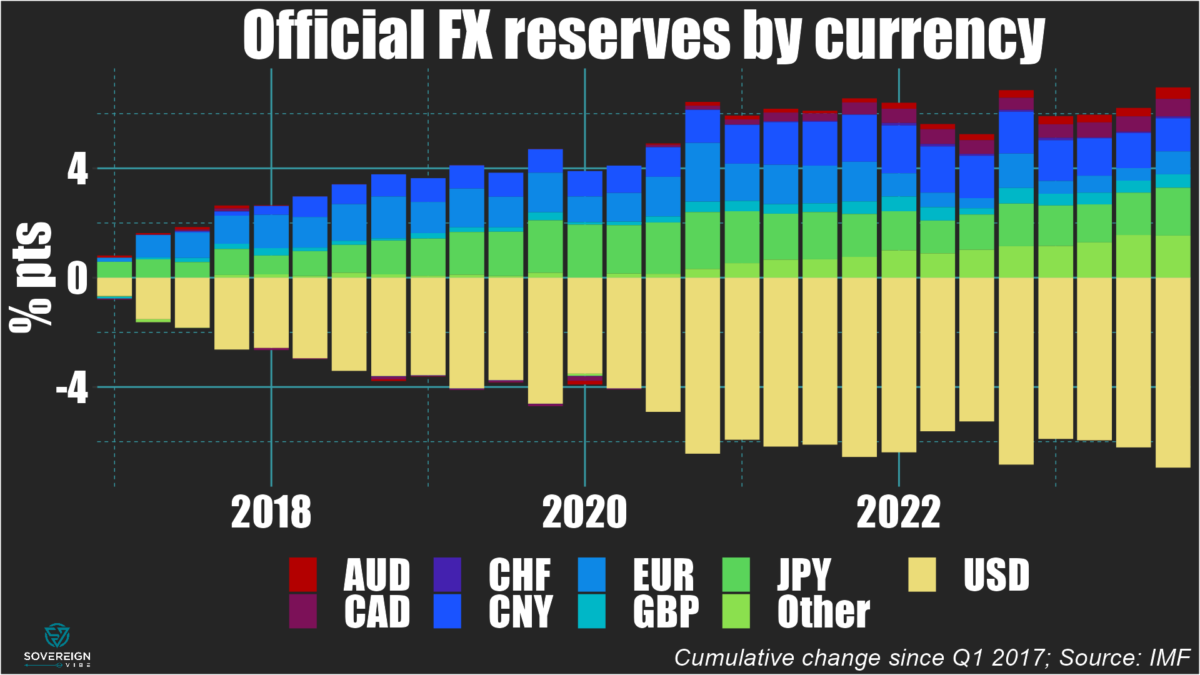

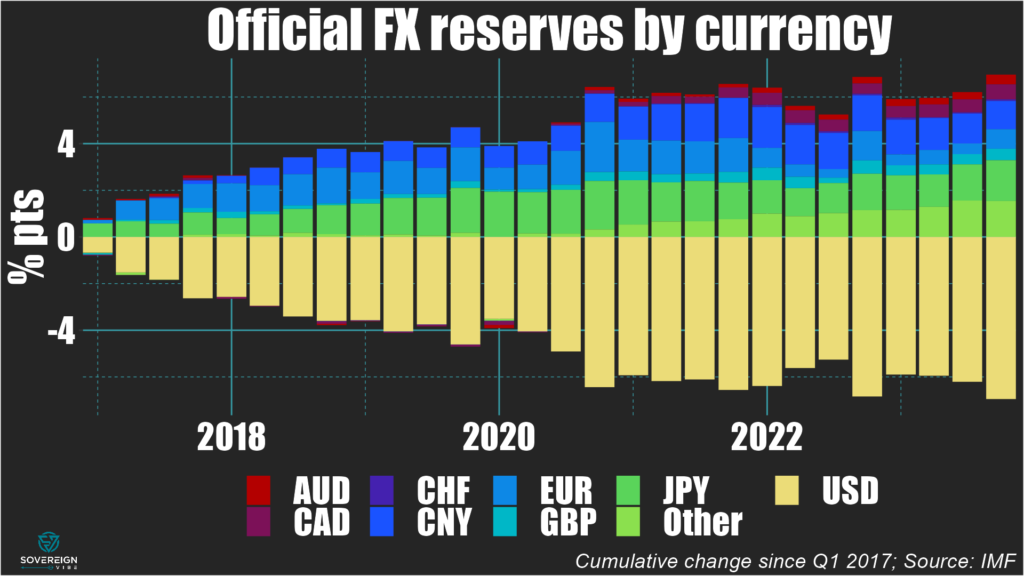

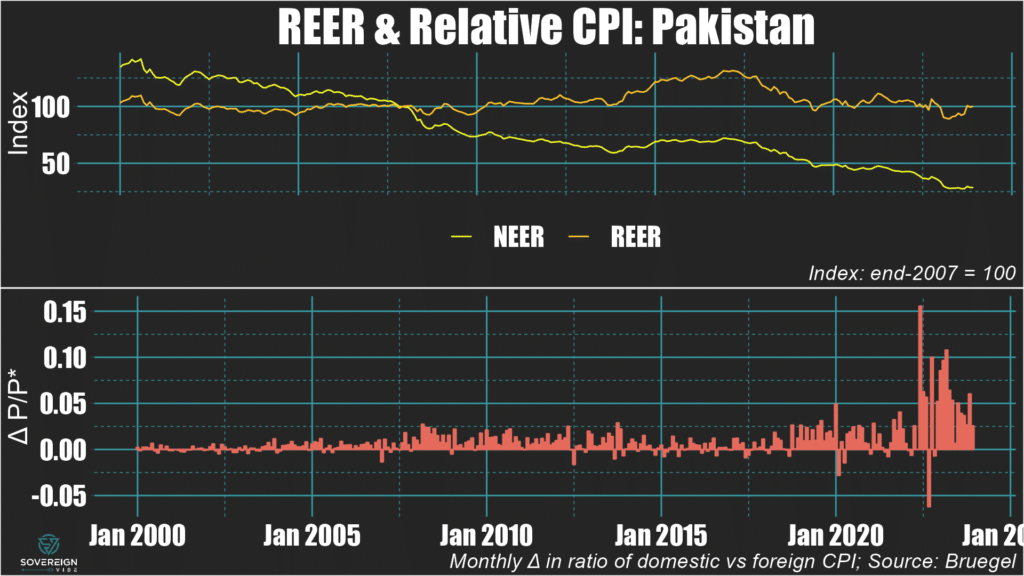

For now, what we know from Faye’s inauguration is that the economic agenda will focus on reducing cost-of-living pressures and on tackling corruption, while also having to address the high unemployment rate in this youthful country. On the external front, Faye and Sonko have espoused sovereignty and deep change, including reforms to or a complete transition away from the CFA currency.

