Double-whammy of higher U.S. yields and stronger dollar, with peak deglobalization still to come

Most people think my newsletter is only about sovereign debt.

This is a fair assumption: after all, “sovereign” is in the name.

But it’s also about deglobalization, geoeconomic fragmentation, slowbalization.

Or whatever other convoluted term you want to label the post-2016 Trump victory 1.0 and Brexit world as.

I write about these topics as well because they are so closely intertwined with what is happening in the emerging markets and sovereign debt space.

The daily symptoms of this world are often sanctions and tariffs, or any other number of phenomena that harden borders and disintegrate international relationships.

And it’s this reigning ambiance that also led me to call this newsletter “Sovereign Vibe.”

Countries are turning inward, putting themselves first, and promoting isolationist and protectionist policies in one form or another.

It’s sovereign first, friends next, enemies last, and multilateralism forgotten.

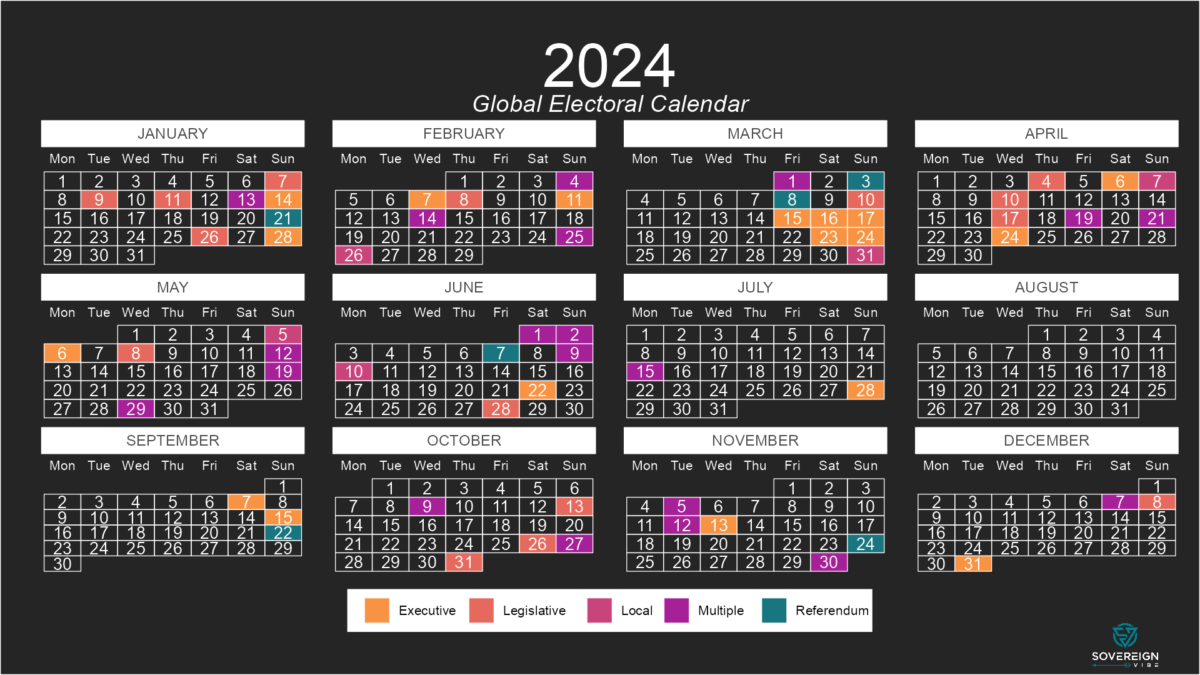

Never has that been more true than after Trump’s sweeping 2024 electoral triumph, carrying the U.S. popular vote and a strong mandate for “America First” policies.

