Famous last words, but this time could be different.

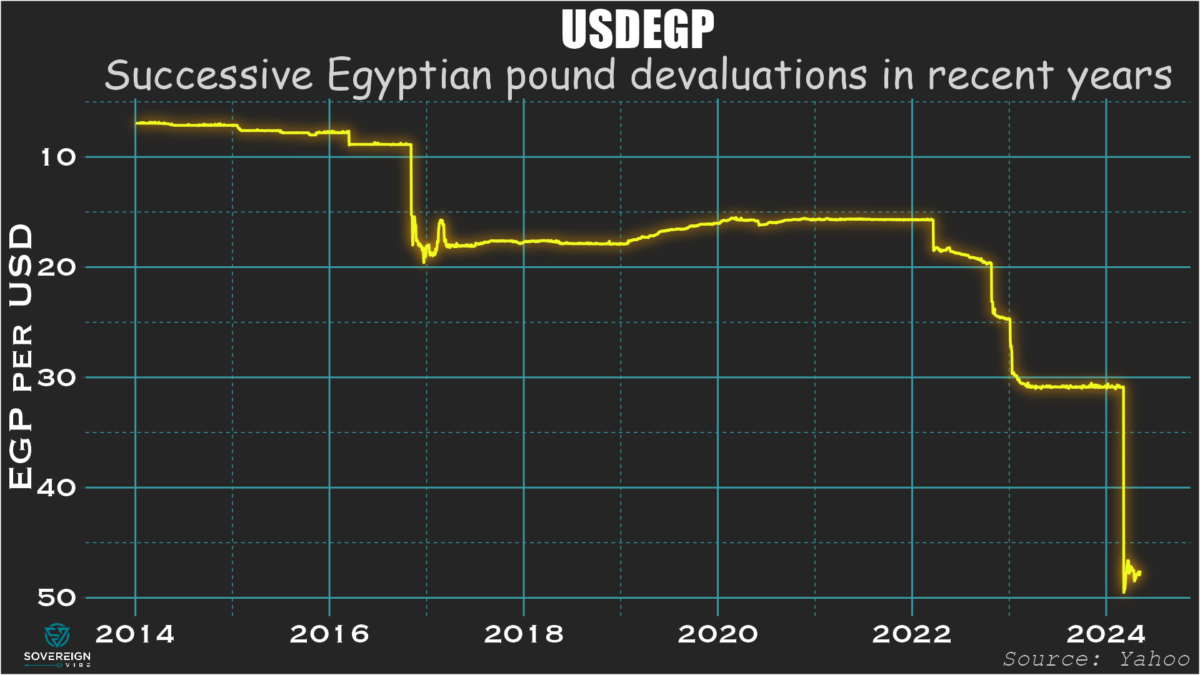

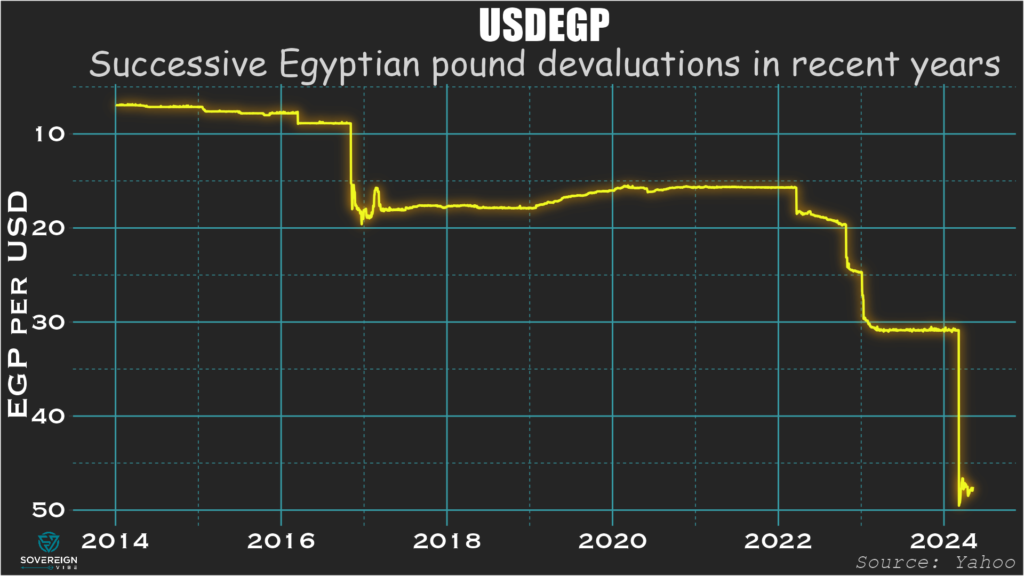

Big things are happening with Egypt’s economic policy management, and investors are taking notice. Though as with any other emerging market, the question that shouldn’t be asked is so often the same: is this time different? One of the most obvious symptoms of change is the major devaluation of the Egyptian pound, which slid from around 30 to the dollar to nearly 50 in early March.