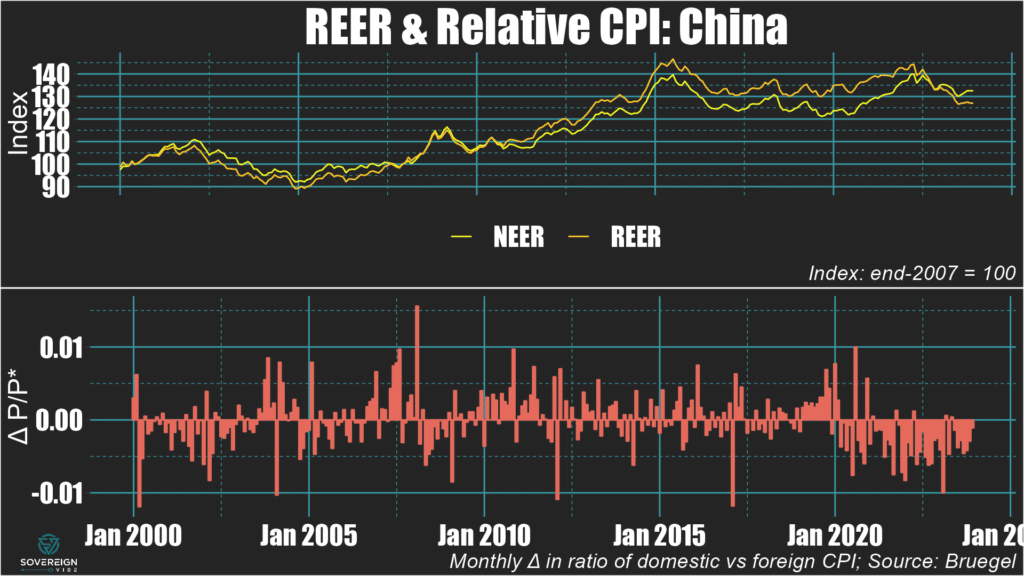

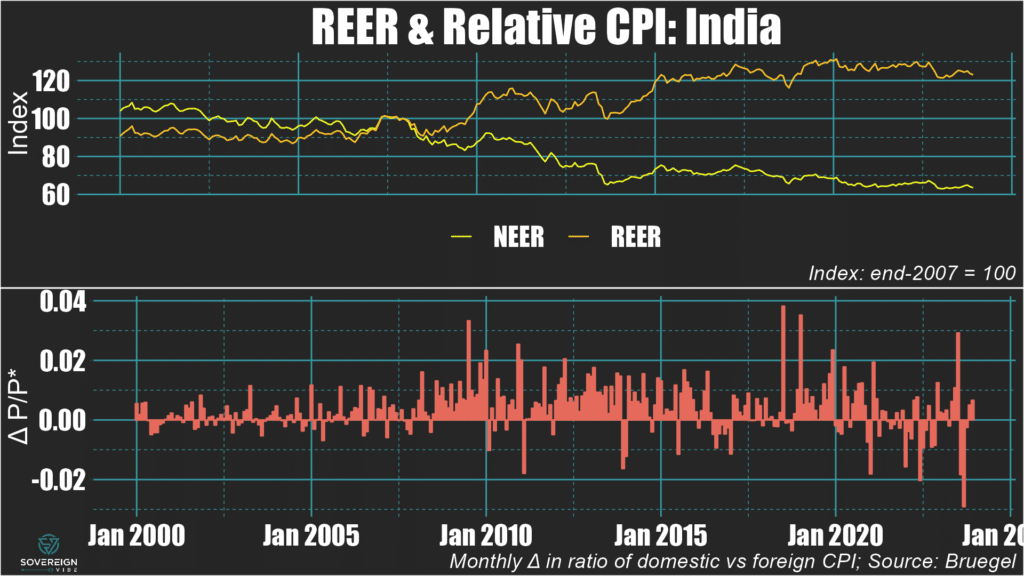

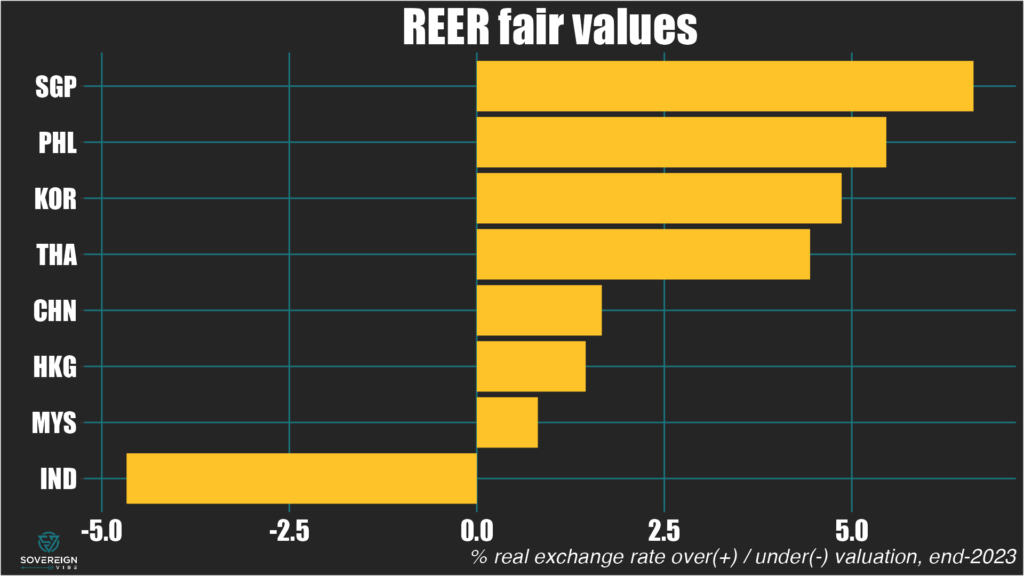

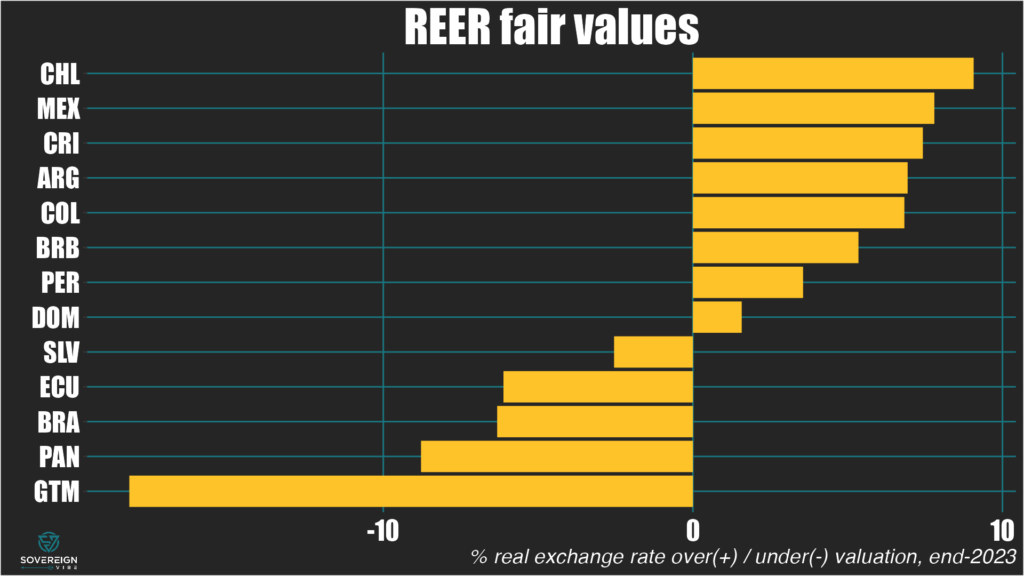

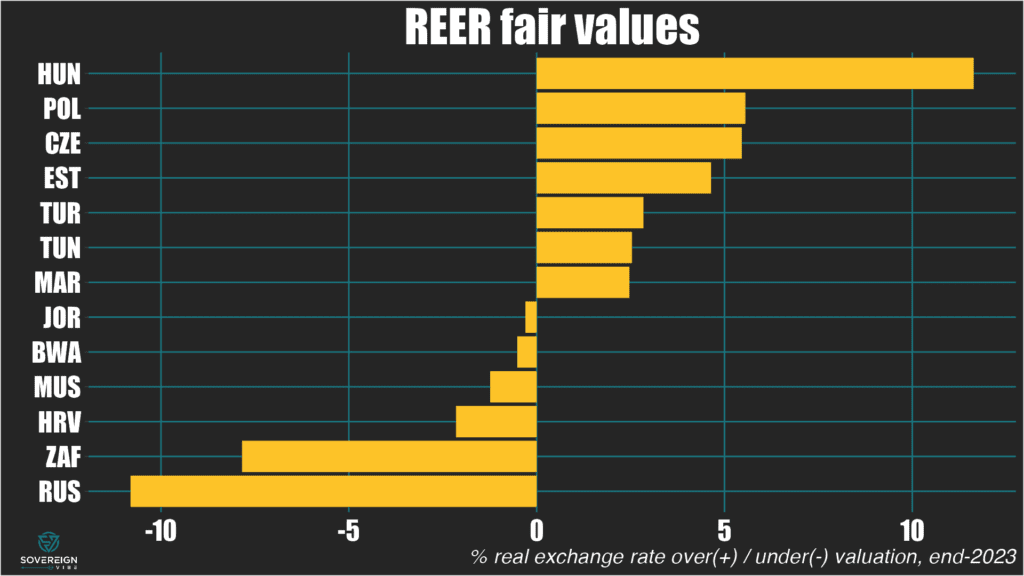

Abandoning the CFA could prove tricky, as the currency has been a source of stability throughout much of the region, aside from a sharp devaluation in 1994. On the other hand, Senegal likely has the policy credibility and institutional strength to pull it