Buckle up: we’re going to be in for a wild four years and beyond…

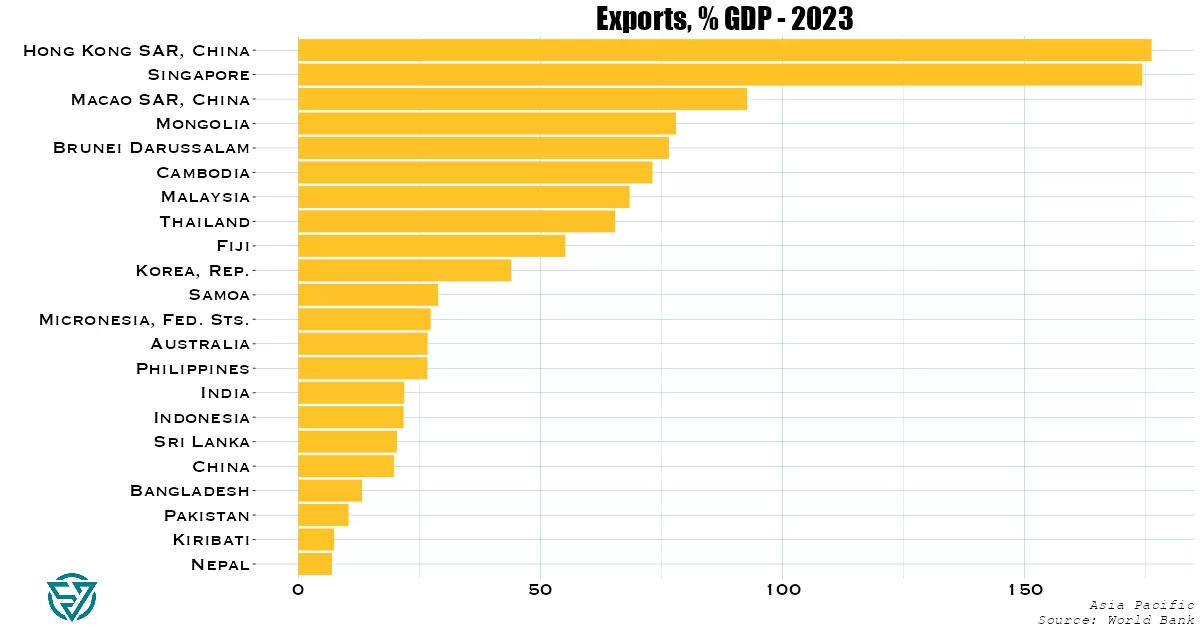

Exporters at risk

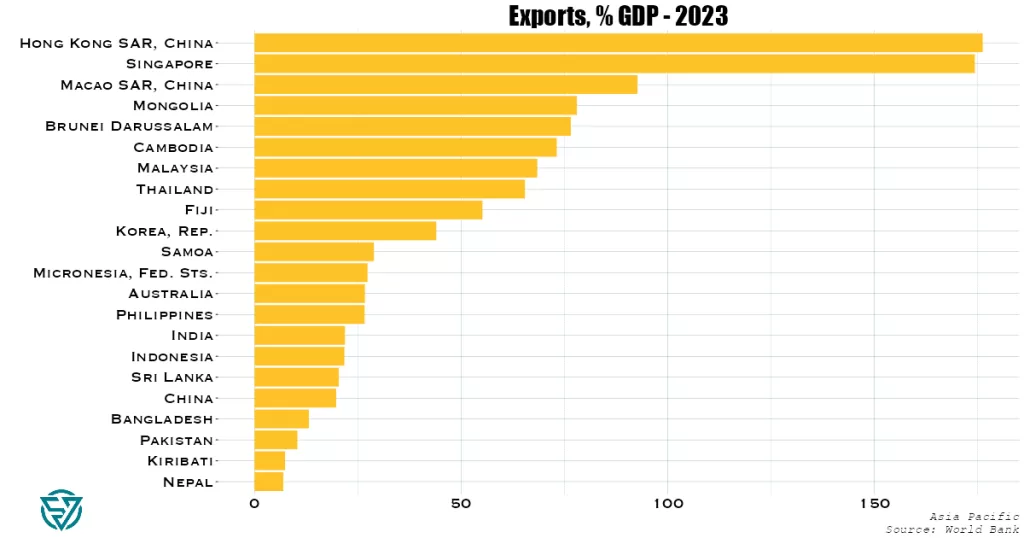

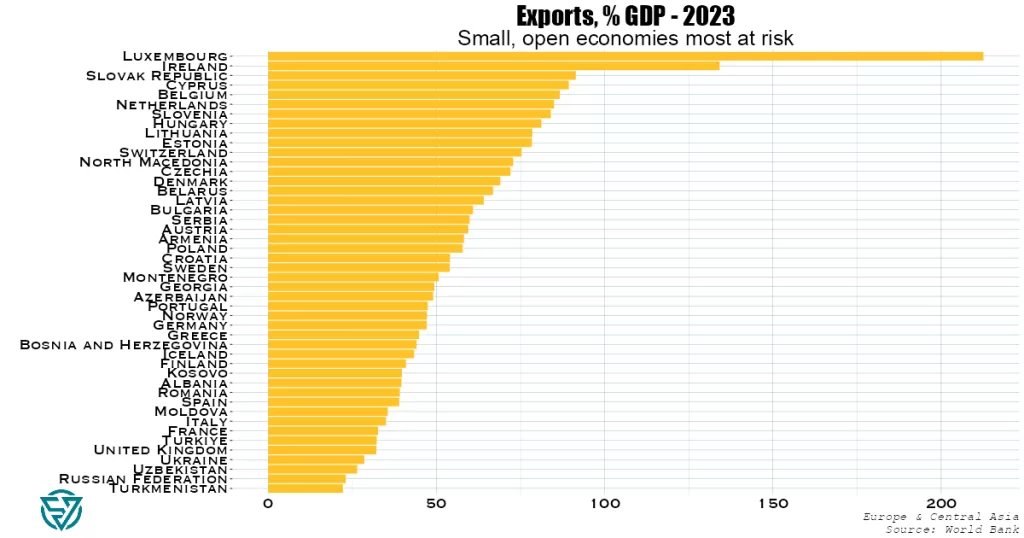

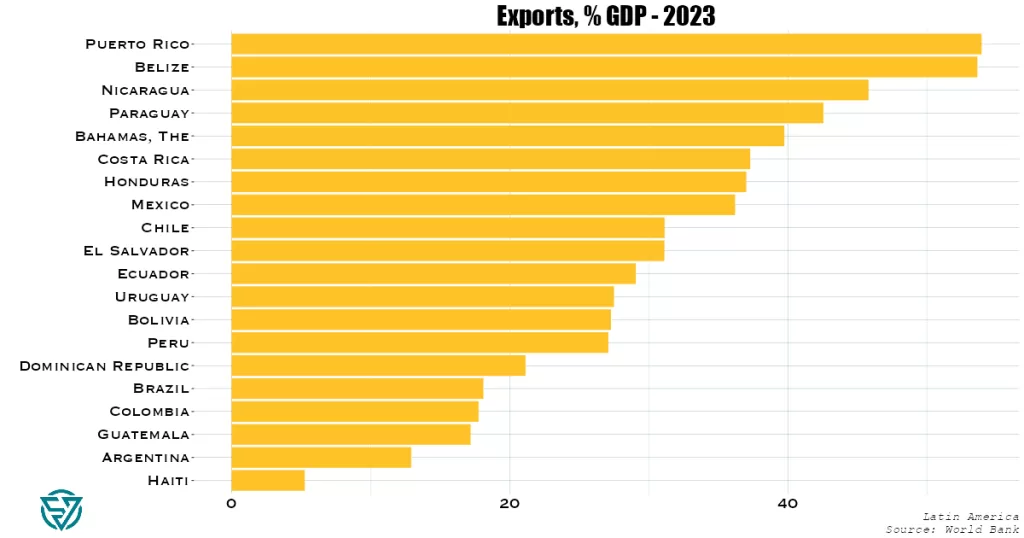

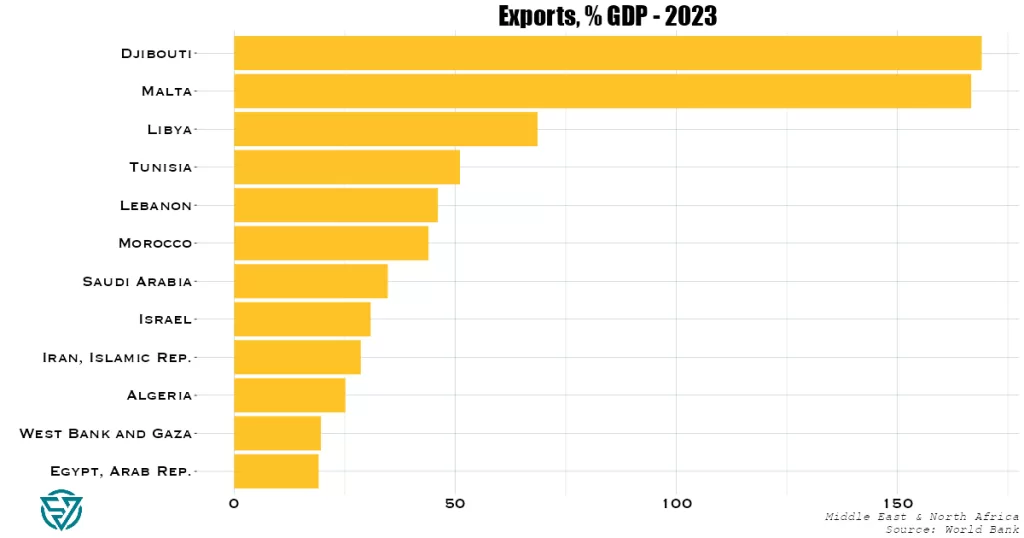