Good news

Two major announcements for Egypt this year have been game changers in terms of easing FX payments pressures on the country. The first is a $5 billion increase in the IMF’s Extended Fund Facility to $8 billion, a clear vote of confidence by IMF staff over economic policymaking. The second is a blockbuster deal with Abu Dhabi-based ADQ to invest $35 billion in Ras El Hekma on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast, equivalent to about 7% of the GDP and planned for rapid disbursement.

This is all terrific news but will only matter in the long term if the government gets its economic policies right and restores macroeconomic balance sustainably. Clearly, the authorities are making strides towards a more flexible exchange rate regime. However, this is the sixth devaluation since the start of 2016, so observers should also temper their expectations regarding the authorities’ commitment.

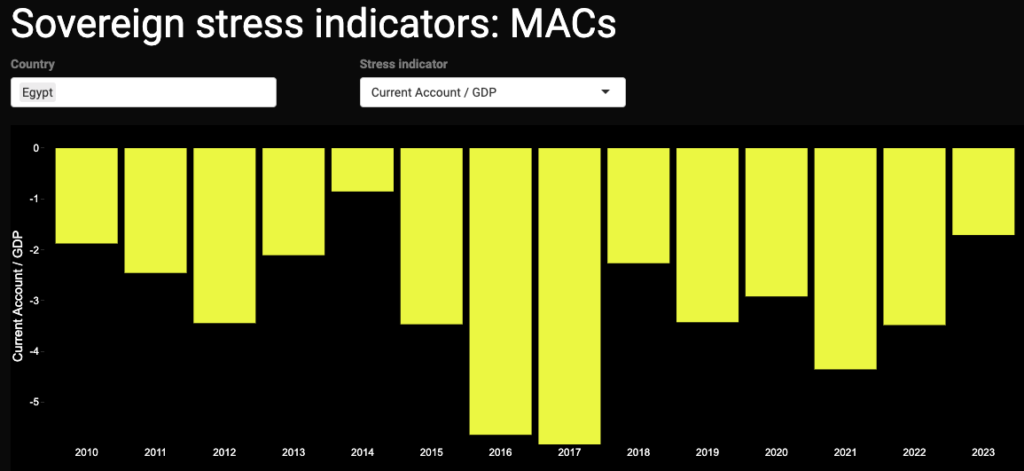

Yet the devaluations in 2022 are already having a positive impact. Using Sovereign Vibe’s dashboard of sovereign stress indicators, the current account balance (CAB) deficit has been narrowing:

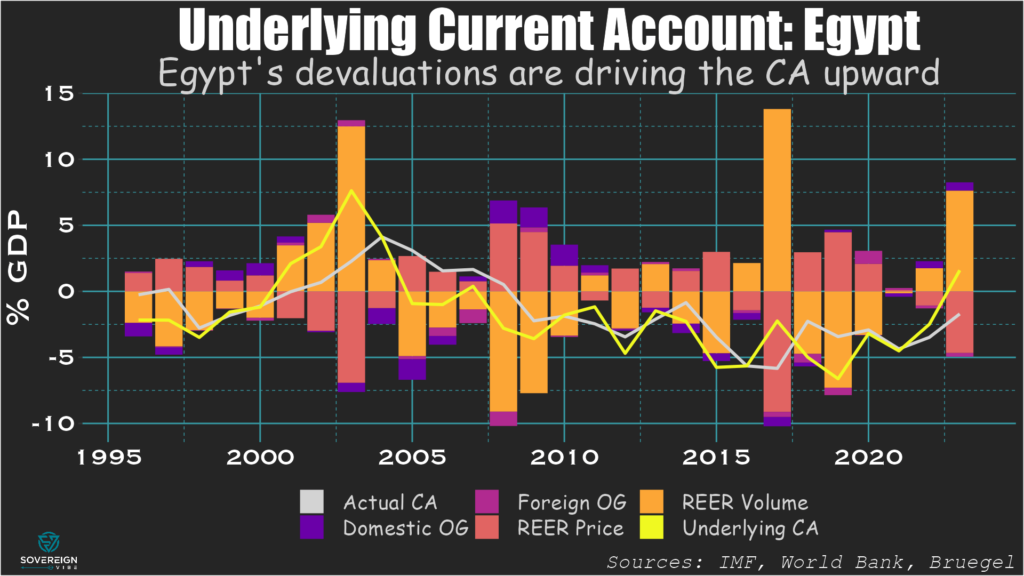

Diving in to more detail on how the 2022 devaluations have been helping Egypt bring its CAB back towards positive territory, taking a look at the underlying CAB is helpful. A crucial component of Sovereign Vibe’s broader fair value currency model, the underlying CAB is the CAB adjusted for the lagged effects of:

- real exchange rates changes,

- the domestic output gap, and

- the trade-weighted foreign output gap.