off. Moreover, the CFA is almost certainly highly overvalued, so the move to a more flexible currency could benefit export activity.

The French Connection

As for the relationship with France, Sall had kept close ties while also diversifying Senegal’s partners. It seems likely that Faye will keep Paris at arm’s length, without necessarily shutting the door entirely, if the cordial 30-minute conversation he had with Macron last week is anything to go by.

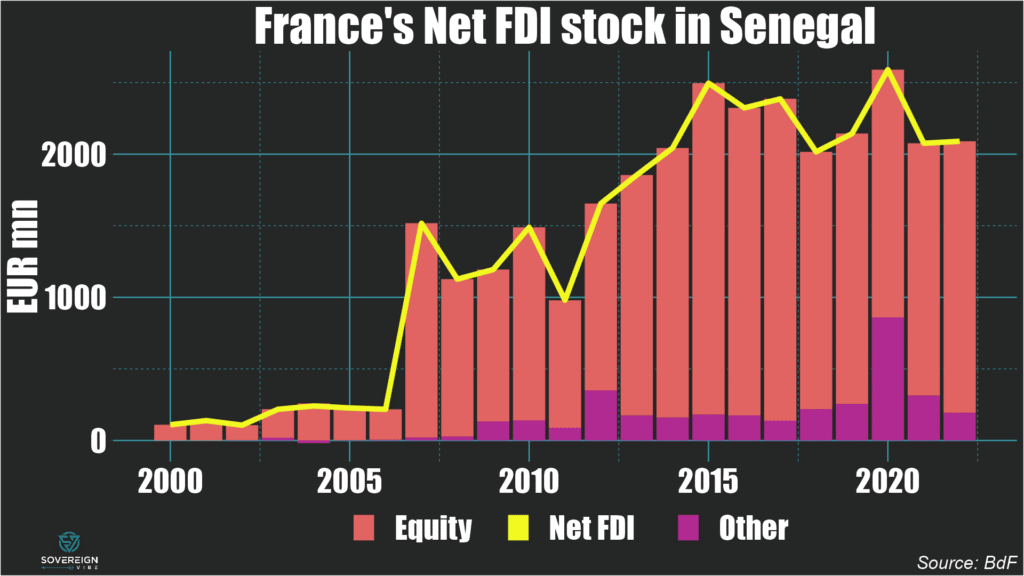

In the meantime, France’s net foreign direct investment stock in Senegal has remained above the €2bn mark in recent years, unlike declines in the French economic presence that have been registered elsewhere in francophone Africa. This level of FDI involvement in Senegal is close to 8% of GDP and represents nearly a fifth of FDI in the country, underscoring the ongoing presence that French economic interests are likely to have.