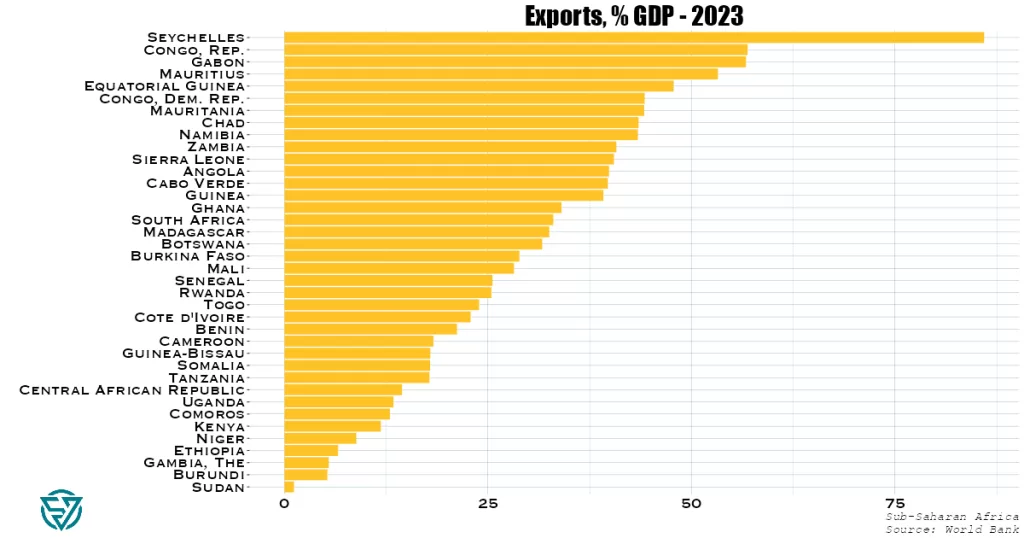

With Trump proposing 60% tariffs on imports from China and 10-20% on imports from the rest of the world, countries with a heavy reliance on exports are at risk.

This is especially true for countries with direct export exposure to the U.S., though interconnected global supply chains means that countries with high shares of exports to GDP may be particularly vulnerable.

While Trump’s trade policies may take aim mainly at manufactured goods, it is unclear the extent to which they will target services and raw materials.