Egypt’s 2022 real devaluations had a small impact in 2022 and a large one in 2023 on trade volumes and trade prices. These always respond in the opposite way to REER changes. As seen here, a decrease in the REER (i.e. a devaluation) causes a positive volume effect on the CAB (chiefly via higher net exports) and a negative price effect on the CAB (via higher import prices). Crucially, the relevant literature finds that the volume effect outweighs the price effect. This is all good news for Egypt.

Short-term pain, long-term gain

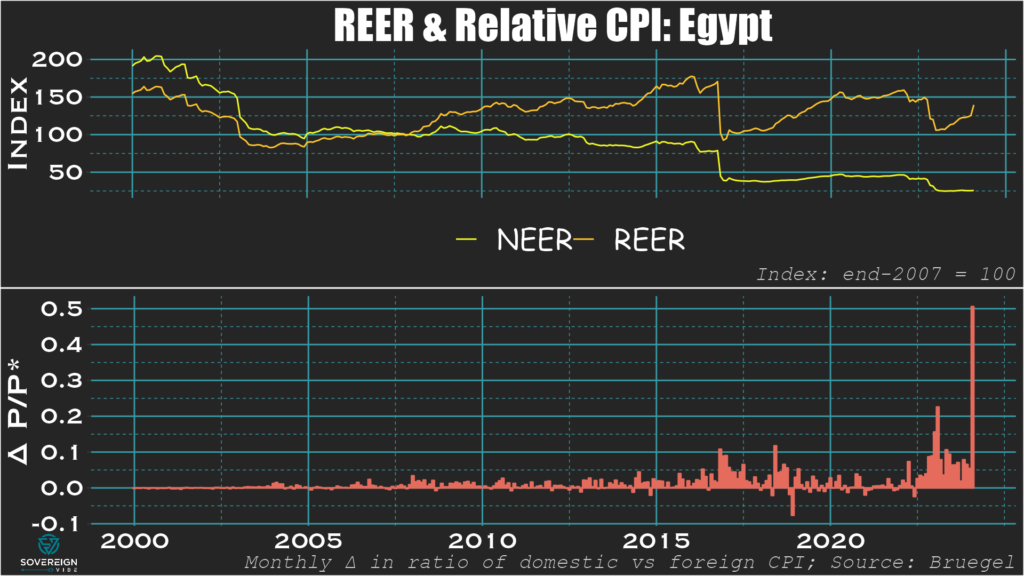

Here is some REER data through February 2024, right before Egypt’s massive devaluation this year. As you can see, the inflation differential with its trading partners was already skyrocketing:

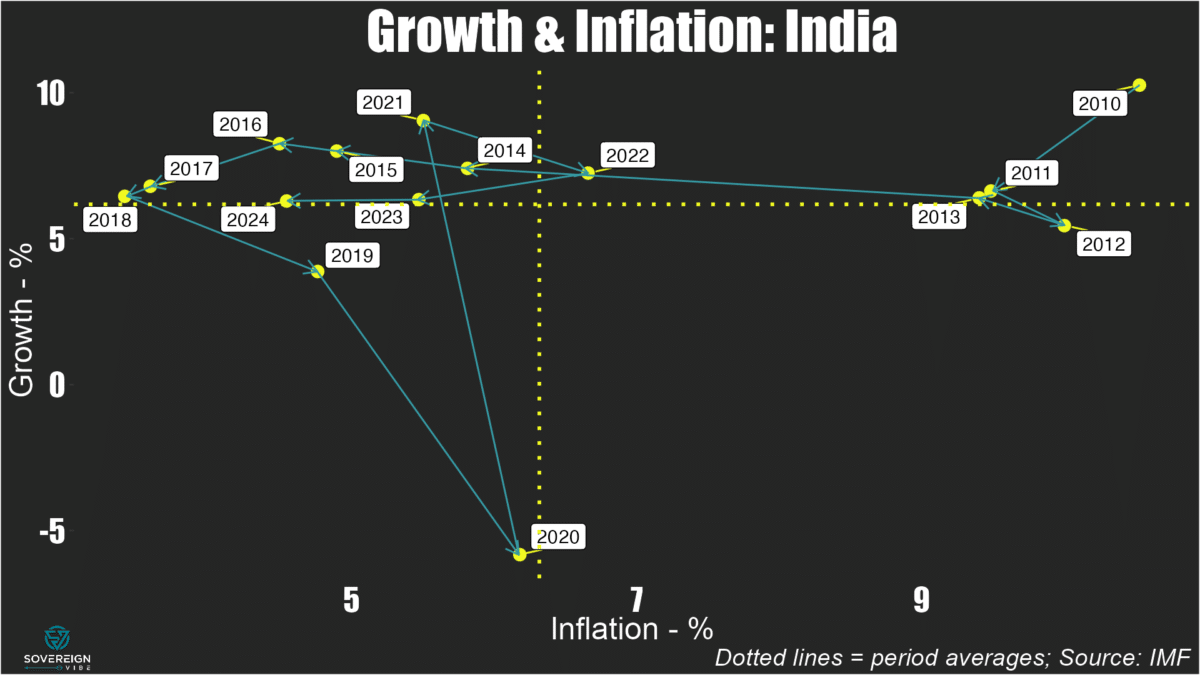

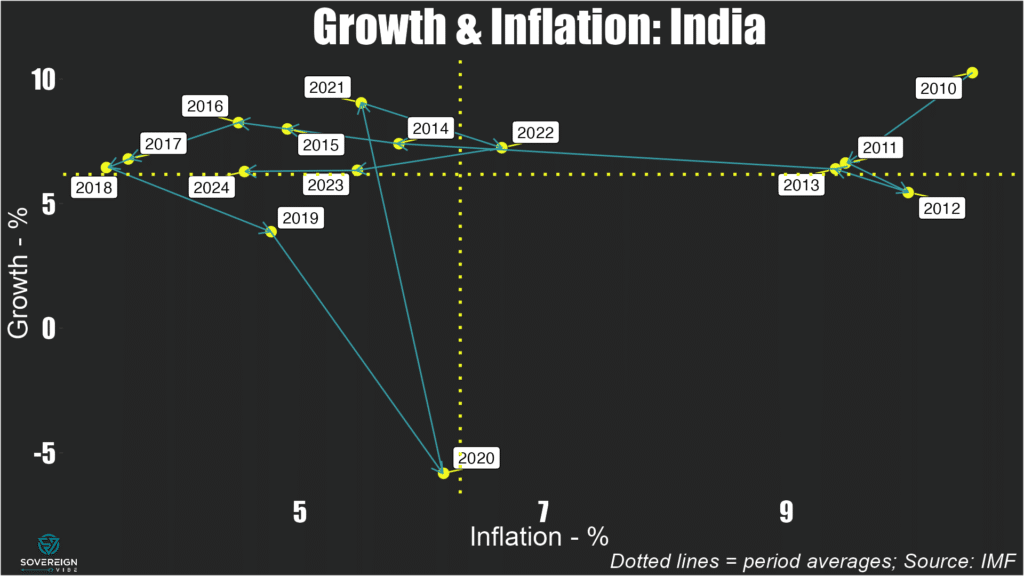

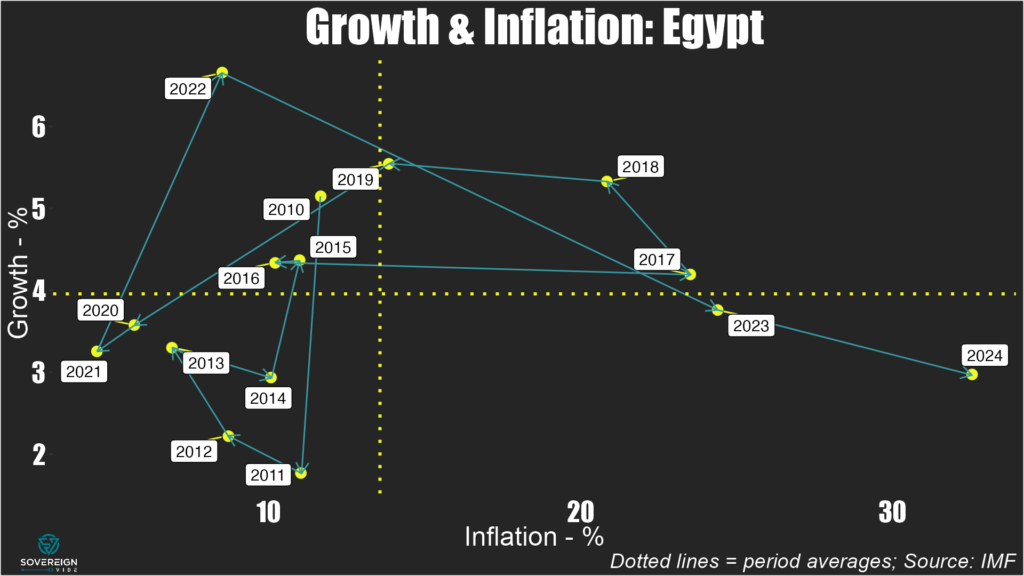

Inflation is indeed running rampant, with the IMF projecting it to exceed 30% over the course of 2024. This is of course extremely harmful to ordinary citizens who are seeing their purchasing power eroded. In response, the Central Bank of Egypt has taken the sensible step of increasing its policy rate significantly, by at least +800 basis points in Q1 alone. Unfortunately, growth has also been slowing since a post-pandemic rebound in 2022.