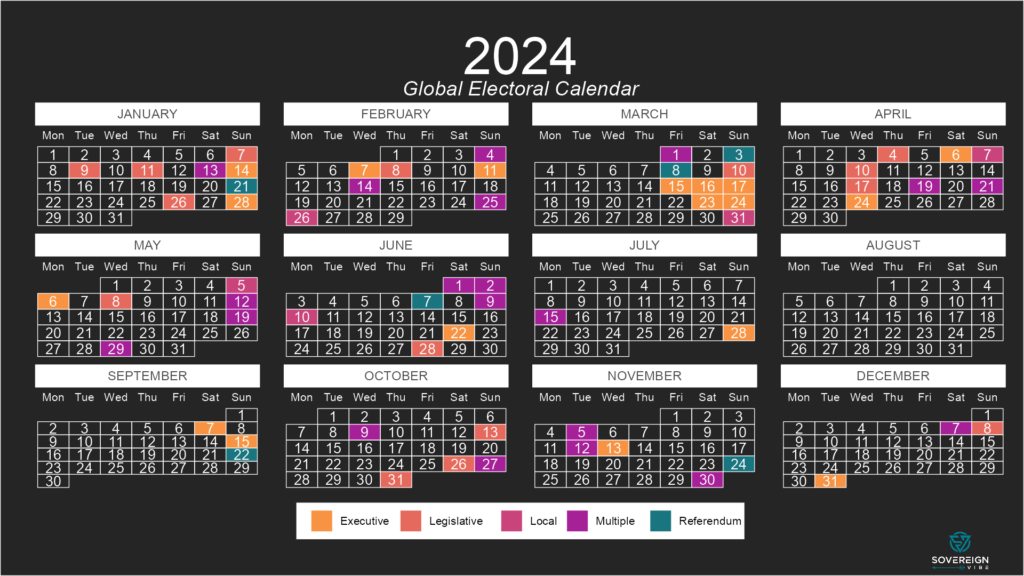

The charts below break down export exposure by region:

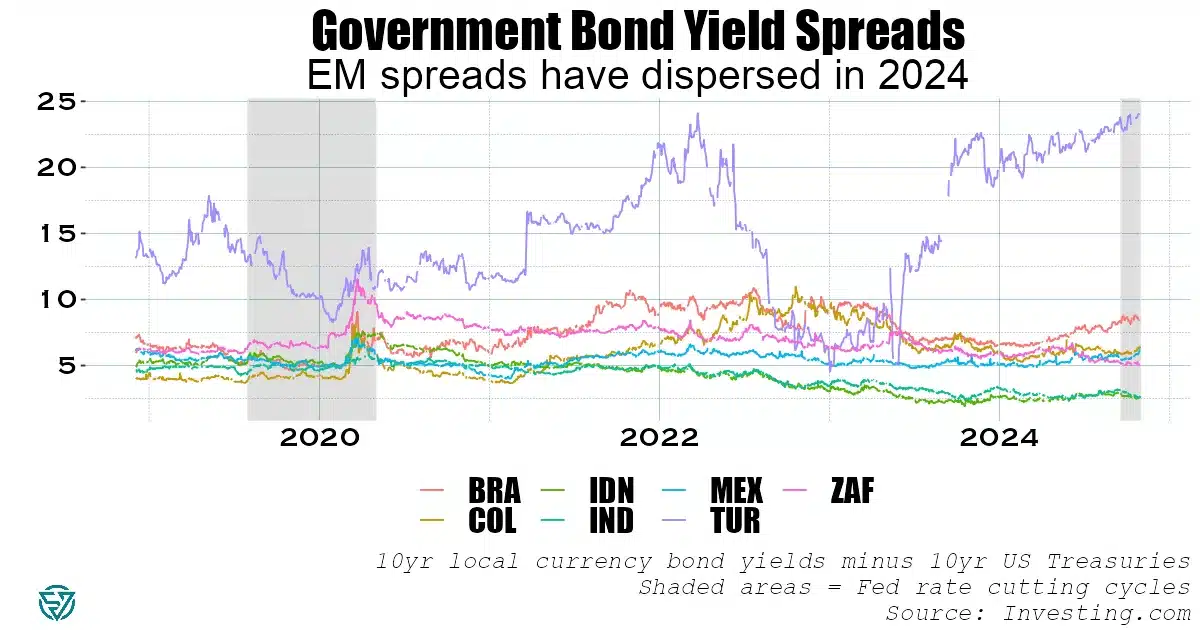

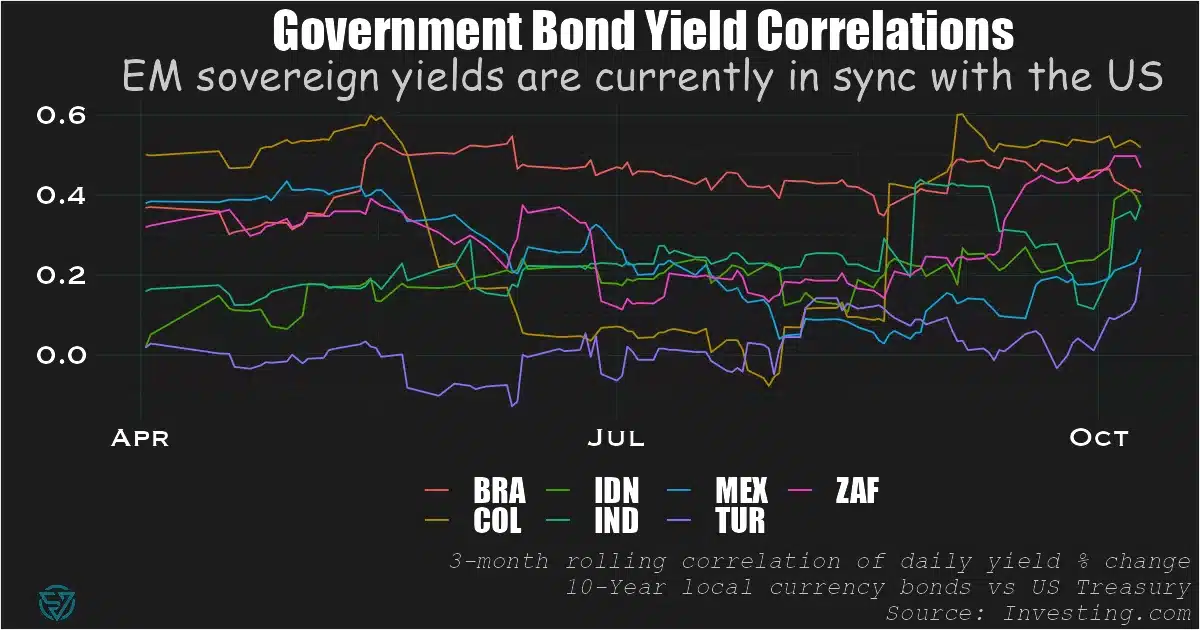

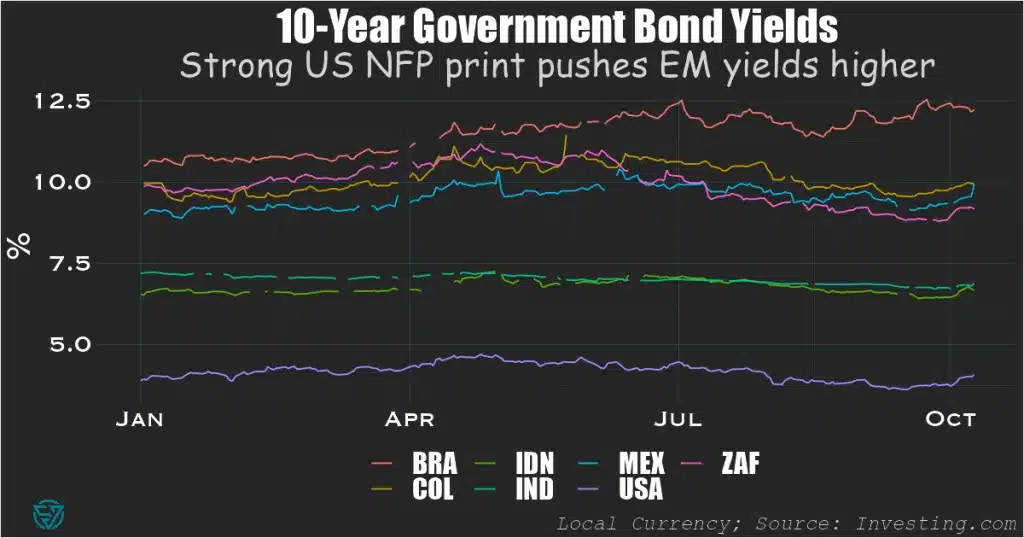

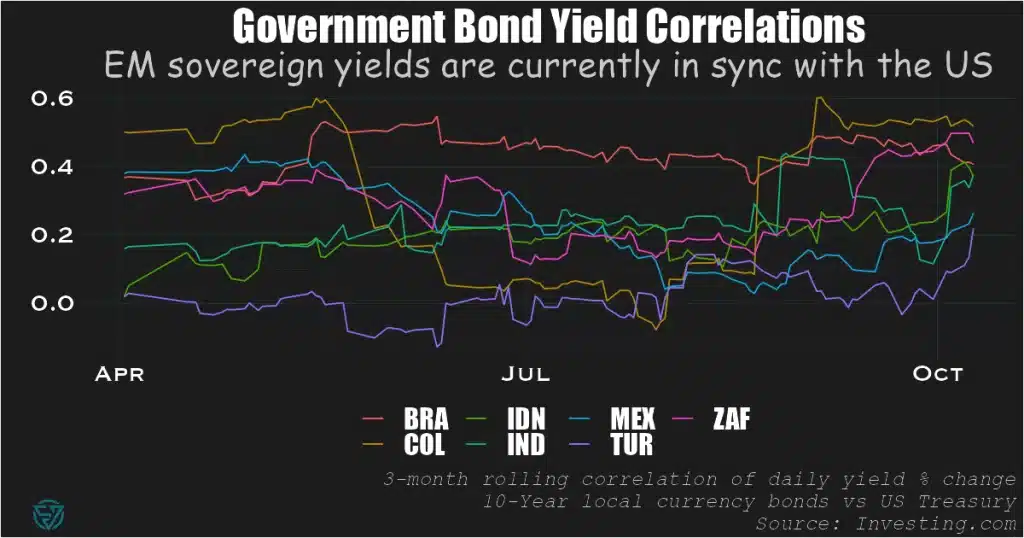

Fed rate-cutting

The conditions were supposed to be favorable to emerging markets.

The beginning of a Fed rate-cutting cycle is reliably a good omen for the EM universe.