Public sector profligacy, private sector exclusion

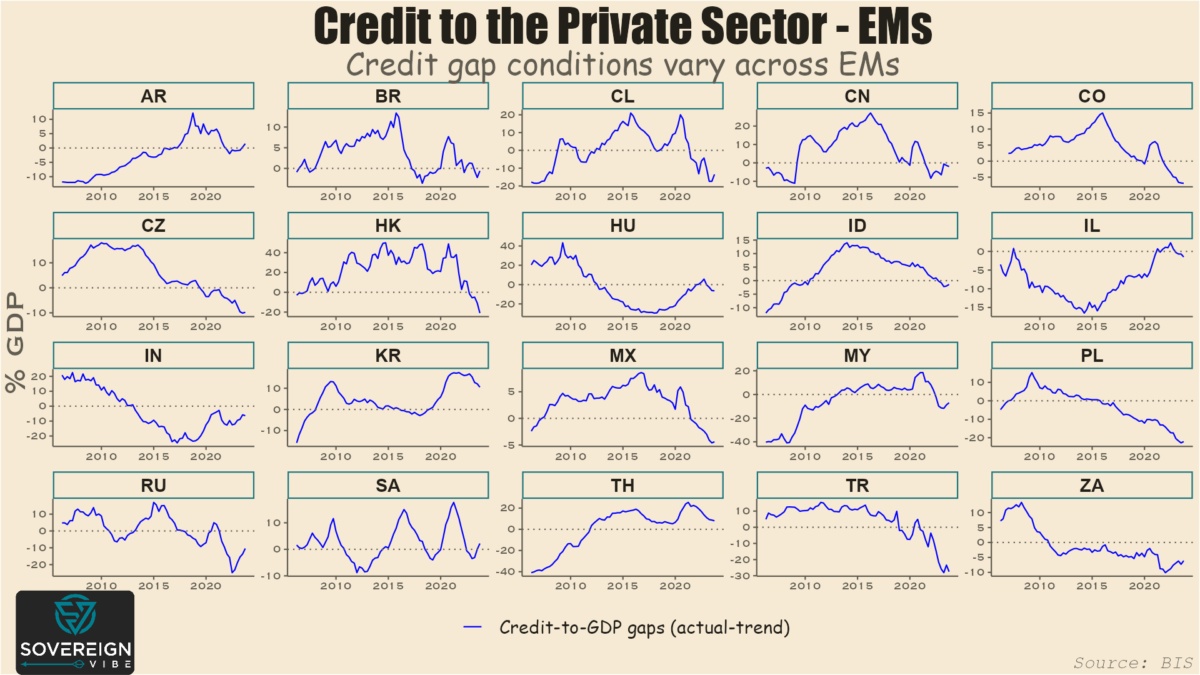

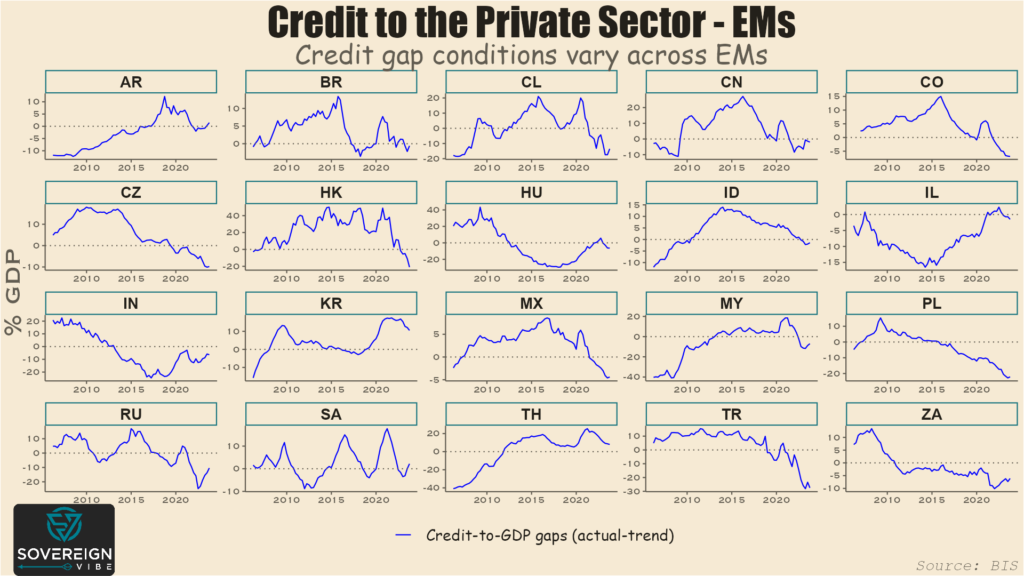

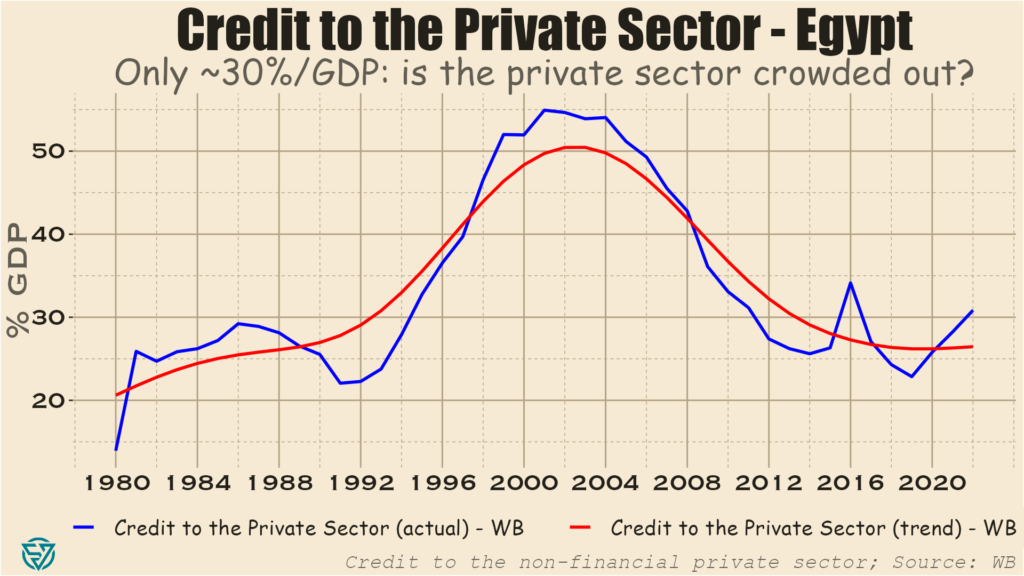

At only 30% of GDP, Egypt’s credit to the non-financial private sector (i.e. households and non-financial corporates) is significantly lower than in most other EMs. As such, it’s necessary to direct more credit towards the private sector, and this corresponds to the structural reforms the government is undertaking with IMF support. One change under way relates to eliminating preferential tax incentives for state-owned enterprises.