Lower U.S. yields mean lower yields for EM debt, especially if it is dollar-denominated.

While lower borrowing rates for EMs assumes spreads remain somewhat steady when U.S. rates are lower, in any case the effect of lower U.S. rates helps drive capital flows towards EM.

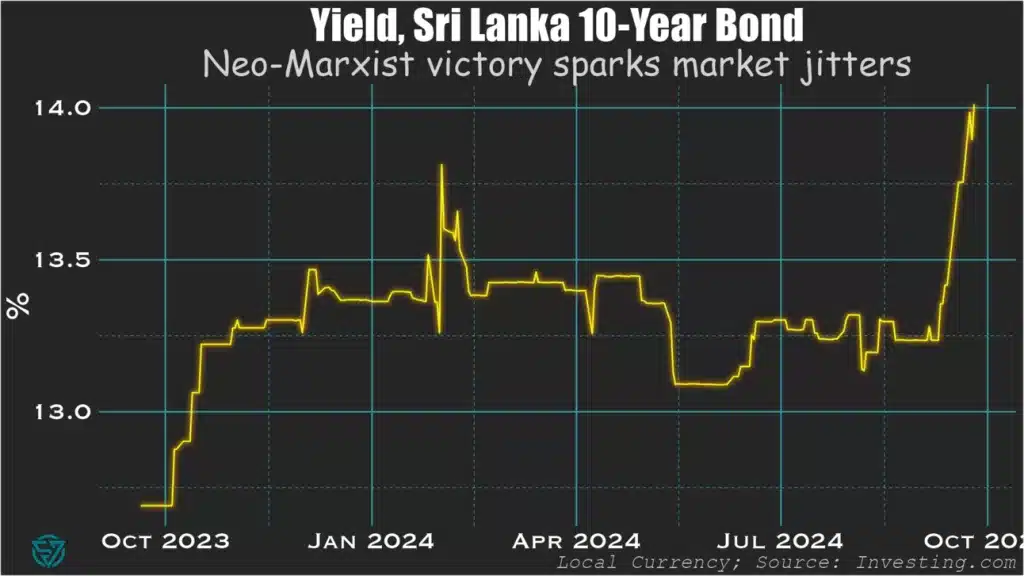

Trump trades in full swing

But Trump’s victory has just blown that narrative out of the water.

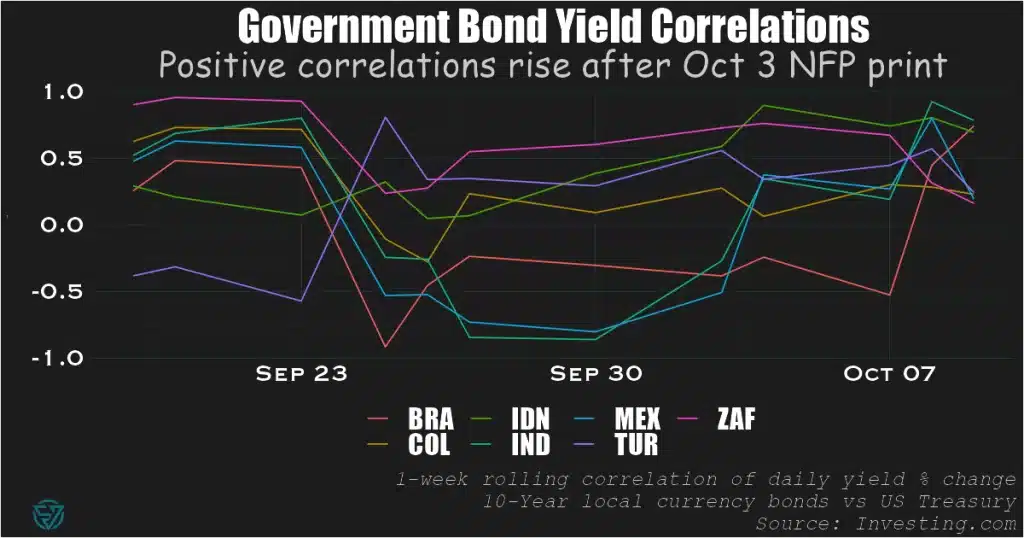

Sure, U.S. yields were already rising in October on the back of strong non-farm payroll data and robust economic growth, though this was tempered by weak jobs data late last week.

Yet the market reaction has pushed U.S. yields up further across the yield curve, in a bear steepening, which sees long-term rates rise fastest.

This means that markets expect increases in:

- nominal growth & inflation: as a result of lower taxes, higher spending and higher fiscal deficits.

- uncertainty: due to policy volatility, including on trade tariffs, hence the higher term premium at the longer end of the curve.

Meanwhile, other “Trump Trades” are in full swing: U.S. stocks, the USD, and Bitcoin are all up.

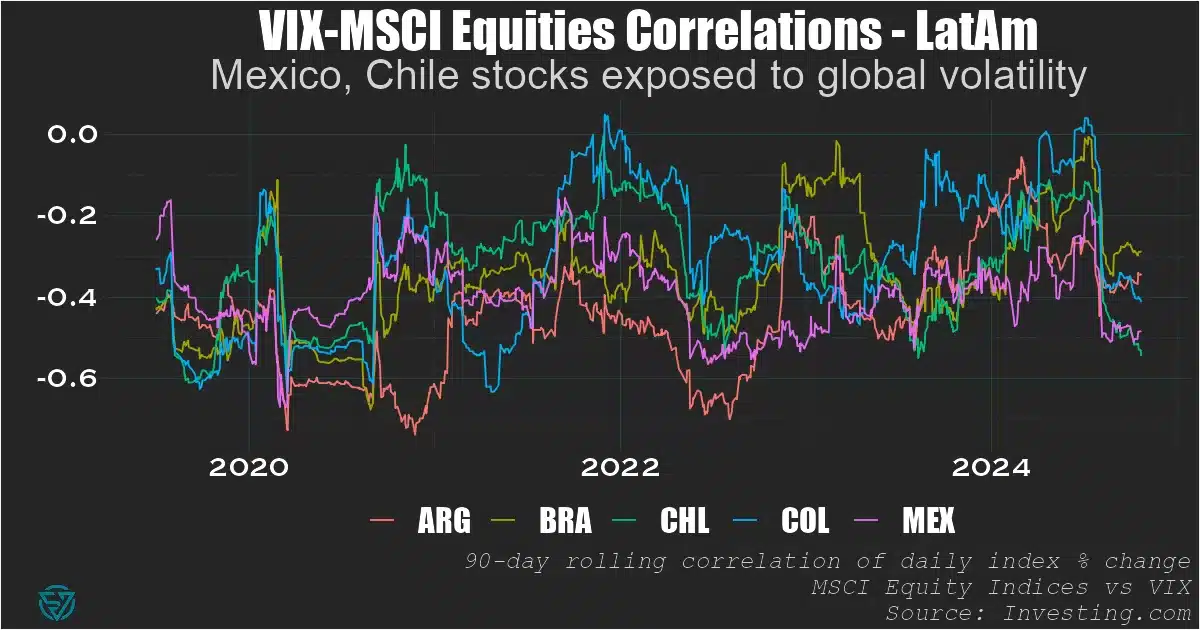

EM under pressure

In this new higher-U.S.-yield, stronger-USD environment, EM currencies have taken a battering in the immediate aftermath of the election result.

The broad EM currency index registered its largest daily loss since early 2023, with the Mexican peso and Eastern European currencies suffering.

Asian equities pulled down the MSCI EM equity index by 0.7% on November 6th, as market participants evaluated the impact of Trump’s tariff policies.

Hong Kong equities dropped by some 2.5%.