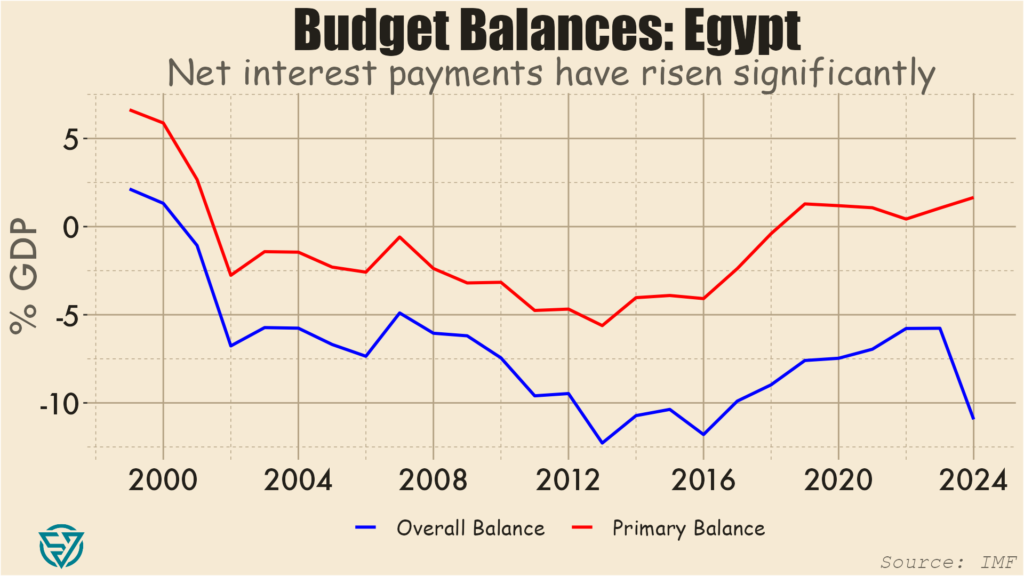

Egypt is a clear-cut case of public sector borrowing crowding out credit to the private sector. In other words, the government borrows so much that there isn’t much credit left over for firms and households. SOE tax breaks are only one symptom of this. The bigger picture is that the government has been running budget deficits in excess of 5% of GDP since 2008. All that net borrowing has caught up to the government, as net interest payments have grown markedly.

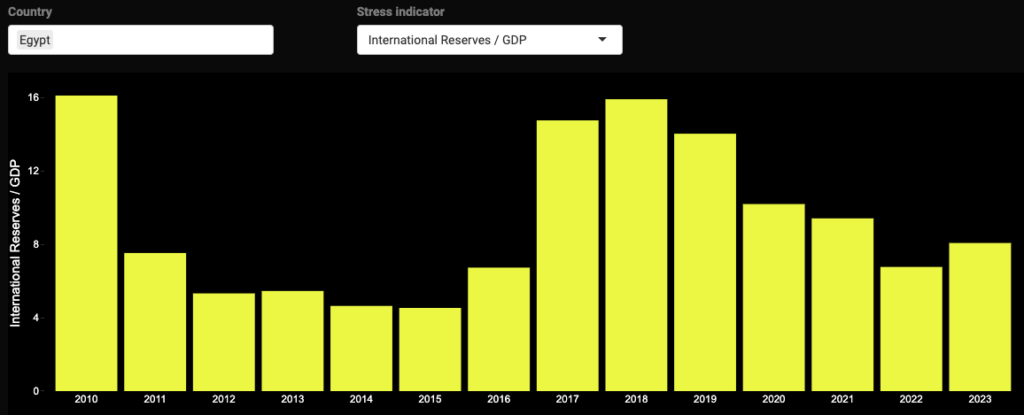

The primary budget balance, which excludes net interest payments on debt, has actually been positive since 2019. In 2024, the gap between the overall and primary budget balances is projected to be ~15% of GDP. This gap is equal to net interest, suggesting net payments of around $70 billion this year. For comparison, Egypt’s official international reserves stood at only ~8% of GDP in 2023, though these are no doubt increasing substantially in 2024 amid the IMF and ADQ disbursements.

Silver lining

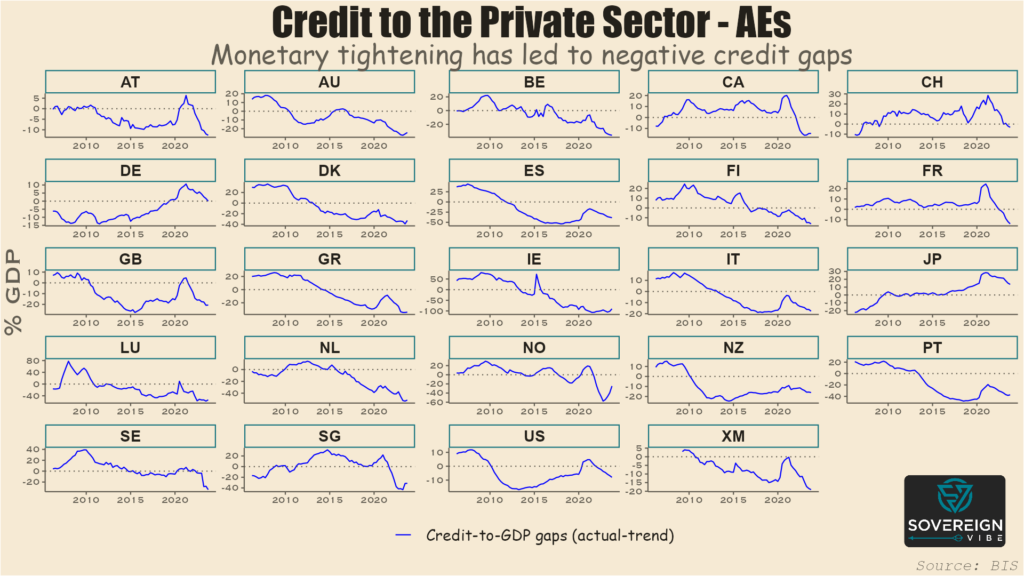

So the policy prescription is quite clear: re-direct resources and credit from the wasteful public sector to the private sector and unleash its productive potential. Increasing lending to the private sector, or any sector, is challenging amid monetary policy tightening, which Egypt is currently going through in its battle against inflation, but must be the medium- and long-term plan.

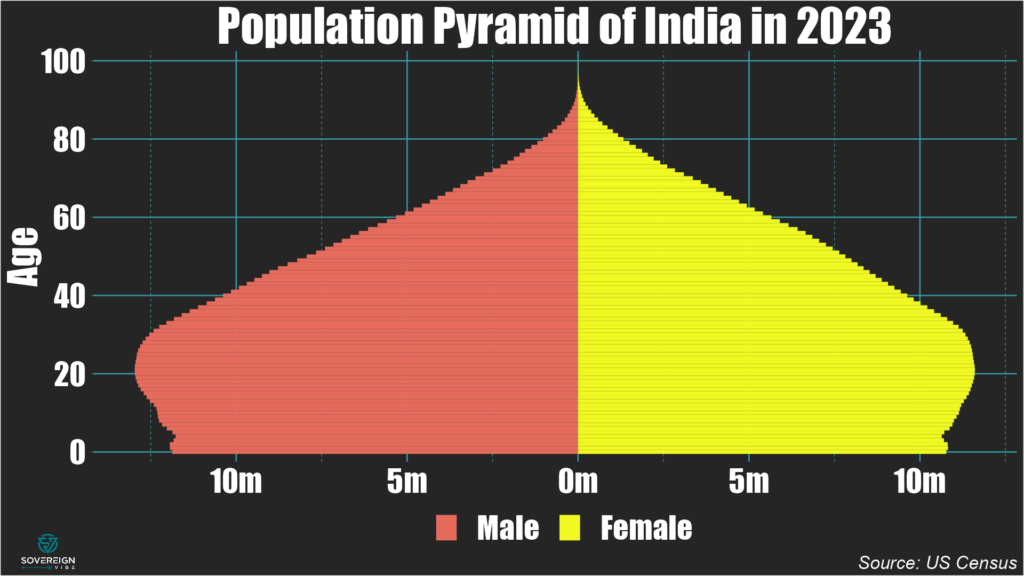

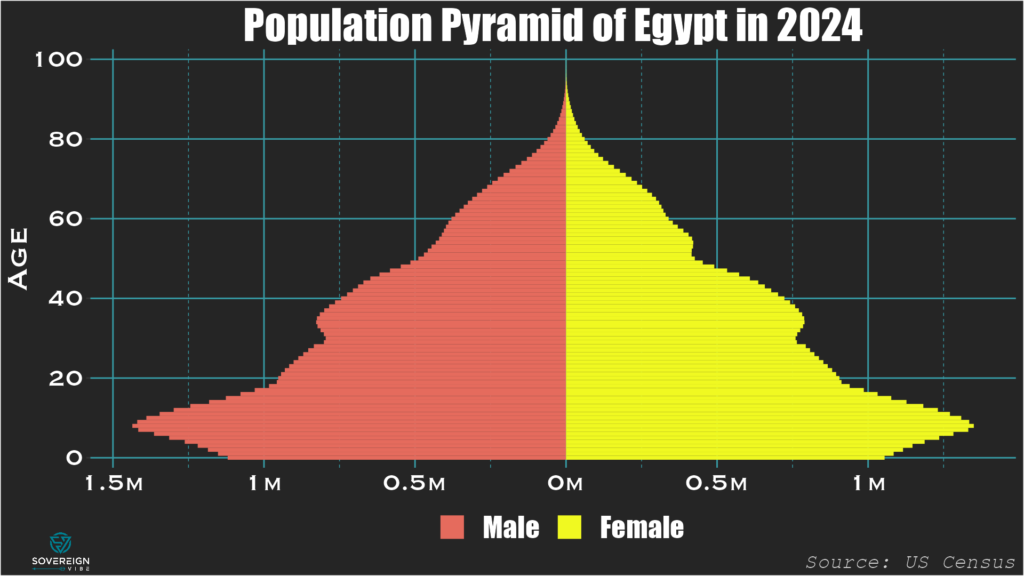

If the authorities can get it right, the Egyptian economy’s best days should be ahead of it, as the demographic trends are evolving favorably. The government has succeeded in bringing the birth rate down from 3.5 to 2.85 per woman in the past five years, which is converging towards the replacement rate of 2.1. In this country of 105 million, youth unemployment will likely remain a challenge in the short- and medium-terms, but these pressures should abate over the long-term ceteris paribus.

The 2024 devaluation, for all the short term pain via exchange rate inflation pass-through, should help unlock export-oriented opportunities for the economy and thus stoke growth, decrease unemployment, and put the government on an improved budgetary footing.